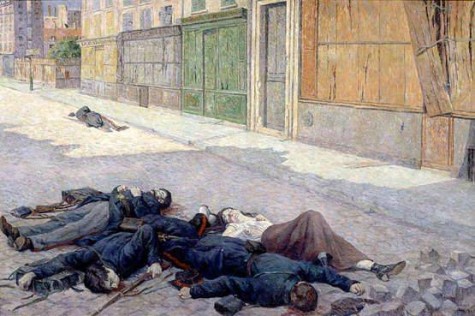

[Pictured above: A Paris Street in May, 1871 (La Commune) by Maximilien Luce]

Reviewed:

The Culture of Defeat: On Trauma, Mourning, and Recovery by Wolfgang Schivelbusch

Currently out of print

Symbolic images of defeat generally involve a fall of some kind. Remember the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue? The awkward and clumsy draping and subsequent removal of the American flag, the undignified resort to equipment overkill in pulling it from its pedestal, the slow and creaky decline, the amputated legs, the Lilliputian assault of bystanders with their shoes? There was a discouraging disparity between the effort to establish an iconic moment in history, which was surely stage-managed, and the utter banality of the actual event.

Another fallen statue illustrates the cover of The Culture of Defeat by German historian Wolfgang Schivelbusch. The Vendôme Column—toppled in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War by the Paris Commune of 1871—lies in rubble, a dreamy, sepia-toned Parisian landscape of water and arches in the background. Within a couple of months, the Communards would be brutally suppressed, and the mythology of a Lost Cause would start to take hold.

How do nations cope with defeat? While the victorious can enjoy a straightforward, confident embrace of triumph, losers face a complicated psychological and cultural process that is remarkably consistent across different time periods and in difference countries. This process is the subject of The Culture of Defeat, which examines the effect of military failure on national identity.

Schivelbusch focuses on a relatively brief but dynamic period of modern Western history: 1860 to 1918, a time of rapid industrial growth, the rise of mass societies, and warfare that moved from regional to global devastation. This imaginative and convincing work establishes common threads among the vanquished in three very different conflicts: the American Civil War, the Franco-Prussian War, and World War I. In each case, Schivelbusch explains the historical circumstances that primed a populace for war, the (always) unexpected and total defeat, and the stages of mourning and regeneration.

The American Civil War, modern history’s first total war, merits special attention. The starkly different cultural identities that distinguished the North from the South emerged from the earliest colonies. The stereotypes were of hardworking Puritans battling a harsh wilderness climate on the one hand, and cultivated gentlefolk enjoying an Arcadian paradise on the other. These differences were noted often enough, but coexisted without rancor well into the 19th century. Complicity in the slave trade had been general, as was a lively debate about the practice. It wasn’t until the 1830s, with the expansion of industrialization in the North, that the South took a defensive posture to offset the inevitability of its own demise.

In the decades before the outbreak of the war, the mythology that would propel the South to rebellion developed on multiple levels. Debate over slavery was suppressed. “Cavalier” became a preferred term for the Southern gentleman, which referred back to the English Civil War between Cavaliers and Roundheads, and provided a context for regional discord. As the abolition movement gained momentum, there was angry renunciation of a mercantile and hypocritical North. Educated men put forth elaborate defenses of slavery—it was preferable to the harsh working conditions in northern factories, rooted in the noble traditions of Ancient Greece, the best sort of “socialism,” etc.—which coalesced into a rigid, unsupportable philosophy of the “peculiar institution.” By the time the war began at Fort Sumter, the South was largely united by a frenzied, mass fantasy of rebellion that ultimately sent more than 20% of its white male population to their deaths. That so many of the best and brightest of our new nation could die for such muddled reasons is a vivid illustration of the power of myth in shaping and directing the actions of a people who feel threatened.

The total warfare of Generals Grant and Sherman was almost entirely prosecuted on Southern soil, exacting a devastating toll on military and civilian populations alike, and in the process uniting them in a common identity. (The disastrous Gettysburg Campaign all but determined the outcome of the war, but the South fought on, incurring even greater casualties as its prospects dimmed.) The casualty rate amongst white male Southerners was nearly triple that of the North, and property damage ran to several billions of dollars. Even after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox acknowledged ultimate defeat, it was with difficulty that he persuaded his generals to lay down their arms. C. Vann Woodward, in The Burden of Southern History, wrote that the (white) South “had to learn the un-American lesson of submission.”

Schivelbusch carefully charts the stages by which the South made its way from destruction and occupation to reconciliation with the North, and shows us how these stages were repeated in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War and World War I. Losers initially manage by entering what Schivelbusch refers to as Dreamland, in which they quickly move through shock and depression to a sort of elated “embrace of the new.” Distance is created from defeat by assigning blame, usually to the deposed leader. Thus freed from guilt, there comes the expectation of reinstatement to pre-war status. When this expectation is disappointed, the resulting sense of betrayal launches a complex mythology that involves converting military failure into cultural superiority: something fine was defeated by something ignoble; the victors resorted to dirty tactics; soldierly virtues were overwhelmed by sheer numbers, technical advantage, etc. The past is glorified, and symbols of martyrdom are revived through the arts: Sir Walter Scott’s fiction and the expanding myth of the Lost Cause in the South, the cult of Joan of Arc and The Song of Roland in France, the Nibelungen legend of Siegfried in Germany–the vanquished offset their humiliations by associating themselves with the heroic loss of legend.

The Dreamland stage, as it unfolded in the aftermath of the American Civil War, almost constituted a virtual reality. All of its components had been in place before the outbreak of the war, and in defeat they were readily summoned by a national psyche and dispensed like prosthetics to amputees. When Reconstruction made it evident that the South would not be restored, but had to instead be remade, the nostalgia of The Lost Cause, with its assumption of moral victory, took on a punishing aspect. The clan traditions of a common Scottish heritage had long been emulated in local Southern militias. Its struggle for independence, with its chivalric heroes, was appropriated by the Ku Klux Klan to validate a violent ideology of resistance.

The cold war of Reconstruction officially ended in 1877 with a mutual recognition of the benefits of economic expansion in the New South. Efforts were made to become a “better North” while retaining the old Southern culture, with the predictable result that codified racism remained intact, while modernization failed to thrive. The Lost Cause became the chief export of the South, a literary and theatrical explosion of plantation legends that became hugely popular in the North, and which imaginatively resolved conflict between the regions.

The conviction of the defeated, that they were overcome by unfair means, is not always false. The South, for instance, showed superior leadership, maneuverability, and fighting spirit until the North was able to unleash the wholesale destruction that eventually drove Old Dixie down. Emulating the victor comprises another stage in the psychology of defeat, but it invariably contains the secret goal of revenge and deferred victory.

Barely two months into the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, Napoleon III was captured with his entire army at Sedan. The French humiliation was offset by internal scapegoating, revolution, and renewed national fervor, which fueled the war for several more pointless months before capitulation, followed by civil war and the bloodbath of the Paris Commune. The harsh treaty imposed by Bismarck in January 1871, which included the annexation of Alsace and Lorraine, set in motion “La Revanche,” a mass delusion and unifying force that motivated the nationwide French urge for transformation.

“Never speak of it; think of it always.” The humiliation of Sedan took up residence in the collective spirit of the French. Victor Hugo made passionate claims that France was synonymous with “civilization.” A national conviction evolved, that a stronger France, rising from the ashes of defeat, would exact full revenge. Learning from its enemy’s military educational prowess, and exporting its own “superior” culture through colonial expansion, France successfully elevated its status as a nation in the decades leading up to World War I. In The Guns of August, the classic military history of the initial stage of that conflagration, Barbara Tuchman describes French strategy against Germany in a chapter titled “The Shadow of Sedan.”

Schivelbusch finally turns his attention to Weimar Germany after its surrender in 1918. Still deep in enemy territory, the German army was widely believed to have plenty of fight left. Its sudden submission was met with shock at home and a general, shaming sense that the army had prematurely surrendered. Left with no Lost Cause mythology, the Germans found consolation in the dubious belief that Germany remained “undefeated on the battlefield.” Blame was placed on “foreign” elements at home, in the form of “the stab in the back,” which found its roots in the mythology of Siegfried and the Nibelungen legend. Unwilling to accept military inferiority, Germany focused on the skill with which its conquerors had used propaganda to undermine its will to win. Copying the common forms of martyr propaganda helped the country through its Dreamland phase. Propaganda evolved as the prime method of reinventing a national identity, culminating in the atrociously effective use of it by Hitler and the Nazis.

Schivelbusch maintains a compelling tension between dismay at the sheer mountain of lies that losers embrace, and awe at the ability of a devastated people to regenerate at all. We recognize elements of this process from the experience of loss and recovery on an individual level. Joan Didion has referred to it as The Year of Magical Thinking. When defeat overwhelms whole nations, the exaggerated, irrational drama that animates the masses may offer protection from what is unbearable, but it can do real harm in the world. At the same time, the energies devoted to transformation are essentially creative, and can combine the old with the new in interesting and productive ways. Schivelbusch offers the fall of Troy as a prototype for defeat, and reminds us that Aeneas eventually took his place in mythology as the founder of Rome, while many of the Greek heroes of that conflict came to woe.

The Culture of Defeat was published in 2001, well before the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue. In a brief epilogue, Schivelbusch refers to the attack on the World Trade Center, the symbolic importance of the falling towers and the national need to respond. He invokes another symbolic image of defeat–the frantic 1973 rooftop evacuation of Vietnam by helicopter. He asks us to imagine this distance of three decades as an interim period, and wonders how it will shape our reaction to the events of 9/11. Seven years after our overthrow of Saddam Hussein, we may also wonder what combination of Dreamland/Revanche energies are being nurtured, and in whose hearts.

Lila Garnett is a photographer, photo consultant, and writer living in Brooklyn.

Mentioned in this review:

The Culture of Defeat

The Burden of Southern History

The Guns of August

The Year of Magical Thinking