Reviewed:

Reviewed:

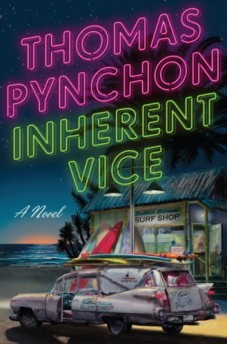

Inherent Vice by Thomas Pynchon

The Penguin Press, 384 pp., $27.95

A screaming comes across the sky. It’s the sound of another noir novel by a writer of American literary fiction rocketing into bookstores across the land. Several months ago, Denis Johnson’s Nobody Move, the sort of book reviewers inevitably call “lean,” was published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux after being serialized in Playboy. And now, shrieking closely behind through the stratosphere is Thomas Pynchon’s private eye thriller Inherent Vice. Should readers duck and cover?

It would be understandable if they did. Johnson and Pynchon are brilliant writers, but too often, a novelist who has made his reputation on more original entertainments resorts to crime novels (or other standard genres) when his imagination decides to take a busman’s holiday. Norman Mailer’s Tough Guys Don’t Dance is an inglorious example, and I say this despite Mailer’s expressed fondness for his bastard child. So is Martin Amis’ Night Train, a fast ride to nowhere.

It’s not that these books are terrible, just that the noir flirtations of such writers maroon their stories in a no-man’s land between the unpretentious plot machines of genuine genre novelists and the piercing, original takes on reality that are the measure of the best novelists. The language may huff and puff in true literary style. But when writers merely play at noir, their tough-talking protagonists usually come across as smirking parodies, standing in the shadows of the archetypal detectives and private eyes, the badasses born of the sincere efforts of novelists who have no choice but to labor in the salt mines of their genre. The sheriff of Jim Thompson’s The Killer Inside Me would make Mailer’s tough guys dance whether they wanted to or not. A novelist pays for the sin of thinking himself superior to his form by writing a bad book.

So I feared the worst at the news that Pynchon had written a caper about the adventures of a private dick. Couple this anxiety with a possibly dubious nostalgia for the way the publication of a Pynchon novel was once upon a time a culturally mesmerizing event, long rumored and eagerly awaited. The gap between 1973’s Gravity’s Rainbow and 1990’s Vineland, for instance, seemed endless and was marked with false alarms of books that never saw the light of day — a 900-page fiction about the Civil War, for instance.

In olden times, it was possible to see a new Pynchon novel as talismanic, a coded summons from the far side, or better, a gnostic message from our own side. (There was definitely an Us versus Them mentality afoot in those days. Villainy is muddled now.) Readers immersed themselves in books like V., The Crying of Lot 49 and Gravity’s Rainbow the way one of Pynchon’s characters entered a jazz club in the Fifties — with the expectation of joining a hip community that communicated with secret signs, the knowledge of which put an initiate, bemused and superior, at right angles to the rest of American society.

That Pynchon refused to appear (an old-fashioned form of dematerialization also practiced by God), that he did not deign to be photographed or interviewed or promoted like a MacBook, that he allowed Professor Irwin Corey to stand in for him at the National Book Award ceremony of 1973, only added weight to the appearance of his real stand-in — the novels.

So here, quite unexpectedly, only a year or so after the publication of Against the Day, a fiction colossal at the very least in size, is another Pynchon novel. The good news is that Inherent Vice is an honorable effort indeed, and shall we say, quite Pynchonian.

It is the story of Larry “Doc” Sportello, a private eye who is visited in the spring of 1970 by Shasta, a former girlfriend for whom he still pines. Her current boyfriend, the real estate developer Mickey Wolfmann, has disappeared. He may have been kidnapped. Of course, he’s married to someone else. And Shasta wants Doc to find him. Anyway, that’s what she says. And so begins this thriller, as have so many others, with the appearance of a good-looking woman (in this case, she’s wearing a bikini bottom and a Country Joe and the Fish T-shirt) who has a problem that may not be as it seems.

This is the dawning of the Age of Nefarious. Charles Manson has recently been arrested for the Tate-LaBianca murders, signaling the souring of a sweet countercultural vision for a new America that, if only for a tantalizing moment, seemed realizable, at least to those who had ingested enough hallucinogens. Doc mourns “how the Psychedelic Sixties, this little parenthesis of light, might close after all, and all be lost, taken back into darkness…” On an only somewhat less troubling note, he also worries that his Los Angeles Lakers are blowing the NBA finals to the New York Knicks.

LSD appears to have given Doc a sixth sense about people and the unfolding of events that proves useful in his line of work. “A private eye didn’t drop acid for years in this town without picking up some kind of extrasensory chops, and truth was, since crossing the doorsill of this place, Doc couldn’t help noticing what you’d call an atmosphere.”

Conspiracy is the organizing principle of Inherent Vice. That this is a noir novel merely makes explicit an underlying structure common to all of Pynchon’s fiction in which paranoia, delusion and momentary enlightenment alternate at a dizzying speed. Doc attempts to solve a mystery that may or may not be solvable, so dense are the thickets of information through which he must hack, so opaque the motives of nearly everyone he comes across, including old and new flames.

Against Doc’s humane ethos — if I’m not mistaken, he nearly always declines to be paid for his investigations, and he only shoots a couple of really bad guys — the forces of darkness wage their diabolical war. In no particular order, he battles the LAPD, the FBI, loan sharks utilizing an early version of the Internet, neo-Nazis (who also happen to be Ethel Merman fanatics), local vigilantes, a rock ‘n roll musician on the government payroll, shady developers, proto-New Agers and a mysterious organization known as the Golden Fang, which may in fact be run by dentists.

As Doc tries to figure out what happened to Wolfmann, the terms of the conspiracy keep mutating — one crook leads to another who leads to another who leads to another in an infinite regress of evil that eventually incriminates nearly everyone in the novel. Everyone, perhaps, but the pot-smoking, stewardess-boffing, late-night TV-watching and ultimately heroic Doc, who is given every chance to become a turncoat but who stays on, well, if not the straight-and-narrow at least the bent-and-wide-open.

Noir has never been quite so sunny as it is in Inherent Vice. It’s not just that the book is set mainly around Los Angeles and in Las Vegas. That’s true of Raymond Chandler’s fiction and many great films of the genre — Sunset Boulevard, for one. Despite the palm trees and swimming pools, those stories remain as dark as a car trunk with a corpse inside.

The sunniness radiates out of Doc. On the one hand, he is just a goofy private eye. On the other, he can be viewed in all of his cartoonishness as an embodiment of a gentle American communalism that incarnated itself so briefly in the Sixties (as it has in other epochs) that it appears to many as a mirage, an illusion to be spoofed and mocked and forgotten. Pynchon keeps glancing back at that moment with abiding tenderness, a true believer despite himself.

That he somehow manages to embody all of this in a noir thriller in which everyone is connected by tentacles of paranoia and conspiracy explains why Inherent Vice, an act of minor Pynchon, is still major enough. In a novel pervaded by darkness, its spirits are as high as many of its characters.

Will Blythe writes regularly for the New York Times Book Review. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, Rolling Stone, Sports Illustrated, and many other publications. He is the author of To Hate Like This Is to Be Happy Forever, a fan’s account of the North Carolina-Duke basketball rivalry.

Mentioned in this review:

Inherent Vice

Nobody Move

Tough Guys Don’t Dance

Night Train

The Killer Inside Me

Gravity’s Rainbow

Vineland

V.

The Crying of Lot 49

Against the Day

Sunset Boulevard