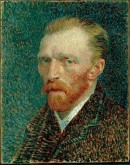

To wrap up Letters Week, I draw your attention to an incredible project: the online, searchable archive of all of Vincent van Gogh’s letters. The complete correspondence was recently published in a deluxe edition with a neat list price of $600. (At six volumes illustrated with 2,000 works of art, it seems fair, especially at the discounted price

To wrap up Letters Week, I draw your attention to an incredible project: the online, searchable archive of all of Vincent van Gogh’s letters. The complete correspondence was recently published in a deluxe edition with a neat list price of $600. (At six volumes illustrated with 2,000 works of art, it seems fair, especially at the discounted price of $480; there’s another complete, less lavish version available for just $63

.) The letter excerpted below, written to his brother Theo on October 2, 1884, came to my attention in Julian Bell’s review of the new set, and Bell explains the context for it: “[Vincent] has been carrying on with a vulnerable young village woman, to the disgust of his parents, and now she’s tried—not quite successfully, thank God—to poison herself. Theo has written from Paris, upbraiding him. Vincent’s rejoinder to his brother—vehement, outrageous and magnificent—ends up with nine postscripts, and this is from the seventh”:

Now there are people who say to me, ‘what were you doing getting involved with her?’—that’s one fact. Now there are people who say to her, ‘what were you doing getting involved with him?’—that’s a second fact. Apart from that, both she and I have sorrow enough and trouble enough—but regret—neither of us. [ . . . ]

Oh—I’m no friend of present-day Christianity, even though the founder was sublime—I’ve seen through present-day Christianity only too well. It mesmerized me, that icy coldness in my youth—but I’ve had my revenge since then. How? By worshipping the love that they—the theologians—call sin, by respecting a whore etc., and not many would-be respectable, religious ladies. [ . . . ]

I tell you, if one wants to be active, one mustn’t be afraid to do something wrong sometimes, not afraid to lapse into some mistakes. To be good—many people think that they’ll achieve it by doing no harm—and that’s a lie, and you said yourself in the past that it was a lie. That leads to stagnation, to mediocrity. Just slap something on it when you see a blank canvas staring at you with a sort of imbecility.

You don’t know how paralyzing it is, that stare from a blank canvas that says to the painter you can’t do anything. The canvas has an idiotic stare, and mesmerizes some painters so that they turn into idiots themselves.

Many painters are afraid of the blank canvas, but the blank canvas is afraid of the truly passionate painter who dares—and who has once broken the spell of ‘you can’t’.

Life itself likewise always turns towards one an infinitely meaningless, discouraging, dispiriting blank side on which there is nothing, any more than on a blank canvas.

But however meaningless and vain, however dead life appears, the man of faith, of energy, of warmth, and who knows something, doesn’t let himself be fobbed off like that. He steps in and does something, and hangs on to that, in short, breaks, ‘violates’—they say.

Let them talk, those cold theologians.