Reviewed:

Reviewed:

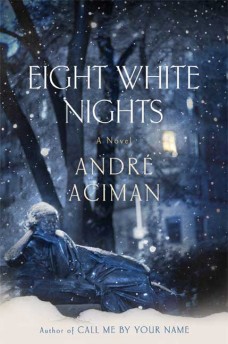

Eight White Nights by André Aciman

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 368 pp., $26.00

The unnamed narrator of André Aciman’s second novel, Eight White Nights, meets a woman named Clara at a ritzy Christmas Eve party on the Upper West Side and spends the rest of the evening hyperventilating. In prose.

Soon after she appears, Clara’s eyebrows are compared to the “rough plumage” of “tiny birds” and her social tricks to those of a “feral cat.” Later the same night, she’s likened to “a strange wildcat that licks your face to hold you down as she devours your insides,” her smile to that of “a very young lawyer who is about to enter a boardroom and is suddenly told by her secretary that her mother is on the phone.” Our narrator (or our author) is in such a tizzy that he can barely blink without sharing a metaphor for blinking. By the time the first of the book’s eight nights are finished, 90 pages in, Clara has been mummified in figurative language. The fact that this might accurately reflect the narrator’s desire to turn her into something other than what she actually is doesn’t greatly improve the experience of trudging through his initial astonishment.

Aciman is often successful in capturing something that is off-putting, especially a certain kind of paralyzing emotional attraction. As they spend the next several days circling each other, Clara and the narrator are by turns cowardly and brazen; confused and confusing; withholding and lacerating. They might even remind you of people whom you’ve loved. But the charm of examining their courtship at such length—whether they will ever properly kiss, much less sleep together, forms the novel’s titanic psychological struggle and the entirety of its plot—is highly dependent on whether or not you find them compellingly damaged or insufferably solipsistic.

From the moment they meet, Clara and her new admirer have a rare and thrilling—if highly self-conscious—rapport. They consecrate their flirtation with a steady flow of nicknames and inside jokes and the kind of showy self-flagellation (“We’re a mess, aren’t we?”) that is really thinly disguised self-flattery. With Clara, he’s reminded of “how easy it was to create a small world of our own together, with its own lingo, inflections, and humor. Another day together and we’d add five new words to our vocabulary. In ten days we wouldn’t be speaking English any longer.” This clubhouse feeling is undeniably attractive if you’re inside it, but reading about it can be a chore. The pair’s goofier moments are just that, and Clara isn’t half as clever as her smitten suitor believes she is.

There is fleeting grief in the distant background here, involving the deaths of parents, but such substantive psychological issues are rarely addressed, passed over for a gauzier brand of neuroses. The would-be lovers are well-heeled and right-thinking. They talk easily of Beethoven and Bach. They organize their week around an Eric Rohmer film festival. They never talk about jobs, if they have them. He (only 28 years old, which stretches credulity) sees a search light scanning the sky around a terrace and thinks: “[it] looped above us like a slim and trellised Roman corvus missing its landing each time it tried to come down on a Carthaginian ghost ship.”

Despite these obstacles in the reader’s way—the ceaseless metaphorical churning, the borderline unlikable characters, a general tone of she-knows-that-I-know-that-she-knows—the novel eventually offers a reward or two for the (very) patient. The narrator asks Clara, looking out across the Hudson from the party: “One could dream of a relationship and one could be in one, but one can’t be the dreamer and the lover at the same time. Or can one, Clara?”

No, one can’t, and Aciman’s real concern is the pair’s delicate encasement, so quickly developed, and the possible damage that might be done to it if they actually collide. Or if they don’t. The novel’s central subject is longing, and how its unrealized pleasures can often feel like our only authentic satisfaction.

The brief time the couple shares is enough to allow the narrator a revelation: “all along, a small unseen, untapped part of me was perfectly willing to suspect, as though for good measure, that I could just as easily have preferred the spell more than the person who cast it, the coded sparring between us more than the person I was sparring with, the me-because-of-Clara more than Clara herself.” Later he thinks of Clara’s most recent ex alone somewhere, his own heartbreak “the awful proof that being similar, and thinking the same thoughts, and feeling inseparable from someone was nothing more than one of the many screens that loneliness projects on the four walls of our lives.” It’s in these moments that Aciman eases off the effects and his novel achieves an uncluttered strength.

Eight White Nights derives its title and, roughly, its structure from Dostoevsky’s “White Nights,” about a man who meets and falls in love with a woman who’s pining for someone else. It’s a powerful story. It’s also, in the edition I own, 50 pages long. Aciman has written of his respect for Proust, Dostoevsky, and other masters, and his prose does hew to a classical rhythm. But the poet in him often runs wild, and it’s tantalizing to imagine what more he could make with less.

John Williams is the editor of The Second Pass.

Mentioned in this review: