Readers of a certain musical bent will likely be charmed by these prints imagining songs by The Smiths as vintage Penguin paperbacks. . . . A fun interview with Jonathan Lethem about movies: his new book about the cult classic They Live, his opinion of Christopher Nolan’s movies, and which of his novels David Cronenberg has shown interest in bringing to the screen. . . . Patrick Kurp shares more than one piece of wisdom from Marianne Moore in a piece she wrote called “If I Were Sixteen Today” when she was 70. . . . Learn why, “You should avoid the culture pages of the New Yorker if you are a teenage boy already terrified that you’re never going to have sex.” . . . I don’t have any interest in actually reading this, but seeing as how my undefeated fantasy football team is named the Fighting Roger Sterlings, I feel obligated to pass it on. . . . Dinaw Mengestu talks to the Paris Review about his new novel. (“I wanted to show how two people can be attached to each another and still feel completely alienated.”) . . . Not technically book-related, but still amazing: In 1916, a respected engineer and urban planner proposed “A Really Greater New York” in an article for Popular Science. The plan included filling in the East River.

Readers of a certain musical bent will likely be charmed by these prints imagining songs by The Smiths as vintage Penguin paperbacks. . . . A fun interview with Jonathan Lethem about movies: his new book about the cult classic They Live, his opinion of Christopher Nolan’s movies, and which of his novels David Cronenberg has shown interest in bringing to the screen. . . . Patrick Kurp shares more than one piece of wisdom from Marianne Moore in a piece she wrote called “If I Were Sixteen Today” when she was 70. . . . Learn why, “You should avoid the culture pages of the New Yorker if you are a teenage boy already terrified that you’re never going to have sex.” . . . I don’t have any interest in actually reading this, but seeing as how my undefeated fantasy football team is named the Fighting Roger Sterlings, I feel obligated to pass it on. . . . Dinaw Mengestu talks to the Paris Review about his new novel. (“I wanted to show how two people can be attached to each another and still feel completely alienated.”) . . . Not technically book-related, but still amazing: In 1916, a respected engineer and urban planner proposed “A Really Greater New York” in an article for Popular Science. The plan included filling in the East River.

Archives, October, 2010

Thursday, October 28th, 2010

In the Ether

Thursday, October 28th, 2010

A Selection

From The Dark by John McGahern:

You couldn’t be a priest, never now, that was all. You’d never raise anointed hands. You’d drift into the world, world of girls and women, company in gay evenings, exact opposite of the lonely dedication of the priesthood unto death. Your life seemed set, without knowing why, it was fixed, you had no choice. You were a drifter, you’d drift a whole life long after pleasure, but at the end there’d be the reckoning. If you could be a priest you’d be able to enter that choking moment without fear, you’d have already died to longing, you’d have already abandoned the world for that reality, there’d be no confusion. But the night and room and your father and even the hedge around the orchard at home were all confusion, there was no beginning nor end.

Monday, October 25th, 2010

The Beat

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Dwight Garner says that Avi Steinberg’s Running the Books, which recounts the author’s time as a prison librarian in Boston, “gets off to an obnoxious start,” reading mostly like a “hopped-up” gimmick. But according to Garner, the gimmick deepens into something much more: “Mr. Steinberg’s sentences start to pop out at you, at first because they’re funny and then because they’re acidly funny. The book slows down. It blossoms. Mr. Steinberg proves to be a keen observer, and a morally serious one. His memoir is wriggling and alive — as involving, and as layered, as a good coming-of-age novel.” . . . Maile Meloy makes Thomas McGuane’s latest sound like a lot of fun, even if it’s a bit sloppy in squaring all the facts of its fictional world: “As with McGuane’s earlier novels, the rambling plot is sustained because the individual episodes are a pleasure, often farcical and always acutely observed, and because the hero is sympathetic in his dissociated journey.” . . . Patrick Marnham reviews Pedigree, the “lengthy but little-read autobiographical novel” by Georges Simenon, “a Dickensian portrait, with poverty, crime, lunacy, wealth, corruption, and mockery, but a complete absence of Dickensian sentimentality.” . . . Jay Parini has written novels about Tolstoy, Walter Benjamin, and now, Herman Melville. Christopher Benfey admits he dreaded reading this latest, but he comes away mostly impressed. . . . John Self considers a new edition of a 1950s novel in which UK and U.S. astronomers simultaneously discover the “existence of a black cloud in the outer regions of the solar system” that is moving toward Earth. “Gentlemanly panic, tempered by scientific curiosity, ensues.”

Dwight Garner says that Avi Steinberg’s Running the Books, which recounts the author’s time as a prison librarian in Boston, “gets off to an obnoxious start,” reading mostly like a “hopped-up” gimmick. But according to Garner, the gimmick deepens into something much more: “Mr. Steinberg’s sentences start to pop out at you, at first because they’re funny and then because they’re acidly funny. The book slows down. It blossoms. Mr. Steinberg proves to be a keen observer, and a morally serious one. His memoir is wriggling and alive — as involving, and as layered, as a good coming-of-age novel.” . . . Maile Meloy makes Thomas McGuane’s latest sound like a lot of fun, even if it’s a bit sloppy in squaring all the facts of its fictional world: “As with McGuane’s earlier novels, the rambling plot is sustained because the individual episodes are a pleasure, often farcical and always acutely observed, and because the hero is sympathetic in his dissociated journey.” . . . Patrick Marnham reviews Pedigree, the “lengthy but little-read autobiographical novel” by Georges Simenon, “a Dickensian portrait, with poverty, crime, lunacy, wealth, corruption, and mockery, but a complete absence of Dickensian sentimentality.” . . . Jay Parini has written novels about Tolstoy, Walter Benjamin, and now, Herman Melville. Christopher Benfey admits he dreaded reading this latest, but he comes away mostly impressed. . . . John Self considers a new edition of a 1950s novel in which UK and U.S. astronomers simultaneously discover the “existence of a black cloud in the outer regions of the solar system” that is moving toward Earth. “Gentlemanly panic, tempered by scientific curiosity, ensues.”

Friday, October 22nd, 2010

“If my calculations are correct, when this baby hits 88 miles per hour…”

Charles Yu, author of the recently published novel How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe

Charles Yu, author of the recently published novel How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, lists 10 of his favorite books about time travel. He starts with Slaughterhouse-Five, always a good choice. (“Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time.”)

The rest of his list is worth reading, and then there are several compelling additions from people in the comments underneath the piece. One of them is The Technicolor Time Machine by Harry Harrison. Published in 1957, it sounds very Terry Gilliam. Wikipedia sums up its plot:

The narrative revolves around the efforts of a mediocre film director to save his job, his livelihood and just incidentally the studio he works for. To do this, he enlists a mad scientist, the crooked studio owner, a jazz tuba player, a cowboy, two fabulously stupid movie stars, and a real live ocean-crossing Viking. He ends up making history, but in a way he never dreamed of.

A few more that caught my eye: Behold the Man by Michael Moorcock, a short book — controversial, I’m sure — in which someone from 1970 travels back in time to find Jesus and ends up assuming the role of the savior when the facts don’t match what he was expecting to find. (The book has also had, as you can imagine, its share of amazingly ’70s-ish covers: here, here and here, for starters.) Replay

by Ken Grimwood, in which a man keeps going back in time with his memories of the future intact, a la Groundhog Day (which the novel predates).

And Sputnik Caledonia by Andrew Crumey, a story of time travel and alternative history. John Self reviewed the book here, and interviewed Crumey here.

Thursday, October 21st, 2010

In the Ether

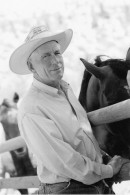

Thomas McGuane’s new novel, Driving on the Rim

Thomas McGuane’s new novel, Driving on the Rim, is just out, and Charles McGrath profiles him for the New York Times: “There’s a view of Montana writing that seems stage-managed by the Chamber of Commerce — it’s all about writers like A. B. Guthrie and Ivan Doig. It used to bother me that nobody had a scene where somebody was delivering a pizza.” . . . Richard Ford’s next novel is going to be set in Canada. And called that, too. . . . Scott Pack recently wrote that, in honor of his 40th birthday, he’s going to blog about “the 40 books that have most moved, delighted, astounded, impressed and entertained me since I emerged screaming in the maternity ward of Rochford Hospital in 1970.” The first two have inspired strong posts: a memoir by Frank Muir and a sci-fi novel Pack read as a boy. . . . By and large, I think book trailers are an enormous waste of time. But I like John Lanchester, and I like this book trailer. Do I like it as a book trailer? Well, the philosophy of all this deserves a separate post sometime. . . . Greil Marcus and Sean Wilentz, each with a book about Bob Dylan recently published, discuss Mr. Zimmerman with James Mustich. . . . If you’re in New York tonight, there’s a Bookslut event in Brooklyn that sounds like fun. . . . Alexander Chee writes about teaching the graphic novel, and which ones he taught: “[I]n my experience over the years, there are few things more politically dangerous within an English Department than teaching something popular with students.” . . . The Millions links to a sign of the times in a Barnes & Noble store.

Thursday, October 14th, 2010

Behind the Booker Scenes

In the wake of the National Book Awards announcement yesterday, Sam Anderson says, “I still believe that Freedom is a great novel; I still want to eat some of its sentences with tiny little corn holders.” But he doesn’t mind that it was left off the list of nominees.

In the wake of the National Book Awards announcement yesterday, Sam Anderson says, “I still believe that Freedom is a great novel; I still want to eat some of its sentences with tiny little corn holders.” But he doesn’t mind that it was left off the list of nominees.

He also links to an addictive read: a 2008 piece in the Guardian, in which one Booker Prize judge for every year since 1969 discusses the voting process for the year they served. It’s full of gossip, candid enthusiasms and regrets, and thoughts about the value (or lack thereof) of literary prizes. It’s also a good way to trip over some recommendations you might not otherwise find.

Beryl Bainbridge, who judged in 1977, wrote:

All I can remember of the final meeting is that I got terribly tired, I literally sank lower and lower under the table. Brendan Gill, who I thought was American, went towards the balcony saying he was going to throw himself off, he was so fed up. Philip Larkin was completely silent most of the time. Nobody dared say a word to him and he never said a word back.

Paul Bailey (1982) wrote, “There are many things I regret doing, and being a judge for the Booker prize is one of them.” Noting a later snub that other judges did as well, but with more venom, Bailey said, “A wonderful book such as Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Blue Flower was completely ignored, and I hope the judges for 1995 are blushing now to be reminded of their grotesque oversight.”

Jason Cowley (1997) echoed the feelings of another judge, Ruth Rendell, when he said, “I often think that I’ve never quite recovered from my experience of being a judge. I began the year as an enthusiastic and engaged reader and reviewer of contemporary fiction, and ended it much more interested in non-fiction and narrative journalism.”

And Hilary Mantel, who served in 1990, said, “I’m glad I was a Booker judge relatively early in my career. It stopped me thinking that literary prizes are about literary value. Even the most correct jury goes in for horsetrading and gamesmanship, and what emerges is a compromise.” Mantel won the prize last year for Wolf Hall. Given the raft of other awards it’s won, I’m not sure that particular Booker was a compromise.

Mantel, and more than one other judge, believes the all-time best winner of the Booker is The Siege of Krishnapur by J. G. Farrell, making it the second novel of Farrell’s I’m now eager to read. Better get on that.

Fay Weldon’s account of the 1983 voting is worth reading in full. I’ll leave you to it.

Wednesday, October 13th, 2010

NBA Nominees Announced

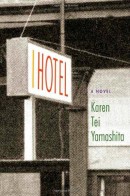

The National Book Award finalists have been announced. In fiction, the lead story will probably be the absence of Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom. The other news is the presence of two small-press titles: I Hotel

The National Book Award finalists have been announced. In fiction, the lead story will probably be the absence of Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom. The other news is the presence of two small-press titles: I Hotel by Karen Tei Yamashita and Lord of Misrule

by Jaimy Gordon. Of the two, Lord of Misrule seems particularly surprising — Gordon’s novel was published by McPherson & Company, and it’s set at a run-down horse track in West Virginia. Sounds like something I might really enjoy.

I Hotel was published by Coffee House Press. Publishers Weekly said that Yamashita “strings together a stunningly complete vision of San Francisco’s Asian American community in the late 1960s and early ’70s, using the titular inn as a meeting point for ten loosely-connected novellas, each covering a single year.” That PW review concluded with this: “with varied commingling of voices and formats (stream-of-consciousness, slangy first person, quotes, dossiers, academic papers, even written-out choreography), the narrative reads like a collection of primary sources. Though it isn’t for everyone, this powerful, deeply felt, and impeccably researched fiction is irresistibly evocative and overwhelming in every sense.”

The nominees for fiction and nonfiction are below. For other categories, visit the NBA site (which appears to be down at the moment).

Fiction:

Parrot and Olivier in America by Peter Carey

Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon

Great House by Nicole Krauss

So Much for That by Lionel Shriver

I Hotel by Karen Tei Yamashita

Nonfiction:

Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea by Barbara Demick

Cultures of War: Pearl Harbor, Hiroshima, 9-11, Iraq by John W. Dower

Just Kids by Patti Smith

Secret Historian: The Life and Times of Samuel Stewar by Justin Spring

Every Man in This Village Is a Liar: An Education in War by Megan K. Stack

Wednesday, October 13th, 2010

In the Ether

Lane Smith writes a charming (and charmingly illustrated) post about writing his new children’s book, It’s a Book

Lane Smith writes a charming (and charmingly illustrated) post about writing his new children’s book, It’s a Book, which teaches children about that non-digital oddity. Sadly, Smith scrapped the hilarious character at left because, understandably, he didn’t want anyone to think he was making fun of a goofy child. The post includes thoughts about Buster Keaton and the spatial concerns of comedy, porkpie hats, and a mini-history of the jackass as a character in children’s literature. Read it. . . . Speaking of the young, Jill Lepore, reliably entertaining and informative, writes about a new round of books explaining sex to children and the history of the genre. . . . Howard Jacobson has won the Booker Prize for his novel The Finkler Question

, which just went on sale in the U.S. Claire Armitstead says Jacobson’s win is overdue, but that, “many of his fans [will suspect] that, like Margaret Atwood and Ian McEwan before him, he didn’t break the jinx with his best novel.” The Guardian profiled Jacobson in August, and the same paper recently ran an essay by him about the history of, and importance of, humor in novels. . . . Andrew Seal shares a list of books that Theodore Dreiser kept on his shelves under the group title “Library of American Realism.” . . . Levi Stahl, fan of scary stories, welcomed in “October Country” last week, and it seems that this month at his terrific blog will be dedicated to literary frights. . . . Rohan Maitzen admires Elizabeth Hardwick’s confidence, and shares several excerpts from her work.

Tuesday, October 12th, 2010

Party Time

On Wednesday, Nov. 10, The Second Pass will venture out into the world for its first event: a reading and party at the terrific Melville House Bookstore in Brooklyn. If you’re in the New York area, I hope you can join us.

The reading portion of the night will involve brief readings from works in progress by four Second Pass contributors:

Carlene Bauer

The author of the memoir Not That Kind of Girl, Carlene has written for Salon, Slate, n+1, the New York Times Magazine, and several other publications.

Will Blythe

The author of To Hate Like This Is to Be Happy Forever, a personal account of the storied North Carolina-Duke basketball rivalry, Will is a widely published critic and journalist whose work regularly appears in the New York Times Book Review, among many other places.

Maud Newton

For more than eight years, Maud has maintained her very popular, eponymous literary blog. She is also a widely published critic and essayist, and the winner of the 2009 Narrative Prize for an excerpt from her novel-in-progress.

Jason Zinoman

A theater critic for the New York Times, Jason is at work on a book about horror movies in the 1970s and the birth of the modern genre. His work has appeared, among other places, in Slate and Vanity Fair, for which he wrote about horror movies in 2008.

The readings will conclude with an entertaining excerpt from a largely forgotten work, in keeping with the site’s preoccupations, presented by Lauren Kaminsky.

The night will start at 7:30, and it will include wine, snacks, plenty of time for socializing, perhaps a few people in blazers, no smoking indoors, and, most importantly, a chance for me to meet some of you and thank you in person for supporting the site. I hope you can make it.

Wednesday, Nov. 10

7:30 p.m.

Melville House

145 Plymouth St. in DUMBO (F to York; A/C to High St./Brooklyn Bridge)

Tuesday, October 12th, 2010

Oh, the Wheel in the Sky Keeps On Turnin’

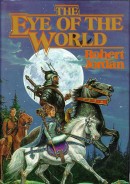

I’m hard-pressed to think of something I’m less likely to read than Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series. Dostoevsky in the original Russian? The entire United States tax code? Currently spanning 13 books, most of them between 700 and 1,000 pages, the Wheel of Time tells a fantastical story that sounds part Bible, part Tolkien, part Tatooine: the usual stew of nerd influences. The books have elegant titles like The Path of Daggers and Knife of Dreams.

I’m hard-pressed to think of something I’m less likely to read than Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series. Dostoevsky in the original Russian? The entire United States tax code? Currently spanning 13 books, most of them between 700 and 1,000 pages, the Wheel of Time tells a fantastical story that sounds part Bible, part Tolkien, part Tatooine: the usual stew of nerd influences. The books have elegant titles like The Path of Daggers and Knife of Dreams.

In the new issue of The Believer, Zach Baron writes about the Wheel of Time, and about the effort, after Jordan’s death in 2007, to find a writer to finish the series. A piece:

Real-life combat experience is something that Jordan, a former helicopter gunner (he claimed to have once shot a rocket-propelled grenade out of midair), shared with Tolkien, who witnessed all but one of his closest friends die in World War I. But where the don of modern fantasy boasted a dusty, Oxford-certified facility with language, philology, and the Middle Ages, Jordan made himself over after Vietnam in the classic mode of the American genre-fiction author. A bearded man with a penchant for elaborate canes, chunky rings, and comical hats, he favored the look of a Southern general. He admitted to being a Freemason. At Q&A sessions, he would not hesitate to interrupt a small child’s incorrect pronunciation of a tertiary character’s name. He wrote the series for which he became famous in an old carriage house cluttered with swords, axes, crossbows, spears, knives, and a human skeleton.

Tuesday, October 12th, 2010

In the Ether

I had no idea there was such a variety of looks for phone books. Astonishing. . . . If you’re looking for the quickest way to become familiar with literature’s newest Nobel winner, the Guardian lists his five most essential novels. This, about the 1977 novel Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter, made me laugh: “The plot is loosely based on the story of Vargas Llosa’s own first marriage, at the age of 19, to the then 32-year-old Julia Urquidi, who was indeed his aunt by marriage. Urquidi later gave a rather different account of her relationship with Vargas Llosa in a memoir, Lo que Varguitas no dijo (What Little Vargas Didn’t Say).” . . . A.N. Devers goes looking for Edgar Allan Poe’s house, which is inside the boundaries of the oldest housing projects in Baltimore: “Our romantic need to idealize historic places presents a particular challenge for writers’ homes, for so many of our best writers lived in obscurity or led notoriously dysfunctional lives.” . . . Ellen Handler Spitz reads a new edition of the Brothers Grimm, and wonders why anyone would suggest that children should be “protected” from their tales. . . . The New Yorker’s Book Bench starts a new series of interviews with book designers, about specific books. First up: Rodrigo Corral on his cover for Gary Shteyngart’s latest. . . . A few translators respond to a series of recent posts by Lydia Davis, and then Davis responds back in the comments. Got that? . . . John Eklund considers the best way to shelve biographies, and then lists several notable bios being published by Yale this season.

I had no idea there was such a variety of looks for phone books. Astonishing. . . . If you’re looking for the quickest way to become familiar with literature’s newest Nobel winner, the Guardian lists his five most essential novels. This, about the 1977 novel Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter, made me laugh: “The plot is loosely based on the story of Vargas Llosa’s own first marriage, at the age of 19, to the then 32-year-old Julia Urquidi, who was indeed his aunt by marriage. Urquidi later gave a rather different account of her relationship with Vargas Llosa in a memoir, Lo que Varguitas no dijo (What Little Vargas Didn’t Say).” . . . A.N. Devers goes looking for Edgar Allan Poe’s house, which is inside the boundaries of the oldest housing projects in Baltimore: “Our romantic need to idealize historic places presents a particular challenge for writers’ homes, for so many of our best writers lived in obscurity or led notoriously dysfunctional lives.” . . . Ellen Handler Spitz reads a new edition of the Brothers Grimm, and wonders why anyone would suggest that children should be “protected” from their tales. . . . The New Yorker’s Book Bench starts a new series of interviews with book designers, about specific books. First up: Rodrigo Corral on his cover for Gary Shteyngart’s latest. . . . A few translators respond to a series of recent posts by Lydia Davis, and then Davis responds back in the comments. Got that? . . . John Eklund considers the best way to shelve biographies, and then lists several notable bios being published by Yale this season.

Monday, October 11th, 2010

The Beat

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Douglas Brinkley raves about Ron Chernow’s new biography of George Washington: “an epic, cradle-to-grave biography destined to win a slew of book awards. A Brooklyn native best known for his brilliant studies of Alexander Hamilton and John D. Rockefeller, Chernow displays a breadth of knowledge about Washington that is nothing short of phenomenal.” . . . Jill Lepore counters that enthusiasm, writing, “Chernow’s aim is to make of Washington something other than a ‘lifeless waxwork,’ an ‘impossibly stiff and wooden figure, composed of too much marble to be quite human.’ That has been the aim of every Washington biographer, and none of them have achieved it.” Lepore finds plenty of interest in Chernow’s book, but feels the final product suffers from applying modern-day context to Washington’s era: “Washington: A Life is a prodigious biography, expertly narrated and full of remarkable detail. But it is a psychological profile of a man who lived and died long before our psychological age, a romantic portrait of a man who was not a Romantic.” . . . Todd Gitlin says the Cold War may be over, but John le Carré’s ” flair for the gut-wrenching drama of betrayed honor” is strong as ever: “He is professionally interested in how hard it is to clean dirty hands, and his sympathies are always with those who make the effort, even if they are doomed.” . . . Amy Benfer reviews Myla Goldberg’s new novel, in which a grown woman reconsiders the role she may have had in the disappearance of a friend during childhood. . . . Allen Barra reviews Jane Leavy’s new biography of Mickey Mantle: “[Leavy] records Mantle’s sins and achievements with the diligence of a first-rate reporter, never losing sight of what drew her to Mickey as a fan in the first place.” . . . Stephen Hawking once left the door open for the existence of God. Peter Galison says Hawking’s latest argues that science doesn’t need God to complete its picture. . . . Russell Stannard’s new book, The End of Discovery, is meant, in part, as a response to books like Hawking’s. The Economist says a response is good idea, but that Stannard’s is “unsatisfactory . . . rushed and lumpy.”

Douglas Brinkley raves about Ron Chernow’s new biography of George Washington: “an epic, cradle-to-grave biography destined to win a slew of book awards. A Brooklyn native best known for his brilliant studies of Alexander Hamilton and John D. Rockefeller, Chernow displays a breadth of knowledge about Washington that is nothing short of phenomenal.” . . . Jill Lepore counters that enthusiasm, writing, “Chernow’s aim is to make of Washington something other than a ‘lifeless waxwork,’ an ‘impossibly stiff and wooden figure, composed of too much marble to be quite human.’ That has been the aim of every Washington biographer, and none of them have achieved it.” Lepore finds plenty of interest in Chernow’s book, but feels the final product suffers from applying modern-day context to Washington’s era: “Washington: A Life is a prodigious biography, expertly narrated and full of remarkable detail. But it is a psychological profile of a man who lived and died long before our psychological age, a romantic portrait of a man who was not a Romantic.” . . . Todd Gitlin says the Cold War may be over, but John le Carré’s ” flair for the gut-wrenching drama of betrayed honor” is strong as ever: “He is professionally interested in how hard it is to clean dirty hands, and his sympathies are always with those who make the effort, even if they are doomed.” . . . Amy Benfer reviews Myla Goldberg’s new novel, in which a grown woman reconsiders the role she may have had in the disappearance of a friend during childhood. . . . Allen Barra reviews Jane Leavy’s new biography of Mickey Mantle: “[Leavy] records Mantle’s sins and achievements with the diligence of a first-rate reporter, never losing sight of what drew her to Mickey as a fan in the first place.” . . . Stephen Hawking once left the door open for the existence of God. Peter Galison says Hawking’s latest argues that science doesn’t need God to complete its picture. . . . Russell Stannard’s new book, The End of Discovery, is meant, in part, as a response to books like Hawking’s. The Economist says a response is good idea, but that Stannard’s is “unsatisfactory . . . rushed and lumpy.”

Friday, October 8th, 2010

A Selection

From Bartleby, the Scrivener by Herman Melville:

Revolving all these things, and coupling them with the recently discovered fact that he made my office his constant abiding place and home, and not forgetful of his morbid moodiness; revolving all these things, a prudential feeling began to steal over me. My first emotions had been those of pure melancholy and sincerest pity; but just in proportion as the forlornness of Bartleby grew and grew to my imagination, did that same melancholy merge into fear, that pity into repulsion. So true it is, and so terrible, too, that up to a certain point the thought or sight of misery enlists our best affections; but, in certain special cases, beyond that point it does not. They err who would assert that invariably this is owing to the inherent selfishness of the human heart. It rather proceeds from a certain hopelessness of remedying excessive and organic ill. To a sensitive being, pity is not seldom pain. And when at last it is perceived that such pity cannot lead to effectual succor, common sense bids the soul be rid of it. What I saw that morning persuaded me that the scrivener was the victim of innate and incurable disorder. I might give alms to his body; but his body did not pain him; it was his soul that suffered, and his soul I could not reach.

Thursday, October 7th, 2010

In the Ether

I’m planning to make this a daily feature. Here’s hoping.

Mario Vargas Llosa has won the Nobel Prize in Literature. . . . Daniel Kalder marvels at the length of time it took Dostoevsky to move from “cause celebre” to “bad joke” among the Russian literati in 1846: 15 days. . . . Michael Savitz writes about making a living by taking a laser scanner into bookstores and searching for treasure. (“One man’s trash is, of course, nearly always another man’s trash.”) . . . Brock Clarke, whose novel Exley was recently reviewed here, writes about the first time he read Frederick Exley’s cultishly beloved A Fan’s Notes. (“He had made it, even though he was a loser, or maybe because he was a loser, or maybe the book itself was proof that he wasn’t a loser after all.”) . . . Rohan Maitzen reads Gone With the Wind for the 32nd time (!!), and considers “whether to keep the book on my shelf or to hide it away, to own or disown it.” . . . Mark Athitakis addresses Joyce Carol Oates, Cormac McCarthy, and the subject of sentimentality. It’s a thorny word that I’ve been meaning to write about (in a way) for a while. This is more inspiration. . . . A non-book link: Wes Anderson lists his favorite movies from the Criterion Collection.

Mario Vargas Llosa has won the Nobel Prize in Literature. . . . Daniel Kalder marvels at the length of time it took Dostoevsky to move from “cause celebre” to “bad joke” among the Russian literati in 1846: 15 days. . . . Michael Savitz writes about making a living by taking a laser scanner into bookstores and searching for treasure. (“One man’s trash is, of course, nearly always another man’s trash.”) . . . Brock Clarke, whose novel Exley was recently reviewed here, writes about the first time he read Frederick Exley’s cultishly beloved A Fan’s Notes. (“He had made it, even though he was a loser, or maybe because he was a loser, or maybe the book itself was proof that he wasn’t a loser after all.”) . . . Rohan Maitzen reads Gone With the Wind for the 32nd time (!!), and considers “whether to keep the book on my shelf or to hide it away, to own or disown it.” . . . Mark Athitakis addresses Joyce Carol Oates, Cormac McCarthy, and the subject of sentimentality. It’s a thorny word that I’ve been meaning to write about (in a way) for a while. This is more inspiration. . . . A non-book link: Wes Anderson lists his favorite movies from the Criterion Collection.