Reviewed:

Reviewed:

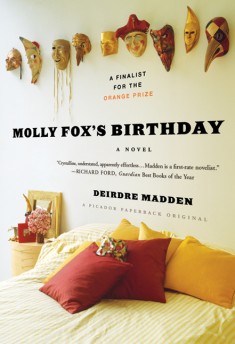

Molly Fox’s Birthday by Deirdre Madden

Picador, 240 pp., $14.00

Padding around her friend Molly’s apartment, the nameless narrator of Deirdre Madden’s novel wonders, “Who is Molly Fox?,” and goes about the rest of the book trying to decide. The question is unanswerable, of course, as it always has been: How does one know a person? How does one know oneself? The closest we can come is through representation: experience, objects, communication. It’s appropriate, then, that Molly Fox is an actor—a good one, “a medium who could summon up not those who were dead, but those who had never been anything but imagined.”

Like Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, Molly Fox is a performer, though a professional one. Mrs. Dalloway’s machinations for her party are largely performative—part of an identity she’s created since her marriage to Richard. In both novels, a run-in with an old friend causes our narrators to question their existence—seeing themselves for the first time from the inside out. Molly is the sun around which the narrator and her close friend Andrew revolve, like Mrs. Dalloway’s Sally and Peter. Here, Mrs. Dalloway is split in two—with Molly herself doing the performing and our narrator doing the introspection.

The influence of Woolf goes beyond the particulars of Molly Fox’s Birthday—a stroll to get flowers, the reemergence of old friends, the action taking place in one day—to its emotional tenor and writing style as well, emphasizing the power of memory and the small behaviors that make us who we are. The narrator is staying in Molly’s Dublin home while Molly appears in a show in New York, and the quiet house-sitting is meant to aid and abet work on writing a new play. But the narrator largely avoids work, instead recalling pivotal times in her friendship with Molly, like when she first saw her at university, in a production of The Importance of Being Earnest. After picking up a book in Molly’s library, which houses a few keepsakes of the production, the narrator remembers Molly’s hair, the way she stirred her coffee.

“Friendship is far more tragic than love,” she observes. “It lasts longer.” Though she emphasizes that her love for Andrew is only platonic, we know this is not the case, especially when she invokes the words of her favorite playwright, Oscar Wilde, about his lost love, Bosie: “How could I not love him? He ruined my life.” And though Andrew does physically appear at the end of the novel, it’s at Molly’s doorstep, thinking she’s home. It’s Molly he’s in love with, not the narrator, his dear old friend. At first she wants him to go away, as she’s finally had her inspiration for the play: “Yes, the subject had finally fallen open before me, like a chestnut in its case that splits to reveal the clean white lining, the glossy brown of the nut, after days of trying to pick open tightly sealed prickly green cases.”

But Andrew stays on, describing how an apartment he rented in Paris began to disturb him after a near-death experience. “There was an intimacy about all these things, but one that I couldn’t connect with because I didn’t know the people who owned them,” he says, “and that failure to connect was deeply unsettling.” What proves more unsettling for the narrator is the failure to connect with herself. Molly’s profession allows her the freedom to cry out, “I am Duchess of Malfi still,” reinforcing and inspiring her strength of self through a character, whereas the narrator keeps her emotions in check. As the narrator asks, “Is the self really such a fluid thing, something we invent as we go along, almost as a social reflex? Perhaps it is instead the truest thing about us, and it is the revelation of it that is the problem; that so much social interchange is inherently false, and real communication can only be achieved in ways that seem strange and artificial.” Only through art are we able communicate the most essential elements of who we are. Our narrator and Andrew are drawn to Molly because she is so capable of this kind of declaration.

This is a brilliant definition of art and of performance. Madden has written a novel with the flavors of Woolf’s classic, but distinctly her own and beautifully executed. She ends the book with another surprise visitor, reminding us that while we may change by following our curiosity or simply fighting against the ravages of time, the first step towards knowing oneself is to acknowledge that “the self” exists. As Peter exclaims upon this discovery at the end of Mrs. Dalloway, “It’s Clarissa! For there she was.”

Jessica Ferri is a writer living in Brooklyn working on her first book. You can visit her here and here.

Mentioned in this review: