Reviewed:

Reviewed:

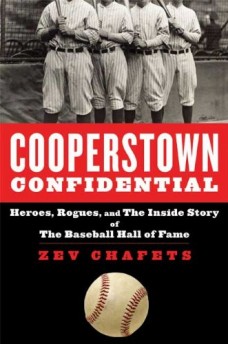

Cooperstown Confidential: Heroes, Rogues, and the Inside Story of the Baseball Hall of Fame by Zev Chafets

Bloomsbury, 256 pp., $25.00

There are two approaches to baseball’s Hall of Fame, the earnest and the playful, and they are rarely combined. If you view the museum in Cooperstown, New York, as an august shrine that bestows deserved immortality on its members, you will view its decisions with the scrutiny and piety of a Supreme Court justice. If you see it, like I do, as a tourist trap and nationwide parlor game, you will have lively conversations with fellow fans about who deserves entry, but the ultimate decision of a group of sports writers about who gets past the gate won’t occupy — and certainly won’t disturb — your thoughts for any considerable amount of time.

Zev Chafets’ Cooperstown Confidential, a slender book that serves as both a revisionist history of the Hall and a polemic in favor of socially liberal admission policies (Pete Rose and steroids users will rejoice if Chafets has any impact on voting patterns), manages to be earnest and playful, though not in the traditional ways described above. Earnest because it spends more time addressing issues like racism and commercialism than whether Bert Blyleven deserves a plaque; and playful because it gleefully spits in the face of anyone who thinks the Hall’s (very thin) Puritanical sheen is anything but a “public relations sham.”

Rogers Hornsby’s name may not echo in the popular imagination quite like that of Babe Ruth or Mickey Mantle or Willie Mays, but very few players had careers so clearly worthy of the Hall of Fame. Today, if a player were to hit .400 or better for the duration of one season, it would be the biggest sports story in years. Hornsby once hit a cumulative .402 over the course of five consecutive seasons.

Oh, he was also allegedly a member of the Ku Klux Klan. (Chafets dispenses with the “allegedly” part — briefly researching it, I could find only allegations — which is in keeping with his aggressive tone throughout.) The point being that Hornsby and other ne’er-do-wells like Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker sit with their corrupt feet up in Cooperstown while today’s moral majority guard against the enshrinement of anyone less pure than a Boy Scout.

The complication, of course, is that today’s Hall debates rage around the issue of performance-enhancing drugs, not off-field behavior. This doesn’t slow Chafets down for a moment. He presented his argument about steroids in condensed form in a recent op-ed piece for the New York Times, in which he wrote:

Since the dawn of baseball, players have used whatever substances they believed would help them perform better, heal faster or relax during a long and stressful season. . . . Purists say that steroids alter the game. But since the Hall opened its doors, baseball has never stopped changing. Batters now wear body padding and helmets. The pitcher’s mound has risen and fallen. Bats have more pop. Night games affect visibility. Players stay in shape in the off-season. Expansion has altered the game’s geography. And its demography has changed beyond recognition. Babe Ruth never faced a black pitcher. As Chris Rock put it, Ruth’s record consisted of “714 affirmative-action home runs.” This doesn’t diminish Ruth’s accomplishment, but it puts it into context.

In 1944, the Hall added Rule 5 (or, the “Character Clause”) to its election requirements. In Confidential, Chafets calls it “the only condition imposed by the Hall on its electors,” and shares its wording with his own italics added: “Voting shall be based upon the player’s record, playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character and contributions to the team(s) on which the player played.”

I’m not sure why he kept the italics going for “contributions to the team(s),” since this presumably means competitive contribution and not how many souls they saved in the locker room. And on those baseball contributions, Chafets doesn’t have a lot to say. Within pages, he writes that “Albert Belle was a Hall of Fame player by almost any standard” and “I don’t know if [Gary] Sheffield belongs in the Hall of Fame.” I think of Sheffield as a lock and Belle as a player whose lack of longevity will hurt him as much as his attitude. Chafets ignores the longevity issue, simply noting that Belle played the minimum number of years necessary for HoF consideration, and argues that focusing on Belle’s very real flare-ups — throwing a baseball (hard) at a fan, for one — is just coded language for racism. It’s a good example of how Chafets occasionally lets his theories get ahead of the facts. (Even if it’s a silly parlor game, Belle is just not an inarguable Hall of Famer).

About less controversial characters, Chafets still seems most interested in taking the starch out of the process: “It’s not that [the recently elected Goose] Gossage doesn’t belong in the Hall of Fame. It’s just that he doesn’t necessarily have to be there.” And one wonders, So what? The borderline cases are the point of the Hall of Fame, in more ways than one. The game’s indisputable pillars — Ruth, Mays, Mantle, Aaron, Robinson, et al. — don’t need Cooperstown to keep their memories alive. Their legends would survive even if we suddenly reverted to an exclusively oral culture and only learned things around campfires. It’s Gossage — and Jim Rice and Blyleven, Belle and Sheffield — who make the Hall fun for a fan base famously devoted to parsing arguments.

So on some pages, one wishes that Chafets would loosen his belt a bit. But he’s right to reframe the debate about steroids. Setting himself up as a foil to romantics like George Will, who believe that “baseball players once existed in a pure state,” Chafets doesn’t stop at pointing out that many players once relied on uppers, cocaine and spitballs to get them through a long season, or that equipment and even the playing field have changed through the years. He lists scientific advancements that are thoroughly accepted as performance enhancers, like LASIK surgery or Tommy John surgery for pitchers’ arms. He refers to members of world-class orchestras and top trial lawyers needing to take beta blockers to lessen stage fright, pilots and surgeons relying on “cognition enhancers,” and all those couples who pop up (pardon the pun) in ads during baseball games, lounging in His and Hers bathtubs on an outdoor deck, staring at a misty vista and waiting for the Cialis to kick in.

Chafets is sometimes a bit too cavalier for my taste in lumping steroids with the rest of society’s better living through chemistry. After all, a pilot is only “cheating” to get ahead in a non-zero-sum game; everyone on the plane wants to get home safely. In a baseball game, a non-enhancer could be at a disadvantage, and Chafets’ solution — to allow all players to use freely — is more complicated than he allows. I say “could” be at a disadvantage because Chafets also wisely points out that the positive effects of steroids on performance are far from proven. Mark McGwire and Barry Bonds broke the 70-home run barrier, but that was after Roger Maris had hit 61 a few decades before. Chafets reminds us that Babe Ruth hit 54 dingers in one season when the previous record (by a player other than Ruth) had been just 24. “Sometimes transcendent performances,” he writes, “are simply transcendent.”

John Williams is the editor of The Second Pass.

Books mentioned in this review: