Reviewed:

Reviewed:

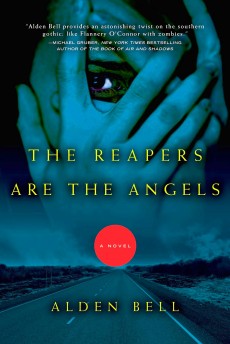

The Reapers Are the Angels by Alden Bell

Holt, 240 pp., $15.00

There is apparently a rule that anything one has to say about The Reapers Are the Angels, Alden Bell’s entry in the booming post-apocalypse zombie genre, must begin with an acknowledgment of the author’s debt to Cormac McCarthy’s The Road and pretty much all of Flannery O’Connor, so let’s get right to it: yep, y’all, they’re kinfolk, and Temple — Bell’s heroine — is their love child.

A lot of people have done the reserved masculinity in which McCarthy specializes. His men of few but freighted words are only a special case of a larger category of terse American men that includes David Mamet’s villains and just about every Southwestern hero that John Wayne, Gary Cooper or Clint Eastwood ever played. And how many authors have done to death poor, ignorant Southern girls who see beauty and love God? The special genius of Bell (also known as Joshua Gaylord, author of Hummingbirds) is to unite the two archetypes, and many more, in the skin of the most appealing teenage-girl-slayer-of-the-undead since Buffy’s first incarnation (Kristy Swanson, not Sarah Michelle Gellar.) McCarthy’s gnarled strength and O’Connor’s humble virtue are packed into the laconic Temple, who roams the South and Southwest dispatching the “meatskins” with a Gurkha knife, but never without grace and a calm respect for the former humanity of her adversaries.

Bell’s central concern is not zombies but a 21st-century extension of the most venerable continuously active theme in American literature: the end of the frontier. The popular culturewide yearning for the zombie apocalypse is rooted in the fruitlessness of dreaming in a world where we can have everything except something different, and be anything except original. We live at a time when the central concern of the young is the heartbreaking desire for authenticity, in a world in which instantaneous mass communication makes every way of being on Earth a commodity. The zombie apocalypse returns us to a world of possibility, in which what we are has consequences and ownership means nothing.

Bell clearly loves his people, and not just Temple, who everyone loves, but humans in general, even the semi-dead ones. He writes from a distinctly old-fashioned point of view. His characters may not be good, or deserving of love, but morality orders their lives. Even the implacably murderous Moses, who pursues Temple, like Javert, in the name of a twisted justice, does so for a reason. As Temple observes, “[Southern boys] just sit around waiting for somebody to kill their brother so they can get started on some vengeance.” And she has, in an act of self-defense, dispatched Moses’ brother, the loathsome Abraham.

When she thwarts Abraham’s attempt to rape her, his intentions progress to homicide, and she regretfully sends him into the void with no more ceremony than she would put down a zombie. “No more” is not none. Though injured and in pain, she pauses almost tenderly to make sure that Abraham’s brain is destroyed, in order to spare him reanimation. (Abraham’s bungled crime recalls the unforgettable “squeal like a pig” scene in James Dickey’s Deliverance in its explicit recognition of Abraham’s assault as a perversion of love, and only incidentally as a perversion of desire.)

The bloodiest stretch of the book, and the least successful, is an episode in which Bell steps outside the zombie canon and seems to channel H.P. Lovecraft. Temple encounters a clan of hillbillies whose old-fashioned family values have morphed, along with their bodies, into something monstrous. A Lovecraft fan might find its baroque tone less jarring, but I generally prefer my un-dead straight up.

One almost suspects a wry joke in Bell’s echo of McCarthy’s distinctive voice. Although McCarthy’s novels are filled with bad men and the men who struggle against them, they are ostentatiously devoid of moral content. When, rarely, his men are good (and there are almost no women), their goodness is more like a tribal affiliation. Their purposeless amorality is mythopoeic. Reapers, on the other hand, is about a woman, and there is almost nothing the living in it do that is not motivated either by the characters’ moral sense or its stepsister, the love of beauty. For a gore-soaked apocalyptic romp, the book has a decidedly 19th-century feel.

Peter Coates is an artist, programmer, and writer living in Brooklyn.

Mentioned in this review:

The Reapers Are the Angels

Hummingbirds

The Road

The Complete Stories of Flannery O’Connor