Reviewed:

Reviewed:

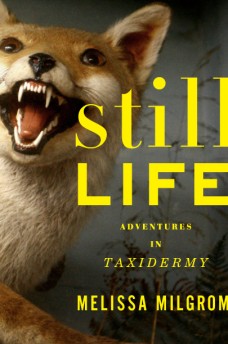

Still Life: Adventures in Taxidermy by Melissa Milgrom

Houghton Mifflin, 304 pp., $25.00

If you are the kind of reader who thinks Susan Orlean’s smart, offbeat pieces in The New Yorker about chickens, pigeons, or, well, taxidermy, are the best thing going in nonfiction, then Still Life is the book for you. Melissa Milgrom doesn’t offer a personal introduction or an explanation of the genesis of her idea—she simply jaunts off in search of working taxidermists and hopes we’ll follow her down this neglected path.

It turns out taxidermy isn’t at all what most people think it is: stuffing animals. No, taxidermy consists of maintaining only the skin of the dead animal and building everything else, its skeleton and structure, from scratch. Once the mannequin is made, the skin is stretched and made to fit, and details like fur color, eyes, and facial expression are painstakingly applied. The ultimate goal is not creativity but realism: restoring the animal as close to life as possible.

Milgrom opens with father and son David and Bruce Schwendeman’s taxidermy studio in Milltown, New Jersey. David, now retired, was the last chief taxidermist ever employed by the American Museum of Natural History. As David and Bruce explain, the majority of the industry is now built on the bragging rights of hunters, whereas the skill was once mainly used for museum dioramas. Taxidermists themselves, according to Milgrom, are “from blue-collar families” and consider themselves “outdoorsmen and hunters . . . in the spirit of Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett.” She follows these men and women to the 2008 World Taxidermy Championships in Springfield, Illinois, where she meets Ken Walker, famous not only for his work at the Smithsonian, but also for his spot-on Roy Orbison karaoke. Walker was at the WTC with a forged panda he made from the skins of black and brown bears—half of whose fur was still in the “blond phase.”

The most compelling parts of Still Life have everything to do with living people. Carl Akeley, born in 1864, comes closest to being a hero of the craft. The Museum of Natural History sent Akeley to Africa in 1925 to gather specimens for its African Hall. Akeley, at the age of 61, took his new wife, Mary Jobe, with him. In terrible living conditions, he fell ill, and died on Mount Mikeno. His team and his wife buried him in the lava rock. Akeley didn’t live to see the African Hall’s completion. It was named after him, instead of Teddy Roosevelt, as originally planned.

These stories of intense (sometimes bizarre) commitment to science are nicely juxtaposed with Milgrom’s portrait of Emily Mayer, taxidermist for conceptual artist Damien Hirst. Mayer is a short-haired, chain-smoking battle-axe who finds beauty in death. She’s absolutely essential to Hirst’s work, which features wholly preserved sharks, cross sections of pigs, and crucified cows. As Hirst says, Mayer is the only one who can “make it real.” When she was elected the chairperson of the Taxidermy Guild in England, Mayer balked at the term “chairwoman,” preferring instead “chairperson,” or “chairbitch,” as she stated in her acceptance speech. The role of taxidermy in contemporary art and culture is the book’s most fascinating section, so it’s something of a letdown when Milgrom turns her attention to the crotchety members of the Guild.

After a trip to Jamaica Inn (Daphne du Maurier’s Jamaica Inn) for the auction of Mr. Potter’s Cabinet of Curiosities, a Victorian collection of the weird and whimsical of taxidermy, the book loses steam. In a necessary chapter, Milgrom gets her hands dirty with her first project, a gray squirrel, which she enters in a competition alongside Mayer, who submits a pack of rats. Both lose to Walker, who astounds everyone with his rendition of the massive, long-extinct Irish Elk. Milgrom ends by comparing taxidermy to karaoke, in that a job well done is bringing someone (or something) back to life. The eccentric characters and random trivia in Still Life make it a delightful read. But Milgrom relies heavily on an inherent fascination with strange subcultures, never really convincing us of a larger reason to care about taxidermy or the possible deeper meanings of “making it real.”

Jessica Ferri is a writer living in Brooklyn working on her first book. You can visit her here and here.

Mentioned in this review: