Reviewed:

Reviewed:

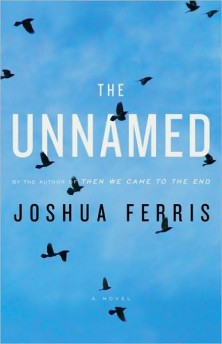

The Unnamed by Joshua Ferris

Reagan Arthur, 320 pp., $24.99

Tim Farnsworth, the tortured protagonist of Joshua Ferris’ second novel, The Unnamed, suffers from “a disease of one,” a mysterious, intermittent ailment that forces him to walk great distances without stopping. When they arrive, as suddenly and terrifyingly as seizures, the journeys take him far from his home or office, and all he can do is continue walking until the body’s demands cease as quickly as they began and he feels “arguably the most pleasurable physical experience of his life, to arrive at the end and, without giving a damn where, to lie down, the blood in his veins still walking, and to yield to the exhaustion.” Tim’s wife of 20 years, Jane, picks him up three or four times a week from his far-flung resting places: woods, park benches, a hair salon in the lower Bronx. His teenage daughter, Becka, views him as an alien, just with more reason than the average teenager: “[She] still thought her dad was mental. She didn’t want to think of it that way but who ever heard of what he had? Not even the Internet.”

At home, the family manages, albeit temporarily and with extreme measures: Tim is sometimes handcuffed to the bed to be kept from roaming. For a while, he holds on to his job at a prestigious New York law firm. It’s unclear at the start whether Tim is, as Becka thinks, “mental.” He certainly gets there over time, but it’s hard to tell if his psychological decline is a cause or result of his condition. (Doctors are at a loss to help him, so Tim’s hope becomes as worn out as his legs.)

Over the course of its first 200 pages, The Unnamed is a disappointing follow-up to Then We Came to the End, Ferris’ debut novel, which was met with equally generous (and well-deserved) amounts of popular and critical success. In that book, Ferris wrote with verve, humor, and control about a group of employees suffering layoffs at an advertising agency, and did so in a risky but perfectly executed first-person plural voice. (“We were fractious and overpaid. Our mornings lacked promise.”)

Then We Came to the End managed to be both profound and funny, but humor has gone missing almost entirely in The Unnamed. Here we are in the well-trodden world of vague upper-middle-class malaise: “[Jane] was startled by the complacency of the lotions, soaps, creams and deodorants arrayed on their bathroom sink, suddenly insulted by the rosy promises of common beauty products.”

The book rings with echoes of biblical imagery: thousands of dead bees inexplicably underfoot in a small New York City park, a flock of blackbirds falling out of the sky, the sudden appearance of wild boars. Fires. A flood. But for all of this portent, all of this Meaning, the majority of the book is as driftless as Tim on his long walks. It suffers from ungainly similes (“Angry tears came from her eyes like stubborn nails jerked out of brickwork”), pat psychology (“I used work as my excuse to avoid you”), and the bland banter of family TV dramas:

“We don’t need the money,” she said.

“But you enjoy your work. You’ve made a life for yourself these past couple of years.”

“You’ll find this hard to believe,” she said, “but you and Becka, you are my life.”

[. . .]

“Why would I find that hard to believe?”

“Because your life is your work.”

“Is that what you think?”

It wouldn’t be fair to cite awkward and generic moments like those if their tone didn’t accurately reflect long early stretches of the novel.

Fans of Then We Came to the End might spend much of The Unnamed thinking that Ferris is too talented not to rally, and he is. More than two-thirds of the way through the novel is an expertly rendered, heartbreaking scene in which we initially think Tim is back in his office. He’s not. From there, Ferris seems, for the most part, transformed, as if he’s finally reached the part he needed to write. The novel gains momentum and emotional resonance, and the writing turns richer:

He heard the blood pump out of his chest and flow down his veins to pulse faintly at his wrist and in the hollow beside his anklebone, and his breathing lifted him up and down, up and down, and he heard the calmness, like the coals of a settled fire, of his rested bones.

When Tim’s sanity cracks, he carries on conversations with himself—bitterly referring to the half that presumably causes the walks as “you”—about spirit vs. materialism, God vs. pharmacology. These thoughts on body and soul aren’t very advanced, but they yield to touching scenes in which Tim and Jane reach out to each other from increasingly great distances. One gets the sense that Ferris means for his book’s symbols, especially Tim’s disease, to carry various weights—like the “Airborne Toxic Event” in Don DeLillo’s White Noise, a novel for which Ferris has expressed admiration—but he is most effective when he is most literal, when the marriage at the book’s center is the focus.

During Tim’s final, epic march—it takes him as far as Missouri, and sometimes reads like Cormac McCarthy narrating Forrest Gump’s cross-country run (which I somehow mean in a good way)—Ferris hits the confident stride of his debut. It’s a finish that rewards those who make it that far, and that rekindles the promise that made this novel one of the most anticipated of the new year.

John Williams is the editor of The Second Pass.

Mentioned in this review:

The Unnamed

Then We Came to the End

White Noise