Reviewed:

Reviewed:

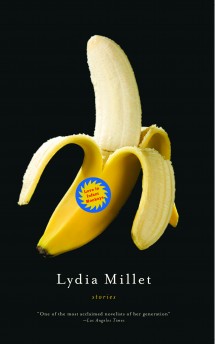

Love in Infant Monkeys: Stories by Lydia Millet

Soft Skull Press, 192 pp., $13.95

At first glance — “When a bird landed on her foot the pop star was surprised” — you might think Love in Infant Monkeys is little more than a light collection of odd exercises about celebrities and pheasants, celebrities and dogs, and elephants, and monkeys and so on. But keep reading and you’ll find in these immensely entertaining, and often poignant, stories, the subtleties and complexities of a long novel.

Each of these ten stories matches at least one animal and a human: Madonna and pheasant, Jimmy Carter and rabbit, Edison and elephant. . . Many of the animals are dead. Several of the humans are famous, and all of them are missing something, a fundamental communion they’re not getting from other humans. Animals in Millet’s world seem to think more than the humans, who, for all their superior intelligence, have little insight about themselves.

In Millet’s novel How the Dead Dream, the first book in her trilogy about extinction, T., the main character, thinks:

Animals were self-contained and people seemed to hold this against them. Possibly because most of them had come to believe that animals should be like servants or children. Either they should work for men, suffer under a burden, or they should entertain them.

T. never quite fits in with people and eventually finds himself searching among animals for bonds he’s long known don’t exist among humans. Likewise, when, in “Sexing the Pheasant,” Madonna says to to the pheasant she’s just shot, “I love you now,” we know she’s really talking to herself. There’s simply no one in she can talk to because she’s “the most famous person in the world, basically.”

The story “Girl and Giraffe” stars George Adamson, known to baby boomers from the movie Born Free, about his experience, with his wife, of raising a lion to adulthood and releasing it into the wild. At the time the story takes place, those days are gone and George lives alone with his “final” lions at a camp in Kora, Kenya. George is visited at his compound by a German who has made a pilgrimage to see him. The tourist is disappointed when George doesn’t live up to his vision of the valiant “Father of the Lions.” He mistakes George’s reflectiveness for the effects of alcohol, when finally George tells a story that may be the very culmination of his lifetime living with animals. The story is about a lion and a giraffe who seem to have come to an understanding before one kills the other:

It was almost, said Adamson, as though the possibilities of the world had streamed through Girl and the giraffe: And he, a hunched-over primate in the bushes, had been the dumb one, with his insistent frustrations at that which he could not easily fathom, his restless, churning efforts to achieve knowledge. Being a primate, he watched, being a primate, he was separate forever. The two of them opened up beyond all he knew of their natures, suspended. They were fluid in time and space, and between them flowed the utter acceptance of both their deaths.

What Millet is trying to tell us is not as black and white as the man-vs.-animal divide here suggests. The finest of these stories are enigmatic and evoke a loss that is nearly imperceptible to the characters, leaving the reader with a sense of not quite knowing what just happened. The final story, “Walking Bird,” represents the book well. A brief, parable-like story (it first appeared in the journal Fairy Tale Review), it concerns a family’s visit to an aviary. As they leave the zoo, the birds seem to have disappeared and the human visitors “making their way to the turnstiles, were all walking with a slight limp, an unevenness.”

Though their thematic and philosophical underpinnings make the stories in Love in Infant Monkeys a unified whole, there’s something lost in reading them all together. The writing is so evenly modulated that, despite its inventiveness, the collection suffers from a rhythmic uniformity. Sentence by sentence, the tone remains the same, and the stories even take roughly the same amount of time to read. Millet’s style is something akin to a classically trained musician playing jazz, where one wants her improvisations to feel more, well, improvised.

Still, Love in Infant Monkeys works so well on a philosophical plane that one accepts the tight modulation as a style meant to serve ideas that might otherwise be obscured, like, for instance, the work of Albert Camus, who will always be remembered for what he said rather than how he said it. It’s a safe bet that if this is your first reading of Millet’s work, it won’t be your last. (This is her seventh book.) She touches nerves that others don’t approach and uniquely perceives a civilization potentially as endangered as some of the species she writes about.

Bud Parr is the president of Sonnet Media LLC, a Web design and development company. He runs a literary blog called Chekhov’s Mistress and is the editor of the blog at Words Without Borders. He is on the advisory board for the Americas Series at Texas Tech University Press, which publishes contemporary fiction and nonfiction in translation.

Mentioned in this review: