Reviewed:

Reviewed:

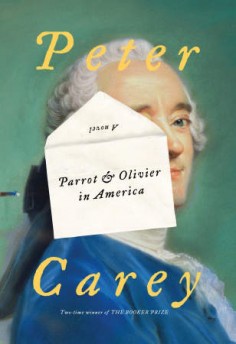

Parrot & Olivier in America by Peter Carey

Knopf, 400 pp., $26.95

People have been writing books about Alexis de Tocqueville and his famous treatise, Democracy in America, almost since the date of its publication. Now Peter Carey, the decorated Australian author who lives in New York, has added his own fictional take on the Frenchman’s life to the bibliography.

Parrot & Olivier in America, Carey’s beautifully written, if at times plodding novel, is about two Europeans and their journey to America. The first, Olivier, closely resembles de Tocqueville in his life and actions. The second, Olivier’s servant, Parrot, is a fantasy of Carey’s. Olivier, like de Tocqueville, is sent in the early 1830s to chronicle the sometimes revolutionary prison reforms that had been established in the United States. He is cajoled to go by his family, not coincidentally at a time of fomenting revolution—or re-revolution—in France. In short, he is running away.

But the novel, which purports to tell the story of the creation of Democracy in America, actually opens many years earlier, during the reign of the emperor Napoleon. At the start, Olivier is a young, whiny brat (he does not change much in this regard) who suffers through childhood in a sort of half-exile in provincial France. In crisp yet florid language—this is a Peter Carey novel, after all, and the language is often so vivid and fresh you want to strip off your clothes and swim in it—Olivier narrates what it was like to live a double life, to grow up watching his family quietly protest le petit caporal while at the same time serving him.

To give a sense of Carey’s considerable style, here is a passage from early on, when Olivier and his mother are traveling to Paris—it is Olivier’s first trip there—in the still receding wake of Napoleon’s first capitulation:

We were rocketed toward Paris, lifted upward, shaken sideways by the beastly Polignac springs, but in the midst of this turmoil my mother carefully filled one goblet and I witnessed my first soda bubbles, never guessing the gas had been gathered from the top of dirty brewery yeast, seeing only an ascension of my own spirit, fragile orbs of crystal rising in the golden light.

My mother and I drank and laughed and shrieked. Bubbles burst inside my nose, behind my eyes. We were, I swear it, drunk.

The often petulant and grasping, always entitled voice of Olivier shines through here, as it does in much of the rest of the novel. The Olivier chapters, as a whole, are fantastic. But the chapters of Parrot & Olivier in America alternate between the perspectives of the title characters, and while Olivier’s voice and story ring true, Parrot’s tale and tone are far-fetched and often cloying. What’s worse is that, by the end of the novel it seems clear which character Carey prefers, and it’s not the perfectly rendered aristocrat.

Parrot’s real name is John Larrit—called Parrot for both his red hair and his ability to mimic dialects. We first see him on an English road with his father, an itinerant printer. The two are soon set up in an illegitimate printing house. There, Parrot is made to crawl through a secret passage to an attic to deliver food to, and excavate the detritus of, an artist who is creating counterfeit money for the printing house’s owners, a stodgy old man and his mean-spirited French wife. This happy set of affairs is interrupted when a nobleman discovers the operation. It is likely they will be killed for their crimes. Everyone except Parrot, who runs away in the nick of time. The nobleman burns the house down with the artist still inside, trapped, it is assumed, in his tiny attic.

Decades later, through a series of events too tiresome to be even summarized here, Parrot has become Olivier’s servant. The two (finally) go to America together. Olivier’s chapters in America are wonderful, charting his slow recognition of the singularity of the American experience and his conflicting fear of and desire for it. When Parrot goes off on his own, the story quickly loses itself to the unbelievable.

Parrot has come to America with his French lover and her mother. The two women stay in New York while Parrot and Olivier scour the nation, first in search of prisons, then in search of love—the relationship between Olivier and Amelia, a Connecticut sweetheart, is one of the high points of the novel. Parrot leaves Olivier to return to his lover, and he finds that she has moved in to a house with—drumroll, please—the counterfeit artist last seen burning in the home of the English printing house all those decades ago. And the curmudgeonly wife of the printer is there, too, magically not so old (decades later) and not so curmudgeonly. How Parrot’s lover came to find and live with these two ghosts from his past, and how and why they happen to be in New York, is never adequately explained.

If Parrot’s tale sounds Dickensian, it is, but I have to think even Dickens would be embarrassed at some of these contrivances. And though it makes dramatic sense to narrate Olivier’s childhood, which helps explain his natural revulsion to democracy, the cumbersome childhood tale of Parrot only serves to underscore the utter implausibility of his character. Even with all of Parrot’s exhausting foibles, the gifted Carey has written a book with many pleasures. If it were half as long—and you know which half I would cut—the pleasures might be double.

Bezalel Stern is a writer and lawyer who lives in New York. He is currently working on his first novel.

Mentioned in this review: