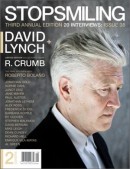

Stop Smiling, the Chicago-based culture magazine, recently switched gears to begin publishing books in partnership with Melville House. [Disclosure: I wrote a couple of pieces for Stop Smiling in 2008.] The imprint’s first book is How to Wreck a Nice Beach: The Vocoder from World War II to Hip-Hop by Dave Tompkins, a history of the Pentagon-created speech-scrambling device that went on to widespread use in pop music. (The title comes from a misinterpretation of a Vocoder-issued phrase: “how to recognize speech.”) I recently asked Stop Smiling publisher and editor J. C. Gabel a few questions about his new business:

Can you tell me a little bit about what spurred the transition from an eclectic culture magazine to a books imprint, and how you came to work with Melville House?

Can you tell me a little bit about what spurred the transition from an eclectic culture magazine to a books imprint, and how you came to work with Melville House?

While we worked on the magazine, we were always thinking about publishing books. We just never could find the time and opportunity. Several years ago, Kelly Burdick, now the Senior Editor at Melville House, contacted me about repackaging and republishing some long-form interviews from the magazine’s vast archives. The idea of a Stop Smiling Books imprint grew from there, but it took almost five years to come to fruition.

In 2008, it was clear to most of the staff of both Stop Smiling and Runner Collective (the design collective that art-directs our books, magazines, and web site) that independent print media, in general, was in trouble, and we would have to change gears in order to continue publishing. In some ways, we grew too large: As an independent full-color bimonthly magazine, we always struggled to carve out the right niche for our audience and advertisers while at the same time keeping costs under control.

With the advent of the Kindle and now the iPad, it wasn’t hard to see the writing on the wall: print magazines, in all their excess and wastefulness, were going to become extinct. Of course there were other, more practical developments, too, like the United States Postal Service eliminating the form of bulk mail we used to distribute copies inexpensively to subscribers, or the fact that advertisers started to pour their money and support into online initiatives and sponsored signature events. These factors were things outside our control. Eventually, books just seemed to make more sense on every level. Beyond that, we are all print junkies and wanted to continue publishing a product that people would save and collect.

Your first book, How to Wreck a Nice Beach, is a history of the vocoder, the speech scrambling machine originally created for military purposes and now ubiquitous in pop music. How did you find the book, and what makes it the right one to launch your imprint?

The vocoder book was grandfathered in as the first Stop Smiling book. James Hughes, my good friend, co-publisher and editor at Stop Smiling, had been working one-on-one with the author, Dave Tompkins, on this project for more than eight years. Over the years, this bugged-out mystique developed around it. (This lore has been tastefully singled out in several early reviews of the book.) [Ed. note: In his review of the book for New York, Sam Anderson wrote: “How to Wreck a Nice Beach is much more than a labor of love: It’s an intergalactic vision quest fueled by several thousand gallons of high-octane spiritual-intellectual lust. Outside of, say, William Vollmann, it’s hard to think of an author so ravished by his subject.”]

What eventually became How to Wreck a Nice Beach was originally going to be published by Broken Wrist Project, a small press James was running with mutual friends in Los Angeles. But as Dave and James accumulated more artwork and the word count continued to mount, it grew beyond something that Broken Wrist Project could reasonably execute. When we partnered with Melville House to launch Stop Smiling Books, we were able to take advantage of the shared costs of production, and we also benefited from Melville House’s partnership with Random House, which oversees their distribution. So, like some of our favorite themed issues of the magazine, a certain amount of serendipity played a role in the end result.

How many future releases do you already have planned? Can you tell us a little bit about a few of them? And do you have an idea of how many books you’ll be publishing annually?

How many future releases do you already have planned? Can you tell us a little bit about a few of them? And do you have an idea of how many books you’ll be publishing annually?

It looks as if we’ll be releasing two to three titles a year, including at least one original title and one repackaged collection. We have seven or eight books we’re currently working on through 2012. Originally, we envisioned a multi-volume collection of long-form interview books by subject (conversations with film directors, authors, and musicians) in the tradition of The Paris Review or Playboy collections. These three repackaged books will be among our first releases, starting with the directors installment, which will be out early next year. Each volume will also include a few book-exclusive interviews we never had the chance to run in the print magazine during its 15-year run.

In the pipeline, besides the three interview books, is a collection of interviews with Ray Bradbury, Listen to the Echoes by Bradbury biographer/scholar Sam Weller; the book companion to Thom Andersen’s video essay Los Angeles Plays Itself; and what was supposed to be the last issue of the print magazine (an issue devoted to Stanley Kubrick) will be adapted into a book of some form.

In what ways do you think the spirit of Stop Smiling the magazine will influence Stop Smiling the book publisher?

We’re still operating with the same mentality on the editorial front, but have adopted a Less Is More mindset — and a production schedule to match. It does feel nice to know that what we spend months or years working on is now being released in a permanent format. We’re really trying to reinvent the DIY aesthetic of the magazine to apply it to editing, publishing, and promoting books. The book-making process itself, of course, is much slower and drawn out, which is refreshing as we all get older.

What excites you most — and what scares you most — about starting a books imprint in 2010?

What excites us the most is working with and publishing work by some of our most talented friends. What scares us? The possibility that the majority of readers worldwide will one day stop buying physical books.