Reviewed:

Reviewed:

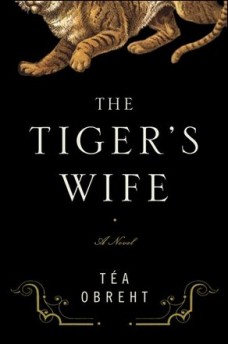

The Tiger’s Wife by Téa Obreht

Random House, 352 pp., $25.00

Fairy tales, according to the late, great psychoanalyst Bruno Bettelheim, soothe young readers’ confused minds by conveying that, although struggle is intrinsic to life, moral behavior inevitably ensures victory. Might the genre of adult fairy tales known as magic realism possess the same therapeutic potential for more mature readers? Not much is as perpetually bewildering and frightening as war, so it shouldn’t be any surprise that Téa Obreht’s The Tiger’s Wife, which uses familiar magical and folkloric devices to tell a story underpinned by the bloody history of the author’s Balkan homeland, has been so warmly received. Seasoned critics like the New York Times’ Michiko Kakutani and the Washington Post’s Ron Charles have delivered full-throated raves of this debut novel, whose author — no review has so far failed to mention — is just 25, and the youngest member of The New Yorker’s “20 Under 40” list.

Like many fairy tales, The Tiger’s Wife begins with a death. The deceased is the grandfather of narrator Natalia, a young doctor in an unnamed region that’s presumably Obreht’s native Serbia, in the years just after the war’s end. His death is not a shock — he was terminally ill — but the particular circumstances of his passing, in a dismal village across the newly enforced border, are mysterious. Natalia decides to solve the mystery at any peril but, characteristically for a novel straining at the seams with its author’s fecund imagination, she must juggle one heroic quest with another.

With her friend Zóra, a thinly drawn foil whose role is to smoke and be sassy, Natalia is on her way to administer vaccines to war orphans. It’s a mission of mercy but also diplomacy because, as Natalia points out, the children’s parents were killed “by our own soldiers.” Perhaps if she were also stopping off to train some seeing-eye dogs for the benefit of blinded enemy combatants, Natalia’s saintliness might be even better established, but as it is, she’s the unmistakable embodiment of goodness. She tells us halfway through the novel that pediatrics was her second choice, after helping “rape victims, women who were giving birth in basements while their husbands were walking through minefields.”

By the end of the first chapter, Natalia and Zóra have arrived at the home of the couple they’re staying with, and two suspenseful questions have been posed: why is a band of sick people digging up the couple’s vineyard, and why did the grandfather die in an obscure locale miles from home? Impatient readers will be somewhat dismayed at the many pages that elapse before we’re offered even a clue to either puzzle, because Natalia pulls back from the present to reminisce about her grandfather and relay two stories about his life, which offer, she promises, “everything necessary to understand” him. (We don’t learn his name; per Bettelheim, figures in fairy tales should be nameless, “thus facilitating projections and identifications.”)

The first of these narratives takes place when the grandfather is nine years old, and his village is besieged by terrifying rumors that an escaped tiger is roaming free. After attempts to track and kill the animal fail, and the wife-beating local butcher disappears, a legend is born that his pregnant widow — a deaf-mute teen whose only friend is the grandfather — has struck up an inter-species romance, becoming “the tiger’s wife.” The second reveals the grandfather’s bargain with a mystical figure known as the deathless man, the nephew and minion of Death himself. Connecting the novel’s various strands is a talismanic copy of The Jungle Book, carried by the grandfather all his life and required by Obreht to carry immense schematic and metaphoric weight.

Easily the most engrossing passages are in the deathless man sections; here’s the grandfather describing their first encounter:

He reaches round and fingers the bullets in the back of his head, and the whole time he is smiling at me rather like a cow. I can picture his fingers moving around on the bullets, and the whole time he is touching them I am reaching for his hands to stop him, and I can imagine his eyes moving around, in and out of his head, as the bullets push his brains out. Which, of course, isn’t happening. But you can see it all the same.

The sections involving the tiger’s wife suffer from endless digressions and lengthy backstories of minor characters. With the first appearance of a line like, “Luka was the town butcher, who owned the pasture and smokehouse on the edge of town,” my heart sank a little; by the time I was obliged to read six pages about how the apothecary found his calling, I was anticipating the novel’s conclusion with considerable eagerness. Part of the problem is that Obreht’s writing bears the stamp of the assiduous and gifted MFA student who’s been schooled in short story writing at the expense of learning how to pace a full-length novel: every single character and scene gets its lavish, minutiae-laden close-up, resulting in prose that’s hard to fault on the sentence level but fails to cohere as an irresistible reading experience.

The other problem with the proliferation of stories here is their invariable illustration of How To Be Good. Unlike a child reading Cinderella, I don’t look to fiction for moral guidance. On the contrary, moral murkiness is arguably what elevates literature above mere storytelling — the element that distinguishes a devastating masterpiece like Coetzee’s Disgrace from an enjoyable melodrama like Hosseini’s The Kite Runner.

Still, the appeal of parables — and The Tiger’s Wife is a veritable Russian doll of parables — is undeniable, and so is the enticing escapism offered by the fantastical mode. A. S. Byatt once said she reads Tolkien when she’s ill, because “there is an almost total absence of sexuality in his world, which is restful.” Similarly, readers of The Tiger’s Wife will barely be disturbed by depictions of adult relationships; the elderly, children, and animals are Obreht’s, and Natalia’s, focus. Even the dark forces of war and death that ostensibly propel the story are defanged, in true fairy tale fashion, by magic and folklore. And although the former Yugoslavia’s civil war is continually, albeit usually obliquely, referred to (“our side,” “your side,” “their side”), no real exploration of the reasons behind the tragedy emerges. It’s possible Obreht had no desire to spoil her readers’ cozy enjoyment with politics, but another possible explanation suggests itself: how could a book whose central message is the value of superstition, ritual, and myth reconcile that message with a lament for a conflict catalyzed, in its ethnic and religious clashes, by the same?

Emma Garman is a writer living in New York. She can be visited online here.

Mentioned in this review: