Reviewed:

Reviewed:

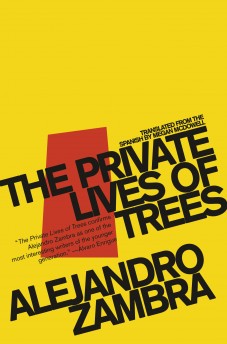

The Private Lives of Trees by Alejandro Zambra

Translated by Megan McDowell

Open Letter, 104 pp., $12.95

The promotional copy on the back cover of The Private Lives of Trees says the book “demands to be read in a single sitting,” but pay no attention. I read it over two nights and was just fine. And coming back to it days later, I leisurely let myself in wherever my thumb landed, enjoying the prose again without a care in the world. It’s rare to find a story—much less such a short one—that offers this kind of pleasure and manages to linger in mind as an unsolved mystery. (My previous happy experience in this vein was with the Russian classic Envy by Yuri Olesha, which will forever remain my template for the genre.)

A single sentence sums up the plot of Trees: A man named Julián puts his stepdaughter to sleep by telling her stories while waiting for his wife, Verónica, to come back from a drawing class. That’s all there is to it, a present tense occupied by waiting at night inside an apartment. There are no visitors, no natural disasters, no hidden crimes. The place is Santiago de Chile, but it wouldn’t take much to turn it into any other Latin American city.

As soon as Verónica returns, we are told early on, the novel will end. Or it will end as soon as Julián “is sure that she won’t return.” Death, that mother of all plot devices, looms large, but as the book progresses you get the feeling that it may not make a formal appearance. Zambra sets up a moment occupied by waiting, and then proceeds to pull your expectations out into the night. The real challenge is not resisting the urge to create a plot in your own mind but to simply abandon the need for resolution.

Framed by the story Julián tells his daughter–about a poplar tree and baobab tree, “who, at night, when no one can see them, talk about photosynthesis, squirrels, or the many advantages of being trees and not people or animals or, as they put it themselves, stupid hunks of cement”–the novella also flashes back to tell of Julián’s former romantic disappointments and the manner in which he met Verónica.

If postmodernist gestures give you pause, then the beginning of the second chapter might make you put the book down. That’s what I did when Julián’s occupation is disclosed: he’s a literature teacher and writer. The good news is that Zambra gets away with this self-referential move, just as he gets away with passages about writing the novel, some references to the imagination at work, and even a joke about Paul Auster’s technique. By the end of the chapter the writing feels easy and right, and the intellectual current that sustains the story, its postmodernist bent, never really threatens to drown the reader.

Zambra is a poet, and readily admits his lack of interest in stories that have intricate plots or complex characters. This brings to mind Álvaro Mutis, also a Colombian poet and novelist, whose Maqroll stories (published in English as The Adventures and Misadventures of Maqroll) breathe their own mysterious air. As with Mutis, Zambra’s aim seems not to subvert the conventions of realism, but to use those conventions sparingly, planting one foot in reality while holding the other foot up in the air, refusing to advance. Many of the book’s sections are divided by double spacing, and this also brings about a less linear quality, more in tune with the dozing effect that stories told at bedside tend to have.

In Trees, Julián and his stepdaughter wait, and the story spins around them, most of it powered by Julián’s imagination. Because the present refuses to resolve itself, the future sneaks in at some point, crisp and alive, and as exciting as the best daydream you ever had.

Juan Pablo Lombana is a Colombian writer living in New York. His first novel, Deudas de un patadura, was published last year by Alfaguara Colombia.

Mentioned in this review:

The Private Lives of Trees

Envy

The Adventures and Misadventures of Maqroll