Reviewed:

Reviewed:

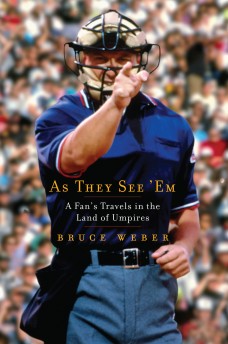

As They See ‘Em: A Fan’s Travels in the Land of Umpires by Bruce Weber

Scribner, 352 pp., $26.00

To say that Bruce Weber’s As They See ‘Em is the only book you need to read about baseball umpires is both a compliment to Weber and yet another insult to umps, who have written (well, co-written) a surprising amount of autobiography. Eric Gregg, Durwood Merrill, and Ken Kaiser published accounts of their time in the game. Ron Luciano fathered five books, and may have had less trouble generating material for a sixth than another punning title: his bibliography includes The Umpire Strikes Back, The Fall of the Roman Umpire, and — this one’s actually pretty good — The Remembrance of Swings Past. Add a few historical surveys of the job and a couple of titles from the microscopic niche of Books By Umps Representing Progressive Politics — Dave Pallone’s Behind the Mask, about his struggles as a gay man in the job, and Pam Postema’s You’ve Got to Have Balls to Make It In This League — and you have a more than reasonably sized literature by the men (and sole woman) in blue.

“Umpiring has no forgiveness built into it,” Weber writes, correctly noting that baseball “has a fetish about failure. That the best hitters succeed a mere third of the time is familiar enough to be a cliché. . . . Only the umpire is expected to consistently subdue the challenges of the game.”

Those unforgiving fans might argue that they expect more from the umps because the umps have a much easier job than the players, but Weber does his best to prove that’s not true. In George Plimpton fashion, he begins on the road to the job himself, enrolling in one of the two schools from which Major League Baseball accepts new recruits. What he finds is that trying to determine whether a ball thrown at 98 miles per hour has passed through the theoretical patch of air known as the strike zone can be as difficult as trying to swat said ball.

The odds of becoming a big-league ump are long. There are only about 70 positions available, and “the men who are in them tend to hold on to them with the tenacity and durability of Supreme Court justices.” (When arguing with an ump, minor league managers have been known to gleefully scream, “You’ll die here!”) And those few who survive the minors — a job that barely pays a living wage (for five months a year) and involves regularly driving hundreds of miles at a time with a fellow umpire — don’t get much more respect when they reach the show. Fay Vincent, baseball’s commissioner from 1989 to 1992, and much friendlier to umpires than other higher-ups, said:

“The owners basically see them like bases. They say, ‘We need a base, we need an umpire, same thing. We’ve got to pay them, they’re human beings, but they’re basically bases.’”

Irascible manager Billy Martin once sent a Christmas card to umpire Jim Evans. The outside of the card read, “I hope you and your family have a wonderful holiday season.” Inside: “because you sure had a horseshit summer.”

(Martin’s card is one of many funny moments in the book. My favorite: a minor-league executive discloses what the world-famous Chicken charges for an appearance — $7,000 — and then earnestly tells Weber, “Please don’t print that; the Chicken’ll kill me.”)

So why would anyone in their right mind put themselves on a career track that will take the best years of their lives, pay them almost nothing for it, drown them in an avalanche of profanities, and likely leave them right back where they started? Weber would like to think it’s because of a higher calling, a fixation on justice and fairness as untarnished symbols: “Umpires exist . . . only to ensure that the greatest American game is played fairly, and for this selfless endeavor they are universally reviled.” But the umps he meets along the way — the book really takes off when he follows their lives and stories, after a somewhat repetitive start that establishes the “universally reviled” part — tend to shrug off suggestions of nobility.

Umps are taken for granted, without doubt. Their duty is perhaps the ultimate example of only allowing for notice when it’s done wrong. There is absolutely no credit or appreciation given, and buckets of blame, much of it unwarranted — proudly unwarranted. (General Douglas MacArthur, recently returned from Japan, visited the Polo Grounds in 1951, and said that he and his wife would “razz the umpire, even if we know he is right.”) And like anyone who believes that his authority isn’t met with adequate fealty, or that he’s on the periphery when he should be center-stage, umps often redress the situation by acting out and making an exaggerated show of their pettiest powers. In short, umps can be jackasses.

When Weber compares them to kings and army generals, or oddly writes that “[umpires] exist only in baseball” (referees in other sports may not be called umpires, but it’s silly to casually erase them from the picture when they arguably play an even greater and more controversial role in their sports), Weber gets overheated. He’s at his best when he takes a deep breath and rationally views the job for what it is:

. . . as the umpire you are neither inside the game, as the players are, nor outside it among the fans . . . the game passes through you, like rainwater through a filter . . . your job is to influence it for the better, to strain out the impurities, to make it cleaner, fairer, and more transparent without impeding it, corrupting it, changing its course, or making it taste funny.

Weber’s best defense of the umps is an implicit one. The games he chooses for closer inspection of their work might easily be guessed by baseball fans before reading the book. This is not a criticism. Over the course of the last 25 years, there have been a handful of high-pressure, indelible moments in which umps became the story, including a 1997 playoff game between the Braves and Marlins in which the strike zone enforced by Eric Gregg was roughly the width of a football field; Game 1 of the 1996 American League Championship Series, when 12-year-old Jeffrey Maier reached out and turned a Derek Jeter fly ball into a home run but wasn’t called for fan interference; and Game 6 of the 1985 World Series, in which Don Denkinger called a runner safe at first base when he was clearly out. Weber covers all of these.

Those games stand out because, of the tens of thousands of games played over that period, they were the ones when the ump was most clearly too large a factor at a critical moment.

It’s true that umpires blow calls. Of course they do. It’s also true that every time a call goes against the home team, no matter how obvious the evidence in the ump’s favor, there will be something between a smattering of boos and a tsunami of them. In this way, the umps get booed as often for being objective as for being subjective; they can be hated simply for representing a bad experience. Sure, our guy was a step slow, but you’re the one who called him out. This nicely illustrates the price one can pay in any walk of life just for observing and describing a reality that’s not to someone’s liking.

John Williams is the editor of The Second Pass.

Books mentioned in this review: