Archives, January, 2011

Thursday, January 27th, 2011

Reynolds Price died last week at 77. Of his many, many works, I’ve only read The Surface of Earth

Reynolds Price died last week at 77. Of his many, many works, I’ve only read The Surface of Earth and The Source of Light

and The Source of Light , the first two books in a trilogy about the fictional Mayfield family. The New York Times obit said the trilogy “confounded critics.” I read them a long time ago — I remember them being highly stylized (and maybe maudlin), but also affecting.

, the first two books in a trilogy about the fictional Mayfield family. The New York Times obit said the trilogy “confounded critics.” I read them a long time ago — I remember them being highly stylized (and maybe maudlin), but also affecting.

At the news of his death, the Paris Review linked to the magazine’s 1991 interview with Price, conducted by Frederick Busch. It has several almost aphoristic winners, like: “The root problem is that cities are the least permanent things in our civilization. Any pebble on the outskirts of town stands a far better chance of lasting than New York City does.” And: “The chief harm in charging people for writing degrees is of course the lie you’re all but bound to tell — that each one’s a possible Conrad or Brontë — when most of them can’t even tell a good joke, much less the stories of this huge country.”

I was especially moved by this longer description of his relationship with his parents:

They were almost too lovable, which is something I’ve heard very few people say about their parents. I think both my brother and I, who were their only children to survive infancy, have all our lives been handicapped by the fact that we seldom meet human beings as loyal, affectionate, or continuously amusing as our parents were. They were both grand talkers, and my father also had a thoroughly first-class verbal and gestural wit. He was a great comedian — and I’m thinking of Charlie Chaplin when I say that — though he never had a moment’s training nor a moment’s professional opportunity to exhibit it. Among all his friends, he was absolutely everybody’s favorite person to see. By the time I was born in 1933, he was a very serious alcoholic — I don’t guess there are any unserious alcoholics — but he made a deal with God when I was born. My mother and I were both in danger during her labor — I was one of the last American bourgeois children born at home — and my father vowed to God that if mother and I survived he would stop drinking. We survived, and he did. It took him a couple of years, but he did.

Monday, January 24th, 2011

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

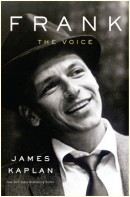

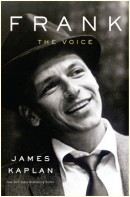

Geoffrey O’Brien reviews James Kaplan’s biography of Frank Sinatra, which covers the first third of the Chairman’s life: “The book’s tone often approaches the melodramatic, but it is melodrama honestly come by. This was a life lived, at least in these less guarded early years, as if to leave just such a gaudy record behind.” . . . Karl Kirchwey says that Gjertrud Schnackenberg’s new book of poems, about her husband’s illness and death, is “perhaps the most powerful elegy written in English by any poet in recent memory.” . . . Nicholas Carr reviews Douglas Coupland’s “pithy” new biography of Marshall McLuhan, which takes its title from one of the all-time great movie scenes. “Neither his fans nor his foes saw him clearly. The central fact of McLuhan’s life, as Coupland makes clear, was his conversion, at the age of twenty-five, to Catholicism, and his subsequent devotion to the religion’s rituals and tenets.” . . . Sam Sacks reviews two novels about the Holocaust, one from 1968 and recently translated into English, the other “eerie, brilliant” and “a remarkable achievement.” . . . Jessica Treadway says Siobhan Fallon’s new collection of short stories provides “often poignant, sometimes crude, and consistently compelling insights derived from the time she spent in Fort Hood, Texas, during her husband’s two tours of duty in Iraq.” . . . Stefan Collini reviews a new collection of 94-year-old historian Eric Hobsbawm’s writings on Marxism. . . . David Ulin says that a year after J.D. Salinger’s death, much about his life (and his work) remains a mystery, and that a new biography is, perhaps inevitably, “more an extended letter from a fan.”

Geoffrey O’Brien reviews James Kaplan’s biography of Frank Sinatra, which covers the first third of the Chairman’s life: “The book’s tone often approaches the melodramatic, but it is melodrama honestly come by. This was a life lived, at least in these less guarded early years, as if to leave just such a gaudy record behind.” . . . Karl Kirchwey says that Gjertrud Schnackenberg’s new book of poems, about her husband’s illness and death, is “perhaps the most powerful elegy written in English by any poet in recent memory.” . . . Nicholas Carr reviews Douglas Coupland’s “pithy” new biography of Marshall McLuhan, which takes its title from one of the all-time great movie scenes. “Neither his fans nor his foes saw him clearly. The central fact of McLuhan’s life, as Coupland makes clear, was his conversion, at the age of twenty-five, to Catholicism, and his subsequent devotion to the religion’s rituals and tenets.” . . . Sam Sacks reviews two novels about the Holocaust, one from 1968 and recently translated into English, the other “eerie, brilliant” and “a remarkable achievement.” . . . Jessica Treadway says Siobhan Fallon’s new collection of short stories provides “often poignant, sometimes crude, and consistently compelling insights derived from the time she spent in Fort Hood, Texas, during her husband’s two tours of duty in Iraq.” . . . Stefan Collini reviews a new collection of 94-year-old historian Eric Hobsbawm’s writings on Marxism. . . . David Ulin says that a year after J.D. Salinger’s death, much about his life (and his work) remains a mystery, and that a new biography is, perhaps inevitably, “more an extended letter from a fan.”

Monday, January 24th, 2011

Since his death last week, I’ve been thinking about Wilfrid Sheed even more than usual, and through some good soul or other on Twitter, I found this piece he wrote for Commonweal in 1964 about the art of an effective hatchet job. He talks about the genre in general, and lays out six rules for battering a target without generating sympathy for him or her, or looking like a fool yourself. The first two:

1) Hatchet jobs should never run an inch longer than the victim merits. Three sentences are always better than twelve — the length being in itself a form of comment. The critic who goes on swinging after the tree is down draws attention to himself; he becomes overexposed. After all, perhaps he isn’t such a hot writer either. Once the reader’s own sadism has been slaked, the executioner is likely to make him a bit uneasy anyway: “Supposing that was me out there,” he thinks. Prodigious amounts of reader-flattery and I-thou are needed after that to keep him from turning on the critic with an underdog snarl of his own.

2) The complete opposite of Rule 1. It is a mistake to depend too much on short aphoristic dismissals unless your taste in them is absolutely infallible. Length gives at least an impression of lumbering documentation. A bad joke, a heavy-handed insult, give you nothing. The contradictoriness of these first two rules may serve as a warning. Hatcheting is not as easy as it looks.

Saturday, January 22nd, 2011

Friend to this site James Ryerson (more about another project of his soon) has an essay in the New York Times about philosophical novels, and whether philosophy and fiction usefully overlap: “Both disciplines seek to ask big questions, to locate and describe deeper truths, to shape some kind of order from the muddle of the world. But are they competitors — the imaginative intellect pitted against the logical mind — or teammates, tackling the same problems from different angles?”

“It says something about philosophy,” Ryerson writes, “that two of its greatest practitioners, Aristotle and Kant, were pretty terrible writers.” There are a lot of opinions and characters in a relatively short piece. The philosopher Jerry Fodor says that William James didn’t write well, which makes me wonder more about Fodor’s reading abilities. And then there’s philosophically trained William H. Gass talking about his novels: “I don’t pretend to be treating issues in any philosophical sense. I am happy to be aware of how complicated, and how far from handling certain things properly I am, when I am swinging so wildly around.”

Friday, January 21st, 2011

Every March, the online magazine The Morning News hosts the knock-down, drag-out Tournament of Books, wherein 16 works of fiction compete to be called the year’s best. Then, at the end, they play “One Shining Moment” over clips of Franzen getting pumped up before a match or Mantel on a breakaway dunk. I’m excited to be one of the judges for this year’s action. The rest of the judges were announced yesterday, along with the 16 books that will enter the steel cage.

Every March, the online magazine The Morning News hosts the knock-down, drag-out Tournament of Books, wherein 16 works of fiction compete to be called the year’s best. Then, at the end, they play “One Shining Moment” over clips of Franzen getting pumped up before a match or Mantel on a breakaway dunk. I’m excited to be one of the judges for this year’s action. The rest of the judges were announced yesterday, along with the 16 books that will enter the steel cage.

Past winners of the Rooster (the winner theoretically receives a live rooster) are: Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell, The Accidental by Ali Smith, The Road by Cormac McCarthy, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz, A Mercy by Toni Morrison, and Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel.

I would speculate as to what those winners say about this year’s likely favorites, but I should probably recuse myself from that this year. To fuel your own speculation, here are this year’s finalists:

The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake by Aimee Bender

by Aimee Bender

Nox by Anne Carson

by Anne Carson

Bad Marie by Marcy Dermansky

by Marcy Dermansky

Room by Emma Donoghue

by Emma Donoghue

A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan

by Jennifer Egan

Freedom by Jonathan Franzen

by Jonathan Franzen

Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon

by Jaimy Gordon

Bloodroot by Amy Greene

by Amy Greene

Next by James Hynes

by James Hynes

The Finkler Question by Howard Jacobson

by Howard Jacobson

Skippy Dies by Paul Murray

by Paul Murray

Model Home by Eric Puchner

by Eric Puchner

So Much for That by Lionel Shriver

by Lionel Shriver

Super Sad True Love Story by Gary Shteyngart

by Gary Shteyngart

Kapitoil by Teddy Wayne

by Teddy Wayne

Savages by Don Winslow

by Don Winslow

Wednesday, January 19th, 2011

Wilfrid Sheed, one of my literary idols, has died at 80. From the New York Times obituary:

As an avid baseball fan whose boyhood fantasies of diamond glory were dashed at 14 by the onset of polio, Mr. Sheed often said that as a writer he could play any position — a utility man of letters. But novelist was clearly a preferred role.

His gently comic fiction focused on self-perceived variations of himself. His early novels concerned American and English schoolboys (A Middle Class Education in 1960), a writer of inspirational pieces for minor Catholic publications (The Hack, 1963), a bore who learns to live with what he is (Square’s Progress, 1965), the beaten-down denizens of a small liberal magazine (Office Politics, 1966) and a too-brilliant film and theater critic (Max Jamison, 1970).

One of the earliest Backlist pieces for this site was one I wrote about Max Jamison and Essays in Disguise, a collection of Sheed’s inimitable reviews and essays. I also praised the latter book in a feature on the site’s one-year anniversary, in which contributors recommended their favorite out-of-print books.

If you haven’t read him, you should.

Tuesday, January 18th, 2011

Dan Wagstaff runs The Casual Optimist, a blog abut books and book design that I’ve always enjoyed. He was nice enough to ask me several questions about The Second Pass, my favorite authors, and things I’m looking forward to in 2011, among other things. The interview is now up over at his site.

Tuesday, January 18th, 2011

From Light Years by James Salter:

by James Salter:

He wanted one thing, the possibility of one thing: to be famous. He wanted to be central to the human family, what else is there to long for, to hope? Already he walked modestly along the streets, as if certain of what was coming. He had nothing. He had only the carefully laid out luggage of bourgeois life, his scalp beginning to show beneath the hair, his immaculate hands. And the knowledge; yes, he had knowledge. The Sagrada Familia was as familiar to him as a barn to a farmer, the “new towns” of France and England, cathedrals, voussoirs, cornices, quoins. He knew the life of Alberti, of Christopher Wren. He knew that Sullivan was the son of a dancing master, Breuer a doctor in Hungary. But knowledge does not protect one. Life is contemptuous of knowledge; it forces it to sit in the anterooms, to wait outside. Passion, energy, lies: these are what life admires. Still, anything can be endured if all humanity is watching. The martyrs prove it. We live in the attention of others. We turn to it as flowers to the sun.

Monday, January 17th, 2011

I’m using the time this holiday (which happens to be my birthday, too) to make sure you will wake up Tuesday to a fresh site — a new entry on the Shelf, a new Circulating review, a new Backlist entry (I hope), and various things for the blog.

In the meantime, if you’re relatively new to the site and you’re on Twitter, you can follow me there. I post links to new things around here and write about a few other personal interests as well.

Friday, January 14th, 2011

For the last three years, I’ve been lucky enough to spend New Year’s week at a house in Massachusetts with a group of eight to 10 friends, Big Chill-style (minus the funeral and most of the collective self-loathing). One highlight of each visit is a trip to the local library, which is always giving away books that time of year.

For the last three years, I’ve been lucky enough to spend New Year’s week at a house in Massachusetts with a group of eight to 10 friends, Big Chill-style (minus the funeral and most of the collective self-loathing). One highlight of each visit is a trip to the local library, which is always giving away books that time of year.

My two best finds this year were a book and a bookmark. First, the book, To the Happy Few, a selected collection of Stendhal’s letters. I haven’t had time to read many of them yet, but I’m looking forward to digging in. This is the start of a letter he wrote to his sister Pauline on April 10, 1800, when he was 17:

I cannot at all understand your silence, my dear Pauline. What can be the occupations that prevent you from writing to me? Dancing, I would suppose, were we not in Lent. But I’ll wager you one thing: you are thinking to yourself that you must carefully prepare your letter and make a rough draft of it. That’s the stupidest folly that can possess one, for, to have a good epistolary style, one must write exactly what one would say to the person if one saw him, only being careful not to write down repetitions to which, in conversation, a tone of voice or gesture might give some value.

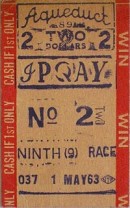

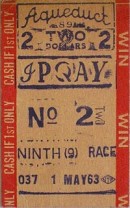

I also picked up The Existential Imagination by Frederick R. Karl and Leo Hamalian. I was thinking about bringing it home for a couple reasons: first, because I’ve found a few other old mass-market paperbacks about existentialism in such places, and it’s a nice mini-collection to have; and secondly, because it was free. The deal was sealed when I noticed what a prior reader had used to mark their place: a beautiful ticket from a horse race at Aqueduct in 1963. As a fan of horse racing, this was hard to resist. I suppose I could have just lifted the ticket and left the book, but as a fan of books, that was unlikely.

I also picked up The Existential Imagination by Frederick R. Karl and Leo Hamalian. I was thinking about bringing it home for a couple reasons: first, because I’ve found a few other old mass-market paperbacks about existentialism in such places, and it’s a nice mini-collection to have; and secondly, because it was free. The deal was sealed when I noticed what a prior reader had used to mark their place: a beautiful ticket from a horse race at Aqueduct in 1963. As a fan of horse racing, this was hard to resist. I suppose I could have just lifted the ticket and left the book, but as a fan of books, that was unlikely.

Thursday, January 13th, 2011

Edmund White chooses his top 10 New York books. I love that he chooses Amis’ Money. Of another book on his list, he writes, “I can think of no other novel that is so agreeable and so devoid of incident.” . . . Levi Stahl has a smart consideration of opening lines in novels, and heretically (but convincingly) says Anna Karenina would have benefited from something different. . . . I recently linked to an appreciation of Barbara Comyns. Now, John Self reviews one of her books, an “eccentric, charming, ambiguous little gem.” . . . George Orwell had some experience with — and some choice words for — people who shop at used bookstores. (Something I happily do myself.) . . . Critic, author, editor, and master anthologizer John Gross died this week at 75. . . . Patrick Brown says the new book by the brains at basketball blog Free Darko is “a work of literature that happens to be about the NBA.” . . . A newly published edition of the Bible includes excerpts of C.S. Lewis’ work throughout. . . . On their new show Portlandia, Fred Armisen and Carrie Brownstein (of Sleater-Kinney fame) ask, “did you read that?”

Edmund White chooses his top 10 New York books. I love that he chooses Amis’ Money. Of another book on his list, he writes, “I can think of no other novel that is so agreeable and so devoid of incident.” . . . Levi Stahl has a smart consideration of opening lines in novels, and heretically (but convincingly) says Anna Karenina would have benefited from something different. . . . I recently linked to an appreciation of Barbara Comyns. Now, John Self reviews one of her books, an “eccentric, charming, ambiguous little gem.” . . . George Orwell had some experience with — and some choice words for — people who shop at used bookstores. (Something I happily do myself.) . . . Critic, author, editor, and master anthologizer John Gross died this week at 75. . . . Patrick Brown says the new book by the brains at basketball blog Free Darko is “a work of literature that happens to be about the NBA.” . . . A newly published edition of the Bible includes excerpts of C.S. Lewis’ work throughout. . . . On their new show Portlandia, Fred Armisen and Carrie Brownstein (of Sleater-Kinney fame) ask, “did you read that?”

Wednesday, January 12th, 2011

Timothy Noah at Slate recently wrote a love letter to the reviews of the New York Times’ Dwight Garner. Noah says, “It’s harder than you might think to produce good writing about bad writing.” I’m not sure it’s harder than producing good writing about good writing, but in any case, Garner is good at every aspect of the game.

Timothy Noah at Slate recently wrote a love letter to the reviews of the New York Times’ Dwight Garner. Noah says, “It’s harder than you might think to produce good writing about bad writing.” I’m not sure it’s harder than producing good writing about good writing, but in any case, Garner is good at every aspect of the game.

It was nice to see Noah’s appreciation, especially since I’ve been meaning to share a few paragraphs from Garner’s take on Timothy Ferriss’ The 4-Hour Body: An Uncommon Guide to Rapid Fat-Loss, Incredible Sex, and Becoming Superhuman, which Noah calls “one of the funniest book reviews I’ve ever read.” It is perhaps an exhibit in the case that bad writing is easier to write about, given the plethora of material it provides and the heavy lifting the excerpts do in entertaining the reader. (Under a tight deadline, would you rather write 1,000 words praising Middlemarch or the same number mocking Going Rogue?) But there’s certainly skill involved in putting it all together and producing your own laughs. A taste:

Everything about Mr. Ferriss’ book declares: This is not your auntie’s self-help book. No muffled “I’m OK — You’re OK” tone here. The vibe is: I’m Superbad, bro, and I have dimples. You’re a mole person who, if you become an angel investor in my books, might someday touch the hem of my Speedo.

In his previous book, The 4-Hour Workweek: Escape 9-5, Live Anywhere, and Join the New Rich (his subtitles are awesome), which was on the hardcover advice best-seller list for more than 75 weeks, he delivered tips like (I’m exaggerating only slightly): hire an overseas virtual assistant for a few bucks an hour and use the extra time to ski in the Andes.

His new one, The 4-Hour Body: An Uncommon Guide to Rapid Fat-Loss, Incredible Sex, and Becoming Superhuman, made its debut at No. 1 on the hardcover advice list on Jan. 2. It’s among the craziest, most breathless things I’ve ever read, and I’ve read Klaus Kinski, Dan Brown and Snooki.

Monday, January 10th, 2011

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Richard Williams admires a biography of the great music archivist Alan Lomax: “The result is an extensive portrait of a brilliant and difficult man who, astonishing as it may now seem, spent most of his career battling the indifference of those in a position to help him preserve the irreplaceable.” . . . Gordon S. Wood writes about Jill Lepore’s most recent book, and about the differing values of symbols and scholarship when it comes to history: “The Tea Partiers are certainly not scholars, but their emotional instincts about the Revolution they are trying to remember on behalf of their cause may be more accurate than Lepore is willing to grant. Popular memory is not history, and that important distinction seems to be the source of the problem with Lepore’s book.” . . . Second Pass contributor Alexander Nazaryan reviews Molotov’s Magic Lantern, Rachel Polonsky’s book about literature and history in Russia: “It is, at heart, a book about books — and, more specifically, about the Russian books that Polonsky so obviously loves and knows so much about, and the fecund Russian soil that the authors of those books mostly loved but sometimes loathed, and, lastly, the blood that has been spilled on that earth by men for whom the power of ideas triumphed over the impermanent domain of flesh.” . . . Adam Kirsch reviews a book about novels based on a series of lectures delivered by Nobel Prize-winner Orhan Pamuk in 2009: “the power of Pamuk’s short book lies less in his theorizing about the novel than in his professions of faith in it.” . . . Gary Rosen reviews James Miller’s Examined Lives, an “earnest, wistful collection of biographical sketches of a dozen pre-eminent ‘lovers of wisdom,’ from Socrates to Nietzsche.” . . . Scott McLemee reviews historian Eric Foner’s “straightforward and painstaking” new book about Abraham Lincoln and slavery.

Richard Williams admires a biography of the great music archivist Alan Lomax: “The result is an extensive portrait of a brilliant and difficult man who, astonishing as it may now seem, spent most of his career battling the indifference of those in a position to help him preserve the irreplaceable.” . . . Gordon S. Wood writes about Jill Lepore’s most recent book, and about the differing values of symbols and scholarship when it comes to history: “The Tea Partiers are certainly not scholars, but their emotional instincts about the Revolution they are trying to remember on behalf of their cause may be more accurate than Lepore is willing to grant. Popular memory is not history, and that important distinction seems to be the source of the problem with Lepore’s book.” . . . Second Pass contributor Alexander Nazaryan reviews Molotov’s Magic Lantern, Rachel Polonsky’s book about literature and history in Russia: “It is, at heart, a book about books — and, more specifically, about the Russian books that Polonsky so obviously loves and knows so much about, and the fecund Russian soil that the authors of those books mostly loved but sometimes loathed, and, lastly, the blood that has been spilled on that earth by men for whom the power of ideas triumphed over the impermanent domain of flesh.” . . . Adam Kirsch reviews a book about novels based on a series of lectures delivered by Nobel Prize-winner Orhan Pamuk in 2009: “the power of Pamuk’s short book lies less in his theorizing about the novel than in his professions of faith in it.” . . . Gary Rosen reviews James Miller’s Examined Lives, an “earnest, wistful collection of biographical sketches of a dozen pre-eminent ‘lovers of wisdom,’ from Socrates to Nietzsche.” . . . Scott McLemee reviews historian Eric Foner’s “straightforward and painstaking” new book about Abraham Lincoln and slavery.

Friday, January 7th, 2011

This search engine is advertised as a way to discover the New York Times bestsellers the week you were born.

This search engine is advertised as a way to discover the New York Times bestsellers the week you were born.

The week I was born (a January week in the mid-’70s), the five top-selling novels were Burr , Gore Vidal’s fictional treatment of the life of Aaron Burr, which had a profound effect on the views of at least one American politician; The Honorary Consul

, Gore Vidal’s fictional treatment of the life of Aaron Burr, which had a profound effect on the views of at least one American politician; The Honorary Consul by Graham Greene; Come Nineveh, Come Tyre

by Graham Greene; Come Nineveh, Come Tyre by Allen Drury, a right-wing fantasy about a liberal president caving to the Soviets, a copy of which is probably somewhere in Glenn Beck’s library; Mary Stewart’s The Hollow Hills, part of a series of novels about the King Arthur legend; and Theophilus North

by Allen Drury, a right-wing fantasy about a liberal president caving to the Soviets, a copy of which is probably somewhere in Glenn Beck’s library; Mary Stewart’s The Hollow Hills, part of a series of novels about the King Arthur legend; and Theophilus North , a fictionalized memoir by Thornton Wilder.

, a fictionalized memoir by Thornton Wilder.

The top two nonfiction books the week I was born are both classics in their fields: Alistair Cooke’s America and The Joy of Sex

and The Joy of Sex .

.

Of course, you can enter any date, so feel free to be less narcissistic and use it for broader research.

Thursday, January 6th, 2011

Jim Hanas has a New Year’s resolution this site can get behind: For a project he’s calling “NBA Minus 50,” he’s going to read (and write about) all 12 fiction nominees for the 1961 National Book Award. The group includes some very familiar titles — To Kill a Mockingbird, Rabbit, Run, and The Violent Bear It Away — but also some obscure titles, like Ceremony in Lone Tree by Wright Morris, Mildred Walker’s The Body of a Young Man, and that year’s winner, The Waters of Kronos by Conrad Richter.

A couple of years ago, on the National Book Awards site, Harold Augenbraum wrote of Richter’s novel:

The book begins with a nod to realism. A man returns to the vicinity of his hometown, which is now under water from its flooding to create a hydroelectric dam (Richter, says the New York Times, “lamented progress”). Though the town is submerged, the graves have been moved to higher ground (hint, hint). The man, John Donner (John Donne? The Donner Party? You tell me.) walks through the cemetery, and when he gets to the other side, he hitches a ride with a man in a wagon, past where the water should be, into the town itself. We quickly realize that we have been thrown backwards in time. Donner is an old man who revisits his childhood. Weird. Intriguing. Thought-provoking. If Proust had written Brigadoon, it would be The Waters of Kronos.

Thursday, January 6th, 2011

James Morrison (aka Caustic Cover Critic) has begun designing and publishing an eclectic mix of books whose copyrights have expired. The one that stood out to me was Eugene Batchelder’s A Romance of the Sea-Serpent, “an 1850 book-length Monty Python-style doggerel poem about a socially aspirant sea serpent.” Morrison quotes David S. Reynolds’ description of the book from an essay about Moby-Dick: “The largest monster in antebellum literature was the kraken depicted in [Batchelder's book], a bizarre narrative poem about a sea serpent that terrorizes the coast of Massachusetts, destroys a huge ship in mid-ocean, repasts on human remains gruesomely with sharks and whales, attends a Harvard commencement (where he has been asked to speak), [and] shocks partygoers by appearing at a Newport ball.” Sign me up. . . . I read Richard Ben Cramer’s massive and entertaining What It Takes, about the 1988 presidential election, a couple of years ago. Ben Smith at Politico writes about the doorstop’s initial chilly reception and eventual fan base, “a case study in how a book enters the canon.” (Via) . . . John Gall shares some work by his talented design students. . . . For the new year, Scott Pack has started a new blog, where he will write about one short story per day. . . . David L. Ulin champions one of my favorite books when I was a kid, The Cricket in Times Square. . . . Tin House has redesigned its home page, its blog, and its everything else.

James Morrison (aka Caustic Cover Critic) has begun designing and publishing an eclectic mix of books whose copyrights have expired. The one that stood out to me was Eugene Batchelder’s A Romance of the Sea-Serpent, “an 1850 book-length Monty Python-style doggerel poem about a socially aspirant sea serpent.” Morrison quotes David S. Reynolds’ description of the book from an essay about Moby-Dick: “The largest monster in antebellum literature was the kraken depicted in [Batchelder's book], a bizarre narrative poem about a sea serpent that terrorizes the coast of Massachusetts, destroys a huge ship in mid-ocean, repasts on human remains gruesomely with sharks and whales, attends a Harvard commencement (where he has been asked to speak), [and] shocks partygoers by appearing at a Newport ball.” Sign me up. . . . I read Richard Ben Cramer’s massive and entertaining What It Takes, about the 1988 presidential election, a couple of years ago. Ben Smith at Politico writes about the doorstop’s initial chilly reception and eventual fan base, “a case study in how a book enters the canon.” (Via) . . . John Gall shares some work by his talented design students. . . . For the new year, Scott Pack has started a new blog, where he will write about one short story per day. . . . David L. Ulin champions one of my favorite books when I was a kid, The Cricket in Times Square. . . . Tin House has redesigned its home page, its blog, and its everything else.

Wednesday, January 5th, 2011

The Millions has an extensive preview of 2011 books, focused mostly on fiction. There’s plenty to read, though it doesn’t jump out at me as a banner year on paper. There are highly anticipated first novels coming from New Yorker favorites Karen Russell and Tea Obreht. Colm Tóibín, Roddy Doyle, E.L. Doctorow, and Jim Shepard are publishing story collections.

The Millions has an extensive preview of 2011 books, focused mostly on fiction. There’s plenty to read, though it doesn’t jump out at me as a banner year on paper. There are highly anticipated first novels coming from New Yorker favorites Karen Russell and Tea Obreht. Colm Tóibín, Roddy Doyle, E.L. Doctorow, and Jim Shepard are publishing story collections.

The only giant on the horizon is David Foster Wallace’s posthumous novel, The Pale King, due in April. Such projects give me — and many others — pause, but like any Wallace fan, I’m more than curious.

Tuesday, January 4th, 2011

Ed Park, author of the novel Personal Days and an editor at The Believer, recently wrote for the New York Times about gargantuan sentences. Several authors throughout history have attempted to write an entire novel as one sentence. Perhaps the most recent is Mathias Énard, whose novel Zone

and an editor at The Believer, recently wrote for the New York Times about gargantuan sentences. Several authors throughout history have attempted to write an entire novel as one sentence. Perhaps the most recent is Mathias Énard, whose novel Zone was recently translated to English. The book is longer than 500 pages. Park points out the technicalities that keep it from qualifying as one long sentence, but it’s close.

was recently translated to English. The book is longer than 500 pages. Park points out the technicalities that keep it from qualifying as one long sentence, but it’s close.

Park writes of the endless-sentence endeavor:

Not many writers have had the nerve to go this route: you’re locked in, committed to a rhythm and a certain claustrophobia. But might the format also be liberating? Joan Didion told The Paris Review in 1978: “What’s so hard about that first sentence is that you’re stuck with it. Everything else is going to flow out of that sentence. And by the time you’ve laid down the first two sentences, your options are all gone.” Sticking to just one sentence, ironically, might keep your options perpetually open.

The article reminded me of one of my favorite long sentences. At just 129 words, it’s a miniscule thing compared to those Park focused on, but I like an excuse to share it (again). It’s from Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff, and comes when Chuck Yeager and other pilots are at a bar in the desert, celebrating his breaking of the sound barrier:

So Pancho served Yeager a big steak dinner and said they were a buncha miserable peckerwoods all the same, and the desert cooled off and the wind came up and the screen doors banged and they drank some more and bawled some songs over the cackling dry piano and the stars and the moon came out and Pancho screamed oaths no one had ever heard before and Yeager and Ridley roared and the old weatherbeaten bar boomed and the autographed pictures of a hundred dead pilots shook and clattered on the frame wires and the faces of the living fell apart in the reflections, and by and by they all left and stumbled and staggered and yelped and bayed for glory before the arthritic silhouettes of the Joshua trees.

Monday, January 3rd, 2011

Over the holidays, I found two fascinating pieces about women who wrote in the first half of the 20th century. The more haunting one — written by Paul Collins for Lapham’s Quarterly — is about Barbara Newhall Follett (at left), who started writing her first novel at the age of eight, sometimes putting down 4,000 words a day:

Over the holidays, I found two fascinating pieces about women who wrote in the first half of the 20th century. The more haunting one — written by Paul Collins for Lapham’s Quarterly — is about Barbara Newhall Follett (at left), who started writing her first novel at the age of eight, sometimes putting down 4,000 words a day:

While her notes to her playmates and family overflowed with warmth, she was absolute in guarding her time to write. Neighboring children who didn’t understand were brusquely dismissed.

“You don’t understand why I have my work to do — because, at this particular time, you have none at all,” she snapped in a letter to a complaining playmate.

As 1923 passed into another year and yet another, she wrote and rewrote her tale of a girl who ventures into the woods and vanishes into nature. Friends, when needed, could always be imagined. “I pretend,” she once explained, “that Beethoven, the two Strausses, Wagner, and the rest of the composers are still living, and they go skating with me.”

The finished novel, The House Without Windows, was published in 1927, when Follett was 13, to much praise. The rest of Follett’s story is too good, strange, and heartbreaking to miss. Collins says, “Her writings, out of print for many decades, only exist today in six archival boxes at Columbia University’s library. Taken together, they are the saddest reading in all of American literature.”

And over at The Awl, Emily Gould champions the work of Barbara Comyns, “born in 1909 in a big house on the Avon, fourth of the six children of a drunk father and an indifferent mother.” Filled with “bizarre and otherworldly detail,” Comyns’ stories, according to Gould, are riveting:

Comyns’ voice has childlike qualities; she looks at everything in the world as though seeing it for the first time. In later books, though, her narrators’ naivety is deployed in order to provoke horror; the gap between what the reader knows and the narrator doesn’t serves to make the reader fascinated and fearful. Often the reader is horrified and amused simultaneously.

Unlike Follett’s work, several of Comyns’ books are easily available, including the greatly titled Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead and The Vet’s Daughter

and The Vet’s Daughter , which NYRB Classics reissued a few years ago.

, which NYRB Classics reissued a few years ago.

Reynolds Price died last week at 77. Of his many, many works, I’ve only read The Surface of Earth

Reynolds Price died last week at 77. Of his many, many works, I’ve only read The Surface of Earth and The Source of Light

, the first two books in a trilogy about the fictional Mayfield family. The New York Times obit said the trilogy “confounded critics.” I read them a long time ago — I remember them being highly stylized (and maybe maudlin), but also affecting.

Geoffrey O’Brien reviews James Kaplan’s biography of Frank Sinatra, which covers

Geoffrey O’Brien reviews James Kaplan’s biography of Frank Sinatra, which covers  Every March, the online magazine The Morning News hosts the knock-down, drag-out Tournament of Books, wherein 16 works of fiction compete to be called the year’s best. Then, at the end, they play

Every March, the online magazine The Morning News hosts the knock-down, drag-out Tournament of Books, wherein 16 works of fiction compete to be called the year’s best. Then, at the end, they play  For the last three years, I’ve been lucky enough to spend New Year’s week at a house in Massachusetts with a group of eight to 10 friends, Big Chill-style (minus the funeral and most of the collective self-loathing). One highlight of each visit is a trip to the local library, which is always giving away books that time of year.

For the last three years, I’ve been lucky enough to spend New Year’s week at a house in Massachusetts with a group of eight to 10 friends, Big Chill-style (minus the funeral and most of the collective self-loathing). One highlight of each visit is a trip to the local library, which is always giving away books that time of year. I also picked up The Existential Imagination by Frederick R. Karl and Leo Hamalian. I was thinking about bringing it home for a couple reasons: first, because I’ve found a few other old mass-market paperbacks about existentialism in such places, and it’s a nice mini-collection to have; and secondly, because it was free. The deal was sealed when I noticed what a prior reader had used to mark their place: a beautiful ticket from a horse race at Aqueduct in 1963. As a fan of horse racing, this was hard to resist. I suppose I could have just lifted the ticket and left the book, but as a fan of books, that was unlikely.

I also picked up The Existential Imagination by Frederick R. Karl and Leo Hamalian. I was thinking about bringing it home for a couple reasons: first, because I’ve found a few other old mass-market paperbacks about existentialism in such places, and it’s a nice mini-collection to have; and secondly, because it was free. The deal was sealed when I noticed what a prior reader had used to mark their place: a beautiful ticket from a horse race at Aqueduct in 1963. As a fan of horse racing, this was hard to resist. I suppose I could have just lifted the ticket and left the book, but as a fan of books, that was unlikely. Edmund White chooses

Edmund White chooses  Timothy Noah at Slate recently wrote

Timothy Noah at Slate recently wrote  Richard Williams

Richard Williams  This

This  James Morrison (aka Caustic Cover Critic) has begun designing and publishing

James Morrison (aka Caustic Cover Critic) has begun designing and publishing  The Millions has

The Millions has  Over the holidays, I found two fascinating pieces about women who wrote in the first half of the 20th century. The

Over the holidays, I found two fascinating pieces about women who wrote in the first half of the 20th century. The