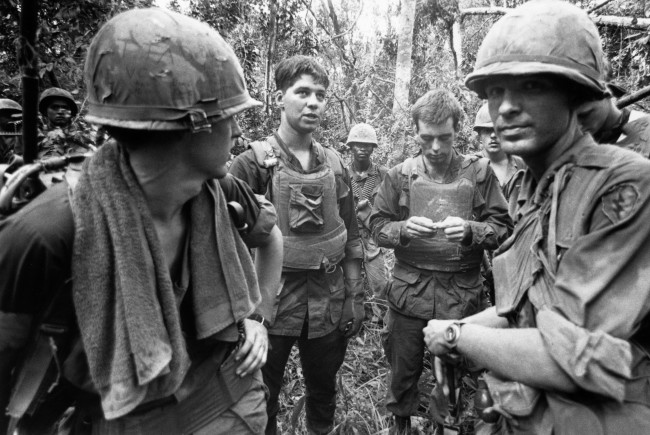

U.S. Marines in the jungle during the Vietnam War, November 4, 1968. (Photo by Terry Fincher/Express/Getty Images)

- Reviewed:

- Dispatches by Michael Herr

- Everyman’s Library, 296 pp., $24.00

Vietnam was the last calamity of the American Century.

It lamed or killed or corrupted everything it touched, and it touched everything. For 20 years we deformed ourselves around it – around our boardroom theories of containment and pre-emption, around a nightly network body count, around military vanity and corporate absurdity, around centuries of history we couldn’t be bothered to parse or even translate – until whatever America once understood as valor or language or sanity, grace or patriotism, fed back to us only paranoia and dread. We beat our plowshares into spreadsheets, and all our money and throw-weight and circular logic bought us only ghosts. Ghosts enough to haunt every street in America and every corridor in Washington.

From 8,000 miles away, Vietnam surrounded us. Fifty years later, it surrounds us still.

Mired now in two faraway wars, each of which carries the echo of our heartbreak in Vietnam, the reappearance of one of the seminal books on Americans at war is a kind of dark gift from history.

Michael Herr’s Dispatches, beautifully republished in a new edition by Everyman’s Library with an introduction by Robert Stone, is the most visceral, lyrical and powerful of the books that came out of the Vietnam War. In its immediacy and honesty, tireless reporting and unflinching observation, it is somehow both the book most of its own time and the most timeless. On the long shelf of great works about America’s slow-motion collapse in Southeast Asia – In Pharaoh’s Army, The Things They Carried, A Rumor of War,The Quiet American, Fire in the Lake, Going After Cacciato, Dog Soldiers – it stands alone.

I first came to Dispatches in 1977, the year of its original publication. I was twenty, a callow American kid who missed the draft by 18 months and lived every day of his life in the lattice of shadows cast by the Cold War and Vietnam and the American military-industrial complex. We were two years out of Saigon and three years out from the wreckage of the Nixon Administration, and there was still no sense anywhere that sense could be made of anything. The ’60s had come and gone, cutting us loose from the old verities, but no point on the compass now seemed safe, or even sane. There had been no national reckoning, no accounting of how or why anything had become what it had become. We plunged forward even as the deeper truths of what it now meant to be an American remained hidden.

I found many of those truths in Dispatches. The book scalped me. And does to this day.

Herr’s singular achievement lies not only in capturing the epic cruelty and futility of that war, of all wars, but in finding the beauty and elaborate seductions in it, too. Because the book is episodic, he seems somehow everywhere at once in Vietnam – Hue, Khe Sanh, Saigon – everywhere in time, all at once, and yet somehow always in an emphatic present moment.

He bears a rare, near-perfect witness to whatever he hears and sees; to the honor or depravity or hopelessness of every grunt he meets; to the brutal poetry of killing; to the moral vacuum of the American command monolith and to the churn and lurch of the great machine it engineered to protect and destroy us.

Dispatches is a flawless rendering of ruined human spirit and the madness of authority. In its contribution to craft and artistry in 20th century letters, it is, I believe, the heir and equal to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

Like all great books, it teaches you how to read it in the first few lines:

Going out at night the medics gave you pills, Dexedrine breath like dead snakes kept too long in a jar. I never saw the need for them myself, a little contact or anything that even sounded like contact would give me more speed than I could bear. Whenever I heard something outside of our clenched little circle I’d practically flip, hoping to God that I wasn’t the only one who’d noticed it. A couple of rounds fired off in the dark a kilometer away and the Elephant would be there kneeling on my chest, sending me down into my boots for a breath. Once I thought I saw a light moving in the jungle and I caught myself just under a whisper saying, “I’m not ready for this, I’m not ready for this.” That’s when I decided to drop it and do something else with my nights.

From the beginning, you know how personal the reporting in this book is going to be, how intimate, and how excruciating. You know the risks Herr took and how much he suffered to take them. And that voice, that narrative voice, as hip as it is eloquent, as jittery as it is sure, as smart and cutting and descriptive as it is deadpan. I had never read anything like it before, and haven’t read anything to rival it since.

Herr set out to write a few pieces for Esquire, to be a “war correspondent,” without knowing what any of that might really mean or finally do to him. Instead, what he wrote became this transformative work of nonfiction.

So powerful was its effect that for the next decade it was the well from which popular culture drew its perceptions of the war. Even movie fans unfamiliar with the book will recognize Dispatches as the source material for sequences in at least two films of that time. In his work as a screenwriter for both Full Metal Jacket and Apocalypse Now, Herr borrowed his best from himself. Even secondhand, his voice was clear and strong. I note with sadness how long ago that was, and despite how much has come and gone, how much remains unchanged.

Trapped as we are now in a state of perpetual war – terror war, corporate war, imaginary war – Vietnam remains our original post-atomic sin, the American fall from grace that broke the hearts and minds of one generation in the very moment it birthed and crippled the next. The history of that fated place is everywhere in us and around us. And no book tells that terrible story better.

For its rude truth, for the insane music of its words, for its humor and its passion and its empathy, for its fierce humanity and dignity, for its willingness to describe so bravely the terrifying burden of America’s love and the workings of our hate, Dispatches is a work of genius, a remarkable, impeccable sketch of the endless hallucination that was Vietnam.

Jeff MacGregor is the author of Sunday Money: Speed! Lust! Madness! Death! A Hot Lap Around America with NASCAR. He is currently a Senior Writer at ESPN. He has written for Sports Illustrated, The New York Times, The New Yorker, Esquire, and many other publications, and he is an eight-time National Magazine Award nominee.