Reviewed:

Reviewed:

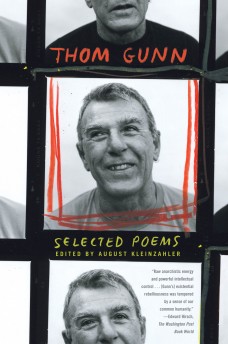

Selected Poems by Thom Gunn

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 128 pp., $14.00

Thom Gunn was one of those British ex-pats who moved to the States with extraordinarily mixed results. He did so at a time when poetry’s scope was being restricted. It was suffering a loss of its mid-century academic and formal spaciousness and becoming a discipline of pinched forms (if not ambitions), an art of diminished reach. He rode this constricting arc with some irony, because even as Gunn practiced a freer style in his later years, there was no stronger lover of formality, and no greater practitioner of formalism. As Auden said at Mt. Auburn Cemetery, honoring in some ways Gunn’s temperamental opposite, Henry James, he was a “master of nuance and scruple.”

Gunn arrived on the scene with Fighting Terms (1954) and A Sense of Movement (1957), the first published while he was still a student at Cambridge. These verses were formal in their loftiness, their removal from the world, their utilization of forms half a millennium old. When writing the latter collection, Gunn had already moved to California and was studying under Yvor Winters at Stanford. Winters worshipped the Elizabethans, particularly their work in lyrics. As Gunn described, “I had long liked the Elizabethans; I knew Nashe’s few poems well, Raleigh’s, and even some of Greville’s; Donne had been, after Shakespeare, my chief teacher. So I already shared some of Winters’ tastes, and though I liked the ornate and the metaphysical I needed no persuading to also like the plain style.” What all the Gunn-Winters mentors possessed was intelligence, the notion that poetry was not just musical speech but required intellectual penetration, a moralist’s critique of human behavior. The captive falcon in “Tamer & Hawk” (from Fighting Terms) thus reminds the falconer of his own, perhaps unrealized servitude:

As formerly, I wheel

I hover and twist,

But only want the feel,

In my possessive thought,

Of catcher and of caught

Upon your wrist.

You but half civilize

Taming me in this way.

Through having only eyes

For you I fear to lose,

I lose to keep, and choose

Tamer as prey.

The thinness of semantic demarcation between “choose” and “lose” here nicely conveys the master-slave relationship theme he mined from both Elizabethans and Jacobins (Jonson, et al.). Whether with humans or animals, brutality has its own dreadful music — the bells of shackles and the clink of chains.

By 1961, in My Sad Captains, Gunn was reaching beyond the style that caused critics to lump him with Larkin and Hughes. The move to California loosened something up in him. He addressed the change in a letter to the publisher Faber & Faber about a decade later:

The first half [of the book] is the culmination of my old style — metrical, rational, but maybe starting to get a little more humane. The second half consists of a taking up of that humaner impulse in a series of syllabic poems . . . which were really only a way of teaching myself to write free verse . . .

In the title poem, we see a delicate new freedom emerging:

One by one they appear in

The darkness: a few friends, and

a few with historical

names. How late they start to shine!

but before they fade they stand

perfectly embodied, all

the past lapping them like a

cloak of chaos.

Historical figures he once thought unassailable fall away, as surely and severely as the poetic forms of their ages. They still (both of them) stand “perfectly embodied” and “shining,” but are no longer the sole, authoritative paradigm. They are just another category in human and poetic taxonomies.

Then came the real break, in 1971, after the Sixties in the Bay Area had washed through Gunn like a cold jolt of morphine. “People make marvelous shifts,” Alice Munro wrote in her story “Differently,” “but not the changes they imagine.” Gunn had come out more openly as a gay man, taken a leave of absence from the Berkeley faculty, had some near-death experiences with hepatitis and some new-life experiences ingesting hallucinogens. What followed was Moly, a collection that defies classification and represents his apogee as an influential and quite visible poet, in addition to a merely accomplished one. The book starts with “Rights of Passage,” an unsurpassed Oedipal poem, with the possible exception of Auden’s elegy to Freud, which doesn’t take any first-person risks. In his introduction to the new Selected Poems, August Kleinzahler rightly judges “Rights of Passage” as one of “the thrilling moments in twentieth century poetry”:

Something is taking place.

Horns bud bright in my hair.

My feet are turning hoof.

And father, see my face

–Skin that was damp and fair

Is barklike and, feel, rough.

See Greytop how I shine.

I rear, break loose, I neigh

Snuffing the air, and harden

Toward a completion, mine.

And next I make my way

Adventuring through your garden.

My play is earnest now.

I canter to and fro.

My blood, it is like light.

Behind an almond bough,

Horns gaudy with its snow,

I wait live, out of sight.

All planned before my birth

For you, Old Man, no other,

Whom your groin’s trembling warns.

I stamp upon the earth

A message to my mother.

And then I lower my horns.

The poem is a dazzling merger of free will and fatedness. The deer-boy is liberated by acting out a genetically predetermined disposition. He is aware of it all, haughty but apologetic, mother-pleasing but cognizant that he must eventually buck her wishes as well. Transformation continues in the second, title poem, named for the herb the pig-men knew would throw off Circe’s spell and restore Odysseus’s crew to human form. Gunn here gives the nod to his newfound psychedelics, but seems also to be honoring any number of transfiguring processes, for “man cannot bear too much reality”:

I root and root, you think that it is greed,

It is, but I seek the plant I need.

Direct me gods, whose changes are all holy,

To where it flickers deep in grass, the moly:

Cool flesh of magic in each leaf and shoot,

From milky flower to the black forked root.

From this flat dungeon I could rise to skin

And human title, putting pig within.

I push my big grey wet snout through the green,

Dreaming the flower I have never seen.

As Edwin Muir noted, Gunn was “endowed with and plagued by an unusual honesty; his poems are a desperate inquiry, how to live and act in a world perpetually moving.”

The critics, especially in Britain, declared his career over with Moly. But all that San Fran freedom strengthened the timber of his voice, gave it an urbane, wizened maturity. Granted, there is some slackness, traceable to a slack time. One can take or leave “Listening To Jefferson Airplane: Golden Gate Park.” (“The music comes and goes in the wind / comes and goes on the brain.”) But the same atmosphere gave him “At The Centre,” an LSD description that is as structured a capturing of unstructured experience as Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” or Ginsberg’s “Wales Visitation.” From a rooftop, peaking on acid, Gunn wonders, “What is this steady pouring that / Oh wonder. / The blue line bleeds and on the gold one draws. / Currents of image widen, braid, and blend / . . . To one all-river.” The careful construction of surfaces, the imagistic scene-building are paused, buoyed up and lightened by the sudden “Oh wonder.” He registers a new architecture of reality, then stands in amazement at his own creation of it.

Gunn’s late career took on more somber subjects, including the plague days of the ’80s and ’90s AIDS pandemic. He avoided the disease, dying of heart failure at 74, but he followed the fate of many a comrade in cycles like The Man With Night Sweats. The abyss sucks at the realest thing we have, our physical constitution: “I have to change the bed / But catch myself instead / Stamped upright where I am / Hugging my body to me / As if to shield it from / The pains that will go through me / As if hands were enough / To hold an avalanche off.” The hands that wrote the poems also wrapped his lover in medicated sheets, emptied bedpans, held off the physical attacks of his charges who changed (yes, there are bad as well as good transformations), in an instant, from grateful patients to furies of dementia.

His experiences with death enabled Gunn to face things like his mother’s suicide, an event he had evaded for decades. In “The Gas Poker,” he wrenchingly wrote:

One image from the flow

Sticks in the stubborn mind:

A sort of backwards flute.

The poker that she held up

Breathed from the holes aligned

Into her mouth till, filled up

By its music, she was mute.

This new collection has that perfect, jacket pocket-fitting size, little more than a hundred pages. It traces the arc of a career with wisely spaced, representative snapshots. And the intro by Kleinzahler — who counts Gunn as a strong influence — is worth the price of the book alone.

Richard Wirick lives in Santa Monica, California, where he practices law and writes. He is the author of One Hundred Siberian Postcards, a memoir about the adoption of his daughter.

Books mentioned in this review: