Reviewed:

Reviewed:

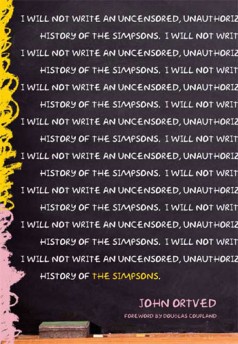

The Simpsons: An Uncensored, Unauthorized History by John Ortved

Faber & Faber, 352 pp., $27.00

Disclaimer: Like many people born in 1974, I’m incapable of writing a purely objective review of anything related to The Simpsons. The 1990s may have been a decade of peace and prosperity in the U.S., but it left much to be desired on the pop-culture front. The 1960s had the British Invasion, the 1970s had the golden age of American film, the 1980s even had its goofy-but-inimitable mix of MTV, early Letterman, and John Hughes movies. By comparison, Soundgarden and Singles seemed like a raw deal. But my generation in its youth had The Simpsons in its youth, and more than just the best thing ever made for TV (Homer’s clan was practically redeeming the existence of the entire medium when The Wire was but a twinkle in David Simon’s eye), the show’s glory days look more and more like the last gasp of eloquent mischief.

John Ortved, whose unauthorized oral history of the show may be flawed but is still an essential resource for any fan, establishes his credentials by focusing on the first eight seasons. (“If you’re really interested in what was going on in season 16, go on the Internet.”) It’s generally accepted among the show’s most ardent followers that these were the years when, as staff writer Josh Weinstein puts it, the show was “a great comedy lab, where you could try and do anything and no one would stop you, as long as it was good or funny.”

In the late 1970s, Matt Groening moved to Los Angeles and began drawing Life in Hell, the brilliant comic strip starring “a wordy, deeply cynical one-eared rabbit named Binky, his illegitimate son Bongo, and a gay couple — who may or may not be identical twins — named Jeff and Akbar.” Ortved didn’t speak to Groening (or to several other key people, more on which later), but he draws from outside sources to portray him as a spirited contrarian. In elementary school, Groening wrote: “The Boy Scouts are alright if you don’t have much to do, or you like to pretend to be in the army, and you enjoy saluting the flag a lot.” But he also mocked Evergreen College’s “countercultural piety” as the head of its student newspaper.

If Groening’s equal-opportunity satirical impulse has been embedded in The Simpsons from the beginning, those who spoke to Ortved question the extent of his overall influence. He undeniably created the family (modeled on his own) that made its debut as interstitial animated shorts on The Tracey Ullman Show, but as the show grew into a full-length hit, its visual style and verbal tone just as undeniably matured. The voices here are nearly unanimous that the maturation — the things we now think of when we think of The Simpsons — was more the work of Sam Simon, a veteran writer and producer who ran the show until leaving in 1993. (As with any oral history, it’s advisable to cross-examine the participants in your head while reading; the most full-throated dismissals of Groening come from people who worked closely with Simon. Ortved says early on that The Simpsons is a subject “contentious, bitchy, and riddled with vendettas.”)

One finishes the book sensing that Groening’s role in the show’s development and success certainly requires perspective, but that the “unauthorized” nature of things also privileged the views of the underappreciated. For the record, Groening has said elsewhere, “I think Sam Simon is brilliantly funny and one of the smartest writers I’ve ever worked with, although unpleasant and mentally unbalanced.”

Groening and Simon would never have had the chance to squabble if it weren’t for producer James Brooks. (You may know him from such quality programming as The Mary Tyler Moore Show and Taxi.) The Simpsons would usher in an unprecedented age of popularity for adult-oriented animation, but network executives at the time were wary of how much the experiment would cost. Brooks, revered for his success in both TV and the movies (Terms of Endearment, Broadcast News, Big) had the development of the show written into a renegotiated contract with Fox.

Brooks’ reputation allowed the show to operate with an unusually low amount of flak from the suits, and it helped that the biggest suit of all — Rupert Murdoch — was a fan of the show. Wanting to establish his young network’s bona fides, he even moved The Simpsons to run opposite The Cosby Show on Thursday nights. “Cosby must be coming to the end of his run,” Murdoch boldly — and accurately — predicted. “[H]e’s been there forever.” (Simon, peeved at his show being put in such a tough spot, created the vacuous and vaguely Cosbyesque character of Dr. Hibbert to vent a little.)

The business of getting the show on its feet is handled well, but the book unsurprisingly takes off when we meet the writers. Anne Spielberg, Steven’s sister, has said, “Jim [Brooks] believed — and was the only person in town at that time, and maybe still now — that the writers were the center of the project, that it was a writer’s medium.” The early writing teams on The Simpsons are the stuff of legend, and even were at the time — we learn here of one writer who was fired after three months; he was so intimidated by the room that he hadn’t pitched a single joke for fear of embarrassment. And maybe no legend is bigger than that of George Meyer, “somewhat of a shibboleth in the comedy-writing community.” Ortved relies heavily on excerpts from two of the only substantial pieces about the mysterious Meyer — a 2004 interview in The Believer and a 2000 profile in The New Yorker — that are well worth reading in their entireties.

Other former writers did speak with Ortved, including Tim Long, who recalls listening to another writer tell a story and thinking, “I could die here. I’m six minutes into this laugh and it’s not ending. That’s not an atypical experience. And I’m not an easy laugh.” That reminded me of this anecdote from David Owen’s piece in The New Yorker:

I recalled a story that Mike Scully had told me earlier, about the most intense laughter he had ever heard in the rewrite room. The incident had occurred several years before, on a day when the staff was working on a subplot in which Homer, at a police auction, buys an impounded muscle car that formerly belonged to the town’s resident criminal, Snake. Snake wants the car back, so he escapes from jail and contrives a recovery scheme worthy of Wile E. Coyote: he stretches a wire across a road in the hope of decapitating Homer as he drives by. The wire misses Homer, but his car is followed closely by another.

“The driver of the second car is holding a sandwich at a ridiculous angle high up over his head and saying, ‘I told that idiot to slice my sandwich,’ ” Scully explained. “That’s where we were going with the joke. But then George suddenly said, ‘What if the wire cuts off his arm?’ That made the people in the room laugh so hard that they were coughing, they were literally choking because the joke was so unexpected. It was a shocked kind of laugh, and it just started rolling, one of those laughs that build the more they reverberate through you.”

Ortved is a perceptive enough devotee that he understood the need for Conan O’Brien to have his own chapter; not just because O’Brien is the show’s most famous alumnus, but because he most perfectly represents a certain pivotal strand of its DNA. (It doesn’t hurt that O’Brien is a good quote. On reclusive writer John Swartzwelder: “[H]e’s this incredibly good-looking guy; he looks like a turn-of-the-century constable; he looks like someone who would arrest an anarchist for throwing a bomb at Archduke Ferdinand’s carriage.”) When O’Brien was named David Letterman’s successor in 1993, Simpsons fanatics were the only people not scratching their heads. They already knew him as the credited writer of legendary scripts, most notably “Marge vs. the Monorail,” a parody of The Music Man in which Springfield tries to reverse its fortunes by building a high-speed rail service.

Former staff writer Brent Forrester said, “Conan’s monorail episode was surreal, and the jokes were so good that it became irresistible for all the other writers to write that kind of comedy. And that’s when the tone of the show really took a rapid shift in the direction of the surreal.” Episodes credited to O’Brien managed this surrealism brilliantly, but they also planted the seeds for crasser, zanier shows like Family Guy and South Park to emerge — and for The Simpsons to become weakened, in turn, by the influence of its spawn.

Ortved is not a passive oral historian, not just a human cassette recorder. In fact, his opinions are the loudest and clearest in the book: he calls Mike Scully, who took over as showrunner after Season 9, “the man at the helm when the ship turned toward the iceberg,” and he calls Al Jean’s ensuing decade as showrunner a “Mugabe-like stewardship.” While he’s right that the show isn’t what it used to be, and it’s nice to have a viewpoint shaping the material, Ortved’s increasingly forceful appearances in the text highlight just how subjective this history is. They also serve as reminders of who isn’t here.

Ortved rightly says that “the contribution of the actors in making these characters believable cannot be overstated.” But because of the book’s unauthorized nature, none of the cast members — save for Hank Azaria — talked to him (we get precious few snippets of them from other sources). While the renegade tone allows Ortved to drop in a note about Nancy Cartwright, the voice of Bart, being a “devout member” of Scientology, it would have been more enjoyable to have extended reminiscences from Julie Kavner (Marge), Dan Castellaneta (Homer), and the rest of the show’s brilliant voices.

The omissions aren’t really Ortved’s fault, though, and most of those missing in action aren’t truly missed; it’s hard to imagine the real higher-ups like Groening and Brooks saying anything unguarded or provocative at this stage in their money-making juggernaut. It may be a ragtag group assembled here, but the book is a testament to a lasting love, which might be best summarized by O’Brien:

I’m constantly, no matter where I go in the world, running into people who know which episodes of The Simpsons I worked on, and they’re quoting lines to me. I think long after my Late Night show is gone, the Simpsons episodes I worked on will always be in the ether. People will be watching them on some space station, like, two hundred years from now. That’s a nice feeling.

John Williams is the editor of The Second Pass.

Mentioned in this review: