(Editor’s Note: The following essay is taken from City Secrets Books: The Essential Insider’s Guide

edited by Robert Kahn and Mark Strand, a beautifully designed compendium of personal essays recommending little-known or under-appreciated books, published by Fang Duff Kahn. The collection’s 158 contributors include Jane Smiley, Calvin Trillin, C.K. Williams, Deborah Eisenberg and Scott Simon. A portion of the book’s proceeds will be donated to First Book, a national organization that gives children from low-income families the opportunity to read their first new books. This is the third of four essays from the book that will appear on The Second Pass.)

Reviewed:

Belinda by Maria Edgeworth

Oxford University Press, 544 pp., $15.95

Maria Edgeworth might be the most important nineteenth-century novelist to have gotten lost in the twentieth. Like Fanny Burney before her and Mary Shelley after her, Maria was raised in the home of a famous father. Richard Lovell Edgeworth was an amateur scientist, a man of letters, and an “improving” landlord who returned from England to Ireland in 1782 with his thirteen-year-old prodigy of a daughter. Under his tutelage, at a tender age she was already conversant with the works of Adam Smith, but her literary education was also remarkable. She read widely and went on to write in many genres, sometimes in partnership with her father. In particular, she developed the new form of “national tale” in a series of novels about Ireland that inspired Walter Scott to try something similar for Scotland. The result was the Waverley novels. She was an innovator in domestic fiction as well, and her influence on Jane Austen is palpable.

Her first success, Castle Rackrent, was in the genre of the Irish tale, one narrated by an illiterate servant whose master’s Big House is gradually taken over by the machinations of the servant’s son. The use of the servant narrator pioneers a strategy later used in Wuthering Heights and The Remains of the Day.

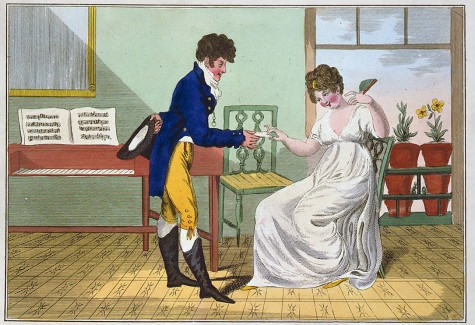

Belinda, set in England, is Edgeworth’s first triumph in the realm of domestic fiction. And though it helped shape the work of Austen a decade later, it reads like an experimental variation on Austen conducted before the fact. It is easiest to give the flavor of this remarkable book by pointing to three singular features about its plot and characters:

1. The titular heroine, an exemplary woman orphaned at a young age, is sent by her aunt in Bath to the house of an aristocrat in London with the hope (on the aunt’s part) that she will find a fit husband. The aristocrat, Lady Delacour, flamboyant rouée estranged from her alcoholic husband, nurses a secret malady in her breast (literally), which, we later learn, resulted from the kickback of a rifle during a duel she had with another woman, both of them dressed in men’s attire. The origin, meaning, and cure of this injury is crucial to the story.

2. Many of Jane Austen’s novels turn on a contest between the marriageable young heroine’s first and second affections, usually in the form of an irresponsible infatuation followed by a more sober and steady connection. In Austen, the result is predictable: not the flashy Churchill for Emma Woodhouse but rather her courtly senior, Mr. Knightley; not the dashing Willoughby for Marianne Dashwood, but rather the avuncular Colonel Brandon. In Belinda, too, the marriage plot turns on a pairing of roughly this sort. In London, early on, Belinda meets the multitalented wit and man of society Clarence Hervey, friend of the problematic Lady Delacour. It is a connection that Lady Delacour seems to encourage. Later, at the home of Lady Anne Percival, the saner and more wholesome mentor to Belinda, the young heroine meets Mr. Vincent, a West Indian planter and a man far less flamboyant than Hervey, and this apparently wiser match is encouraged by Lady Anne. But remarkably, as though reversing a formula that Austen herself had not yet perfected, Edgeworth has her heroine make the match with the flamboyant lover. And it is one that proves both good and sound.

3. In a scene that takes place at the Percivals’ home, some children, including a young daughter of Lady Delacour who no longer lives with her mother, are gathered around a fishbowl, tapping lightly on its sides. They are interrupted by the jovial Dr. X, a physician who will eventually diagnose and heal Lady Delacour’s breast injury, who asks what they’re up to. They explain that they are trying to determine whether the goldfish can hear the tapping of their fingers or are responding only to the vibration it creates in the water. The doctor explains to them that they are debating a vexed question in contemporary natural philosophy, one explicated in some detail by the learned Abbé Nollet. Later in the chapter, when Lady Delacour comes to visit, someone makes a remark that causes her young daughter to blush. We are left to wonder how to connect the physiology of human blushing with the puzzle of the goldfish bowl.

Belinda is a book that offers lively engagements with late-Enlightenment writings in literature, philosophy, and science. But it can engage the contemporary reader as well. Like much of Edgeworth’s other innovative narrative writing, it presents fiction itself as a kind of moral laboratory. As with many laboratories, it is a fun place to be, and you can learn a lot there.

James Chandler is a professor of Cinema and Media Studies and the Franke Professor of English at the University of Chicago, where he directs the Franke Institute for the Humanities. His books include Wordsworth’s Second Nature, England in 1819 and The Cambridge History of English Romantic Literature.

Mentioned in this review:

Belinda

Castle Rackrent

Waverley

Wuthering Heights

The Remains of the Day

Emma

Sense and Sensibility