Reviewed:

Reviewed:

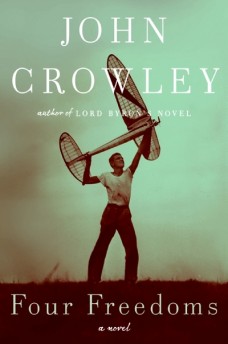

Four Freedoms by John Crowley

William Morrow, 400 pp., $25.99

Though John Crowley is one of my favorite writers — I consider his Aegypt tetralogy one of the most impressive achievements in contemporary fiction — I’ll admit that I approached his new novel, Four Freedoms, with trepidation, solely because of its setting: the American home front during World War II. Crowley’s love of his characters shines through all his writing. He is the opposite of a domineering fatalist like Thomas Hardy. Even when his characters do wrong or suffer, we always sense that Crowley is trying to give them the benefit of the doubt or to understand (and even help them understand) why the fates have chosen to buffet them so. It’s one of the reasons that his novel Little, Big (1981) has a substantial cult following: it’s impossible to read the deeply sympathetic accounts of his characters’ failings and not think that, yes, this is how we, too, would hope to be judged one day. World War II, however, is already so wrapped up in nostalgia, so held up for admiration, so packaged, that it would seem to hold substantial risks for such a generally gentle writer. One could imagine the resulting work as a treacly slop of honorable behavior and received opinion, all Andrews Sisters and FDR, ration cards and Rosie the Riveter.

I should have had more faith. Four Freedoms, though unquestionably admiring of those who took on the challenges of the Depression and the war, is far from an exercise in generational hagiography. It’s more like an elegy for an America that never quite was, a land of broad hopes that shimmered into view for the duration of the war, only to be undone by Cold War paranoia, social unrest and simple greed. In telling the story of a group of workers brought from all over the United States to staff a bomber plant in Oklahoma, Crowley paints a portrait of the country as a place of rapid change and new opportunity.

Though most accounts of life during World War II focus on sacrifice, in reality, and unlike almost everyone else in the world (including their own relatives and friends who were serving overseas), Americans found themselves in an unexpectedly good situation, rocketed out of the Great Depression by a new industrial economy in which jobs were plentiful, pay was good and the departure of so many men transformed longtime understandings of just who was suited for what sort of work. Concerns about loved ones in danger certainly tempered the mood, but as the radio shows and movies of the period suggest, a certain national effervescence was nonetheless inescapable. A huge number of Americans found themselves with steady jobs and money in their pockets for the first time in memory — money they gladly spent on movies, sports, music and all the trappings of a quickly growing consumer culture.

Crowley’s novel is the first I’ve encountered that successfully conveys that spirit. Against a meticulously detailed background of the period, he portrays a handful of characters for whom the war has opened up new possibilities. At the center of the action is Prosper Olander, who can barely walk because of botched surgery to correct a spinal deformity. After a lifetime of being essentially shut out of the working world by his disability, he wholeheartedly embraces the openings created by the dearth of able-bodied men. From the moment of his arrival, the bomber plant seems to him almost a utopia. For the first time, he’s respected and presumed to have something to contribute. As he embarks on a series of romantic relationships, we see that the women he loves — a softball pitching phenom, a put-upon young mother and a lonely “goodbye bride” — feel much the same: the absence of male control and the concomitant relaxing of gender roles have given them an unprecedented autonomy and self-confidence.

Because the plant has been built essentially in the middle of nowhere, the workers are all housed on its grounds in more or less similar conditions, living and working and relaxing together. This experience, of young people uprooted from their homes and jumbled together, is similar to how later generations would live at college. The close quarters and hothouse atmosphere — plus the sense of impermanence and uncertainty brought on by the war — inevitably lead to intense friendships and loves, rapid personal growth and change. The sense of shared purpose at the plant only heightens the pitch: to have important work to do, to be appreciated for that work, and, when the work is finished, to be truly free to decide how to live your life — what more could one need?

But we’ve yet to prove ourselves capable of creating perfect societies, and Crowley knows this factory town can’t help but fall short. For one thing, not quite everyone lives in similar housing. Without the issue ever being formally discussed by management, black workers are assigned their own dormitory. And while women at the plant have more freedom than they’ve known, the few husbands present still expect to rule over their wives. One woman rouses her husband to explosive anger simply by deciding herself to follow him to the plant. Meanwhile, as the war drags on it becomes harder for everyone to maintain a sense of group sacrifice. In the bitter winter of 1944-45, Crowley writes, “we were tired of all that, so tired, and so back came Mr. Black in a big way, the stuff you wanted was there if you could find it, gas traded for whatever you had, farm-butchered beef and pork removed from the system and sold out of meat lockers that you knew about if you knew.”

The intertwined promises and pitfalls of the historical moment seem to find their purest expression, for Crowley, in sex. As in so much of his work, sex is central to Four Freedoms, bringing people together, even healing them. It is in sex that Prosper, congenitally kind and open, shows his best self; he is gentle and unpossessive, forever pleasantly surprised that any woman would give him such a gift. But even sexual love so freely given has its dangers, both physical and emotional, most of them borne by the women. Despite good intentions, jealousy proves almost inescapable, and an unplanned pregnancy presents a frightening reminder of the social constraints that remain.

Four Freedoms tells these stories in episodic fashion, as a series of overlapping portraits, relying very little on a propulsive plot. As each new character of any importance is introduced, the narrative pauses for a moment (or longer) to give an account of his or her back story. The technique doesn’t always work — the opening section about the factory’s owners, for instance, seems peripheral to what comes later — and an impatient reader could be forgiven for wondering at times whether the small developments in each of Prosper’s relationships are ultimately going to add up to anything larger. But Crowley’s characters — especially the women — are so richly imagined that their multiple viewpoints enrich our understanding of Prosper, his times and our nation’s history. By the end of the war, Prosper sees the end of the relatively cozy life he’s been able to make for himself, and we ache for what he’s lost, even as we hope along with him that he will retain at least some of his new liberty.

The novels about World War II that I admire most — James Gould Cozzens’ Guard of Honor (1948) and James Jones’s From Here to Eternity (1952) — take place far from the drama and danger of the battlefield, focusing instead on what the disruptions of war, even at a distance, do to our sense of our selves and our place in society. While Four Freedoms may not quite reach the level of those classics, it’s an honorable addition to their company.

In addition to holding a full-time job at the University of Chicago Press, Levi Stahl is the poetry editor for the Quarterly Conversation, the Chicago editor for Joyland and a blogger at I’ve Been Reading Lately. He has written for the Poetry Foundation, the Chicago Reader and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, among others.

Books mentioned in this review:

Four Freedoms

Little, Big

The Aegypt Tetralogy: The Solitudes, Love & Sleep

, Daemonomania

, and Endless Things

Guard of Honor

From Here to Eternity