On its Twitter feed, the London Review called this site “oddly mesmerizing,” and I couldn’t agree more.

Archives, July, 2010

Thursday, July 29th, 2010

Best Magazine Articles Ever

Here is a continually updated list of the best magazine articles ever written. It’s already getting a bit unwieldy, with more and more suggestions of things that haven’t exactly passed the test of time, but it’s still a great browsing tool. I was happy to see that someone had submitted Edwin Dobb’s “A Kiss is Still a Kiss (Even if the Sex is Postmodern and the Romance Problematic),” from the February 1996 issue of Harper’s. I remember liking that a lot when it was first published. I’ll have to re-read and see how it holds up.

Then there’s Gary Wolf’s 1995 profile of Ted Nelson for Wired. Nelson, the inventor of hypertext, was working on a massive project called Xanadu. The piece begins:

I said a brief prayer as Ted Nelson—hypertext guru and design genius—took a scary left turn through the impolite traffic on Marin Boulevard in Sausalito. Nelson’s left hand was on the wheel, his right rested casually on the back of the front seat. He arched his neck and looked in my direction so as to be clearly heard. “I’ve been compiling a catalog of driving maneuvers,” he said. “It’s one of my unfinished projects.”

Nelson is a pale, angular, and energetic man who wears clothes with lots of pockets. In these pockets he carries an extraordinary number of items. What cannot fit in his pockets is attached to his belt. It is not unusual for him to arrive at a meeting with an audio recorder and cassettes, video camera and tapes, red pens, black pens, silver pens, a bulging wallet, a spiral notebook in a leather case, an enormous key ring on a long, retractable chain, an Olfa knife, sticky notes, assorted packages of old receipts, a set of disposable chopsticks, some soy sauce, a Pemmican Bar, and a set of white, specially cut file folders he calls “fangles” that begin their lives as 8 1/2-by-11-inch envelopes, are amputated en masse by a hired printer, and end up as integral components in Nelson’s unique filing system. This system is an amusement to his acquaintances until they lend him something, at which point it becomes an irritation. “If you ask Ted for a book you’ve given him,” says Roger Gregory, Nelson’s longtime collaborator and traditional victim, “he’ll say, ‘I filed it, so I’ll buy you a new one.’” For a while, Nelson wore a purple belt constructed out of two dog collars, which pleased him immensely, because he enjoys finding innovative uses for things.

Tuesday, July 27th, 2010

Booker Field Down to 13

The 13 longlist finalists for this year’s Booker Prize have been announced. Three of them have been reviewed on The Second Pass (links where appropriate in the list below), and two others have already been assigned for review this fall, when the books are published in the U.S.

I would put my money on Andrea Levy.

The list:

Parrot and Olivier in America by Peter Carey

Room by Emma Donoghue

The Betrayal by Helen Dunmore

In a Strange Room by Damon Galgut

The Finkler Question by Howard Jacobson

The Long Song by Andrea Levy

C by Tom McCarthy

The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet by David Mitchell

February by Lisa Moore

Skippy Dies by Paul Murray

Trespass by Rose Tremain

The Slap by Christos Tsiolkas

The Stars in the Bright Sky by Alan Warner

Tuesday, July 27th, 2010

The Beat

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

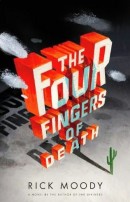

Rick Moody’s kitschy latest is built around a 600-page sci-fi novel within a novel. Sam Sacks shakes his head: “If nothing else, The Four Fingers of Death provides further evidence for the inverse relationship between literary theory and literary quality. As a ‘project’—that’s what the author calls the book in his acknowledgments—it succeeds; as a novel, it’s harebrained and largely unreadable.” . . . Colm Toibin praises Wendy Moffat’s “well-written, intelligent, and perceptive” biography of E. M. Forster, which addresses the writer’s homosexuality. “She uses the sources for our knowledge of Forster’s sexuality, including letters and diaries, without reducing the mystery and sheer individuality of Forster, without making his sexuality explain everything.” . . . David Greenberg assesses a new biography of the 28th President of the United States: “Woodrow Wilson is too authoritative and independent to be reduced to the gadfly position of contrarianism: it is a judicious, penetrating measure of the man and his achievements and it should stand as the best full biography of Wilson for many years.” . . . Jessa Crispin reviews a new co-authored book about the prehistoric roots of human sexuality: “[Though the authors] claim they are not out to make the hunter-gatherer way of life sound more ‘noble,’ that is exactly what they do. Their anthropology sections are basically cut-and-paste jobs, and they leave out any of the dark stuff. Complex social and sexual systems are reduced to a paragraph, sometimes a sentence, making every society they mention sound like a sexy utopia.” . . . Matt Zoller Seitz examines the “psychological evolution” of George Carlin, as told in two recent books about the comic.

Rick Moody’s kitschy latest is built around a 600-page sci-fi novel within a novel. Sam Sacks shakes his head: “If nothing else, The Four Fingers of Death provides further evidence for the inverse relationship between literary theory and literary quality. As a ‘project’—that’s what the author calls the book in his acknowledgments—it succeeds; as a novel, it’s harebrained and largely unreadable.” . . . Colm Toibin praises Wendy Moffat’s “well-written, intelligent, and perceptive” biography of E. M. Forster, which addresses the writer’s homosexuality. “She uses the sources for our knowledge of Forster’s sexuality, including letters and diaries, without reducing the mystery and sheer individuality of Forster, without making his sexuality explain everything.” . . . David Greenberg assesses a new biography of the 28th President of the United States: “Woodrow Wilson is too authoritative and independent to be reduced to the gadfly position of contrarianism: it is a judicious, penetrating measure of the man and his achievements and it should stand as the best full biography of Wilson for many years.” . . . Jessa Crispin reviews a new co-authored book about the prehistoric roots of human sexuality: “[Though the authors] claim they are not out to make the hunter-gatherer way of life sound more ‘noble,’ that is exactly what they do. Their anthropology sections are basically cut-and-paste jobs, and they leave out any of the dark stuff. Complex social and sexual systems are reduced to a paragraph, sometimes a sentence, making every society they mention sound like a sexy utopia.” . . . Matt Zoller Seitz examines the “psychological evolution” of George Carlin, as told in two recent books about the comic.

Monday, July 26th, 2010

“Oh god the pomposity”

I have made my low opinion of Don DeLillo’s White Noise known around here and other places, so I was particularly happy to find this post by Alex Abramovich at the London Review of Books blog. It turns out that The Strand in New York (on a short list of my favorite spots in the world) inherited many books from the recently departed experimental novelist David Markson. Abramovich details some of his finds, but also shares how he knew to browse for them:

I’d heard about the haul from Jeff Severs, who teaches at the University of British Columbia. He’d heard about it from a student who’d stumbled on Markson’s copy of Don DeLillo’s White Noise. ‘my copy of white noise apparently used to belong to david markson (who i had to look up),’ the student had written.

he wrote some notes in the margin: a check mark by some passages, ‘no’ by other, ‘bullshit’ or ‘ugh get to the point’ by others. i wanted to call him up and tell him his notes are funny, but then i realized he DIED A MONTH AGO. bummer.

‘That’s amazing,’ Jeff had replied. ‘Did he write his name in the front or something? Did you buy it secondhand recently – as in, his family sold off his library?’

yeah he wrote his name inside the front cover and the cashiers at the strand said they have his whole collection. favorite comments: ‘oh god the pomposity, the bullshit!’, ‘oh i get it, it’s a sci-fi novel!’ and ‘big deal’.

Monday, July 26th, 2010

Nuclear Bombs and iPhones

Andrew Seal expresses irritation at the Gary Shteyngart essay I linked to last week, in which Shteyngart bemoaned the effect of social media and other technology on his readerly attention span. Seal writes:

Andrew Seal expresses irritation at the Gary Shteyngart essay I linked to last week, in which Shteyngart bemoaned the effect of social media and other technology on his readerly attention span. Seal writes:

I think a number of American writers—New Yorkers, mostly—have either decided or come to some unspoken and maybe half-conscious consensus that the societal changes being brought about by social media are as encompassing and as threatening to the fundamentals of something which used to be called human nature as the threat of nuclear war was in the 1950s. [. . .] In both cases, what is being described as a threat is a putatively immersive environment—in the 1950s, the fear of nuclear war; today, the distraction of social media—which is pushing humanity (seemingly as a species, although in real terms the most threatened are the most advanced societies) toward a point of crisis where what has been driven into latency or rarity—in the 1950s, the “dignity of man” or, articulated in more practical terms, the feeling of agency and choice; today, attention, which is often articulated again in practical terms either as genuine connectedness with other people or the ability to read dense works of literature—might in fact become irrecoverably lost.

Later, he adds:

For what is Shteyngart saying, really? That he checks his iPhone too often? He says, “I don’t know how to read anymore. I can only read 20 or 30 words at a time before taking out my iPhone and caressing it and snuggling with it.” May I suggest that before he had an iPhone, like most readers, his mind might have wandered momentarily every “20 or 30 words”—not to an iPhone screen, of course, but to some “interior” distraction? Do iPhones and the like really produce distraction, or do they just give a single physical destination for it?

I left a comment underneath the post, but I’ve continued thinking about it and figured I would bring the issue here, in case anyone wishes to join in. On the one hand, I don’t like to pass judgment about large cultural shifts when the upshot is simply Things Used To Be Better. Partly this is because a great many things, in fact, used to be worse, and partly because I too often feel like a grumpy 86-year-old when I’m 50 years younger than that. But on the other, larger hand, I don’t think it’s just grumpiness that might cause someone to be alarmed by the potential effects of social media. There are many of those potential effects (not all of them bad, of course), but the focus for Shteyngart and Seal is attention span.

What surprises me is how quickly Seal equates interior distractions and iPhones before moving on. Shteyngart and others might sometimes overstate the peril of the human soul, but I think Seal’s post understates the nature of the shift represented by social technologies. Picture yourself sitting somewhere—and it doesn’t have to be idyllic; let’s say a crowded coffee shop in the middle of Manhattan—and you feel an “interior distraction.” The distraction originates, presumably, in some thought or subtle sensory perception of your own. (If someone, say, stepped on your foot or spilled a hot drink on you or started shouting to all the gathered customers about Jesus, that would be an external distraction.) You follow the distraction to its conclusion and return to your book or other work.

The iPhone, I hope we can agree, is an external distraction, and I think immediately of two traits that therefore make it distinct: It’s an intrusion created and controlled by someone else, rather than by your own thought process, however random that process might be; and it easily leads to other distractions. Seal doesn’t appear interested in distinguishing between internal and external distractions. (I realize his thoughts could be elaborated on to dispel this notion.) To me—and maybe this is where 36 actually is very old these days; I’m not sure of Seal’s age, but I think he’s a bit younger—distinguishing between them is crucial. And what deepens that difference is that our external distractions are now fully portable. A call on the iPhone could easily lead to an hour or several of texting or surfing the web on the same device. When Seal writes that Shteyngart’s mind might have “wandered momentarily” before iPhones, he ignores the fact that our wanderings are constant now, almost never momentary.

This does not mean that humanity is doomed. But it does mean something. To see much younger generations use their cell phones, Facebook, et al., is to see people who do have a different relationship to reading and writing. I find that hard to ignore, whatever its consequences—perhaps those consequences will end up being thoroughly beneficial, but my inner octogenarian seriously doubts that. In any case, it’s fair to say that it’s an issue worth exploring. Even Seal’s analogy—the nuclear age—gives me pause. Is it possible to say that the creation and proliferation of nuclear weapons did nothing to collective human psychology and behavior?

Monday, July 26th, 2010

A Deep Devotion to Standards

Mary E. Laur, an editor at the University of Chicago Press and part of the team that puts together new editions of The Chicago Manual of Style, writes about the reactions she gets from readers:

Mary E. Laur, an editor at the University of Chicago Press and part of the team that puts together new editions of The Chicago Manual of Style, writes about the reactions she gets from readers:

More often than not, people who hear that I work on the Manual—even those from outside the worlds of academia and publishing—instantly recognize the title, a rare treat for an editor in scholarly publishing. Sometimes they tell me stories of college days spent wrestling with proper footnote format or of interoffice battles over comma use, both of which likely involved recourse to the Manual. Inevitably, they ask me questions. Their curiosity increasingly centers on the broad issues that preoccupy those of us on the revision team, such as how changes wrought by technology affect everything from editing processes to citation style. But the question I still field most frequently concerns a matter of much smaller scale:

After a period or other sentence-ending punctuation mark, should I leave one space or two?

The Manual’s answer to this question is simple enough—one—but I have learned from experience that everyone who asks it wants me to say two. Often I suspect they know my answer in advance and hope to pick a fight with me. [. . .]

Although I still puzzle over the widespread attachment to this particular convention, I have gradually come to see it as a manifestation of the same force that underlies the long-term success of the Manual: a deep devotion to standards in the realm of the written word. [. . .] For all the hand-wringing about our imminent decline into a text-messaging, “LOL” culture devoid of standards, I see evidence every day that people still care about getting the details of their writing right.

This is heartening, given that I’m a hand-wringer myself. In fact, more on that in the next blog post…

Friday, July 23rd, 2010

A Note About a Note

A well-intentioned lie on the blog yesterday: The Backlist section will now be updated Monday, not today. I know you will somehow manage to get on with your life and enjoy your weekend.

Thursday, July 22nd, 2010

A Few Notes

Just some housekeeping and reminders on this Thursday afternoon: If you’d like to follow the Second Pass’ RSS feed, you can do so here. You can also follow me on Twitter here. The site’s index has been brought up to date, if you care to search through the archives a bit. The Shelf has been updated this week, and will continue to be, hopefully at a better pace than recent weeks.

Tomorrow will bring an overdue update to the Backlist section. Thanks for continuing to visit during the dog days of summer — lots of fun things planned for the coming days, weeks, and months.

Thursday, July 22nd, 2010

“It’s no fun hearing a story that’s really meant to be read.”

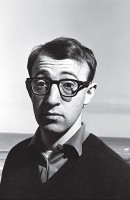

Woody Allen was recently convinced to record audiobooks for his four collections of humorous essays. Between this, Andrew Wylie’s foray into e-books, and the recent news from Amazon, I was worried that old-fashioned cranks like me, who believe in reading books on paper, were finally extinct. I mean, if Woody Allen is on board? But thankfully, Allen brought the crank:

Woody Allen was recently convinced to record audiobooks for his four collections of humorous essays. Between this, Andrew Wylie’s foray into e-books, and the recent news from Amazon, I was worried that old-fashioned cranks like me, who believe in reading books on paper, were finally extinct. I mean, if Woody Allen is on board? But thankfully, Allen brought the crank:

I was persuaded in a moment of apathy when I was convinced I had a fatal illness and would not live much longer. . . . Many people thought it would be a nice idea for me to read my stories, and I gave in. I imagined it would be quite easy for me, and, in fact, it turned out to be monstrously hard. I hated every second of it, regretted that I had agreed to it, and after reading one or two stories each day, found myself exhausted. The discovery I made was that any number of stories are really meant to work, and only work, in the mind’s ear and hearing them out loud diminishes their effectiveness. Some of course hold up amusingly, but it’s no fun hearing a story that’s really meant to be read, which brings me to your next question, and that is that there is no substitute for reading, and there never will be. Hearing something aloud is its own experience, but it’s hard to beat sitting in bed or in a comfortable chair turning the pages of a book, putting it down, and eagerly awaiting the chance to get back to it.

Whew.

Wednesday, July 21st, 2010

In the Ether

In what he is calling “The Summer of (Free) E-book Love,” Jim Hanas is trying to give away as many copies of his first e-book as possible before Labor Day. The e-book contains two of his excellent short stories, “Miss Tennessee” and “The Cryerer.” He’s even set up a phone help line for those who need help downloading it. . . . This excerpt from Tim Parks’ new memoir has me wanting to read the whole thing badly. . . . Greg Baxter writes about 10 autobiographies that helped him write his own book. (On Nietzsche: “Who but a lunatic allows himself to say: ‘I am not a man. I am dynamite’?”) . . . Speaking of Baxter’s book, John Self offers it a great deal of thoughtful praise, and he’s giving away five copies on his blog (you can sign up for the drawing until Saturday night). . . . An interview with Tom Lutz, editor of the Los Angeles Review of Books, which will launch online in the fall. . . . Having read more than 2,500 pages of Dorothy Dunnett’s work since May, Levi Stahl tries to figure out what exactly it is about her books that keeps him coming back for more. . . . Macy Halford pines for the days when she did her research with books, not on the web. . . . A roundup of some developments in the “increasing amount of crossover between the book and fashion worlds these days.”

In what he is calling “The Summer of (Free) E-book Love,” Jim Hanas is trying to give away as many copies of his first e-book as possible before Labor Day. The e-book contains two of his excellent short stories, “Miss Tennessee” and “The Cryerer.” He’s even set up a phone help line for those who need help downloading it. . . . This excerpt from Tim Parks’ new memoir has me wanting to read the whole thing badly. . . . Greg Baxter writes about 10 autobiographies that helped him write his own book. (On Nietzsche: “Who but a lunatic allows himself to say: ‘I am not a man. I am dynamite’?”) . . . Speaking of Baxter’s book, John Self offers it a great deal of thoughtful praise, and he’s giving away five copies on his blog (you can sign up for the drawing until Saturday night). . . . An interview with Tom Lutz, editor of the Los Angeles Review of Books, which will launch online in the fall. . . . Having read more than 2,500 pages of Dorothy Dunnett’s work since May, Levi Stahl tries to figure out what exactly it is about her books that keeps him coming back for more. . . . Macy Halford pines for the days when she did her research with books, not on the web. . . . A roundup of some developments in the “increasing amount of crossover between the book and fashion worlds these days.”

Tuesday, July 20th, 2010

The Laff Box

In his book And Here’s the Kicker

In his book And Here’s the Kicker, Mike Sacks interviewed 21 humor writers about their craft. (Sacks writes funny things himself.) As part of his research, Sacks interviewed Ben Glenn II, an expert in the history of canned laughter, and the result is now up at the Paris Review blog. A piece:

Who invented the canned-laughter machine?

Actually, its official name is the Laff Box, and it was invented by a man named Charles Rolland Douglass. He served in World War II, and when he returned to civilian life, he worked as a broadcast engineer at CBS. Douglass was responsible for everything from recording sound levels during production to adjusting them in post-production. [. . .]

Where did the laughs on the Laff Box originate?

Reportedly, the earliest reactions came from a Marcel Marceau performance in Los Angeles in 1955 or 1956, during his world premiere North American tour. This would make sense, because Marceau was, of course, a mime, and therefore, the only sound in the theater was the audience’s reaction.

Monday, July 19th, 2010

The Beat

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Robert Faggen says that a new collection of correspondence between Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg is not to be missed: “The depth of their development as friends but especially as writers has never been shown more clearly than in this stunning new collection. The letters are sometimes long but almost infallibly interesting.” . . . Dennis Lehane says that Nic Pizzolatto’s new novel, Galveston, ranks with the best of the noir genre, partly because “[it] empathizes with its characters to a degree I’m hard pressed to recall in another recent novel.” . . . Laura Miller reviews Geoffrey O’Brien’s latest, a true-crime story about an esteemed New York family undone by an 1873 murder. Miller calls it “part Victorian family saga, part creepy gothic, full of haunted people drifting through rooms filled with dark, oversize furniture as immobile and dominating as the past they can neither revive nor escape.” . . . Wendy Smith says that in her new novel, Allegra Goodman “has rediscovered her sense of humor.” The book is set during the dotcom bubble, and in it, Goodman “works on a larger social canvas than ever before, armed with an awareness that to comprehend all the scheming and the sorrow, wit is indispensable.” . . . Jackie Wullschlager on four books about photographers and the role they play in defining the art form’s history. . . . James Meek writes about the relationship between Leo and Sofia Tolstoy.

Robert Faggen says that a new collection of correspondence between Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg is not to be missed: “The depth of their development as friends but especially as writers has never been shown more clearly than in this stunning new collection. The letters are sometimes long but almost infallibly interesting.” . . . Dennis Lehane says that Nic Pizzolatto’s new novel, Galveston, ranks with the best of the noir genre, partly because “[it] empathizes with its characters to a degree I’m hard pressed to recall in another recent novel.” . . . Laura Miller reviews Geoffrey O’Brien’s latest, a true-crime story about an esteemed New York family undone by an 1873 murder. Miller calls it “part Victorian family saga, part creepy gothic, full of haunted people drifting through rooms filled with dark, oversize furniture as immobile and dominating as the past they can neither revive nor escape.” . . . Wendy Smith says that in her new novel, Allegra Goodman “has rediscovered her sense of humor.” The book is set during the dotcom bubble, and in it, Goodman “works on a larger social canvas than ever before, armed with an awareness that to comprehend all the scheming and the sorrow, wit is indispensable.” . . . Jackie Wullschlager on four books about photographers and the role they play in defining the art form’s history. . . . James Meek writes about the relationship between Leo and Sofia Tolstoy.

Monday, July 19th, 2010

Shteyngart in the Times, Times Two

Yevgeniya Traps’ review of Gary Shteyngart’s third novel, Super Sad True Love Story, just went up in the Circulating section. Shteyngart made two prominent appearances in Sunday’s New York Times. He lightened up Deborah Solomon in a very funny interview. A piece:

Yevgeniya Traps’ review of Gary Shteyngart’s third novel, Super Sad True Love Story, just went up in the Circulating section. Shteyngart made two prominent appearances in Sunday’s New York Times. He lightened up Deborah Solomon in a very funny interview. A piece:

Were you influenced at all by Fahrenheit 451, which similarly presents a book-free future?

Yes, of course. In fact, that’s what I think Bradbury was concerned about, a future without books, not just an authoritarian government that burns books but a world where people don’t actually want to read.

The death of reading is a longstanding fear of futurists.

Maybe we’re all wrong and there’s going to be a huge comeback in 10 years where all the kids are going to drop their iKindles and start reading like crazy. “Dude, did you read the latest Turgenev? It’s so sick. This dude is like all over the subject of love and serfdom.”

That would be nice.

I don’t know how to read anymore. I can only read 20 or 30 words at a time before taking out my iPhone and caressing it and snuggling with it.

And in a more serious piece, he wrote about the same familiar topic — the fidgety nature of social media and its effects on reading habits — with verve. He starts funny:

With each passing year, scientists estimate that I lose between 6 and 8 percent of my humanity, so that by the close of this decade you will be able to quantify my personality. By the first quarter of 2020 you will be able to understand who I am through a set of metrics as simple as those used to measure the torque of the latest-model Audi or the spring of some brave new toaster.

But he settles down, with emotion, to the topic at hand, the recaptured life of a reader:

I am sitting underneath a tree beside a sturdy summer cottage rebuilt by an ingenious Swedish woman. The birds are twittering, but in a slightly different way than my New York friends. I open a novel, A Short History of Women, by Kate Walbert, a book I will grow to love over the coming week, but at first my data-addled brain is puzzled by the density and length of it (256 pages? how many screens will that fill?), the onrush of feeling and fact, the surprise that someone has let me not into her Facebook account but into the way other minds work. I read and reread the first two pages understanding nothing. Big things are happening. World War I. The suffragist movement. Out of instinct I almost try to press the text of the deckle-edged pages, hoping something will pop up, a link to something trivial and fast. But nothing does. Slowly, and surely, just as the sun begins to swoon over the Hudson River and another Amtrak honks its way past Rhinebeck, delivering its digital refugees upstream, I begin to sense the world between the covers, much as I sense the world around me, a world corporeal and complete, a world that doesn’t need the press of my thumb, because here beneath the weeping willow tree my input is meaningless.

Friday, July 16th, 2010

FSG’s New Look Behind the Curtain

FSG has launched Work in Progress, a monthly feature (”an exhibition, a meet-and-greet, a freak show”) that takes a look behind the scenes at the venerable publisher. The first edition features items from FSG’s extensive Susan Sontag archive. (A 1963 list of potential blurbers for Sontag’s debut novel, The Benefactor, included Auden, Capote, Nabokov, and Paley. Aim high, I say.)

FSG has launched Work in Progress, a monthly feature (”an exhibition, a meet-and-greet, a freak show”) that takes a look behind the scenes at the venerable publisher. The first edition features items from FSG’s extensive Susan Sontag archive. (A 1963 list of potential blurbers for Sontag’s debut novel, The Benefactor, included Auden, Capote, Nabokov, and Paley. Aim high, I say.)

There’s also an interview with three book jacket designers, and an exchange between editor Jonathan Galassi and novelist Jeffrey Eugenides about Eugenides’ in-the-works follow-up to Middlesex. Near the end of the interview, Galassi asks if writing is fun for Eugenides. The reply, in part:

Chekhov said he wrote as easily as a bird sings. That would be nice. I’m like a bird who’s listened to all the other birds singing. Over there, in the next yard (very distant), are the songs I like. For a while I imitated them as best I could, until I figured out my own song, which I am now contentedly singing. Of course, what the bird doesn’t know (because it has a birdbrain) is that it isn’t just a matter of learning one song. You have to come up with a new song for every book. For now, I’ve got the song for this book. And that’s when it becomes fun.

Friday, July 16th, 2010

The Monkey Can’t Play

I recently finished Anthony Holden’s Bigger Deal

I recently finished Anthony Holden’s Bigger Deal, a sequel to Big Deal

, the memoir that made his name as a poker writer. Near the end of the book, he’s at the 2006 World Series of Poker, and I thought he captured the height of poker-boom silliness when he described a press conference during which Pamela Anderson introduced her own online poker site and was grilled about it by Robin Leach, who was “writing a Vegas blog for AOL.” But then two pages later, it was topped by this:

A monkey, name of “Mikey,” has been entered for this year’s main event. It’s a publicity stunt by a Web site called PokerShare, based on the tricksily punning slogan that “any chump” can win the thing. Harrah’s insists that the chimp cannot play as it would be “unhygienic”; the Web site responds that the animal will be wearing a diaper. Eventually, after a long search through its extensive rule book (full of regulations about rabbit-hunting, etc.), Harrah’s sees off PokerShare’s determined representatives with the definitive ruling that the chimp cannot play because it is . . . under twenty-one.

Tuesday, July 13th, 2010

Dissed by Doctorow, Belittled by Bloom

Anis Shivani recently interviewed Adam Langer for the Huffington Post. (A review of Langer’s new novel, The Thieves of Manhattan, is up in the Circulating section.) Many of Shivani’s questions take the form of interpretations of the novel that Langer doesn’t agree with. But these two consecutive questions elicit entertaining answers:

Anis Shivani recently interviewed Adam Langer for the Huffington Post. (A review of Langer’s new novel, The Thieves of Manhattan, is up in the Circulating section.) Many of Shivani’s questions take the form of interpretations of the novel that Langer doesn’t agree with. But these two consecutive questions elicit entertaining answers:

Shivani: Do you have any particularly traumatic experiences with the publishing industry that you’d like to share?

Langer: Oh yes, over the course of my career as journalist and novelist, I’ve been blown off by E. L. Doctorow, condescended to by Harold Bloom, and been subjected to hissy fits by literary agents who, thankfully, never represented me. Along the way, I’ve been treated to lousy herring by Gary Shteyngart, regaled with unprintable, really yucky stories by Jonathan Safran Foer, upbraided for a really dumb reason by Jeffrey Eugenides, and had my debut novel rejected as “unsaleable” by an agent about a year after it had already been sold. Which should have made me feel smug, but that still sort of pisses me off.

Shivani: Did you meet with early success, in terms of getting your first novel accepted for publication, or was it a long, hard road for you?

Langer: If I pretended that my first published novel, Crossing California, was actually the first novel I wrote, I’d say that it was easy. I’d say, yup, I finished the book, got an agent, got a contract, and started work on Book #2. But in saying that, I’d be ignoring the fact that my first novel, Making Tracks, a teen detective story written when I was in high school, is still in a drawer. And so is my second novel, It Takes All Kinds, a 300-page long screed about my first week at Vassar. Also, my third novel, A Rogue in the Limelight, a picaresque journey modeled on Huck Finn and The Confederacy of Dunces, never found the right agent, even though some people (well, my mother) have called it my best novel. One of my earliest agents said that my fourth novel, Indie Jones, a slacker comedy set in Chicago’s independent film world, would easily find a home at Doubleday, but that didn’t happen. And I stopped looking for an agent for my fifth novel, an existential thriller called American Soil, when I realized there was too much personal shit in it and I really didn’t want to deal with having it published. But yeah, once I finished Book #6, it was smooth sailing.

Monday, July 12th, 2010

The Beat

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Laura Miller praises Faithful Place, the new novel by Tana French: “Detective fiction’s legions of brooding sleuths have paid lip service to Nietzsche’s observation that if you look long enough into the abyss, the abyss starts looking back. In French’s novels, the person looking becomes the abyss.” Miller says the settings of French’s novels “[make] Philip Marlowe’s L.A. look like a church picnic.” . . . The Economist reviews a new history of catching waves. (“Surfing is more akin to fly-fishing or bird-watching than to parachute jumping or alligator wrestling.”) . . . Meghan O’Rourke reviews Anne Carson’s highly designed, multimedia tribute to her dead brother. “Despite the inclusion of personal details, Nox (Latin for “night”) is as much an attempt to make sense of the human impulse to mourn as it is a story about a lost sibling.” . . . In yesterday’s New York Times Book Review, Lauren Winner reviewed Eric Lax’s new memoir, “a steady, quiet love letter to a faith he has lost,” and Christopher Hitchens considered Philip Pullman’s reimagined life of Jesus: “It is not merely a reweaving of the synoptic Gospels with the supernatural dimension left out. It is an attempt by an experienced storyteller to show how even the best-plotted stories can get too far out of hand.” . . . Herbert Gold reviews California scholar Kevin Starr’s latest, “an ecstatic meditation on the complicated drama of the Golden Gate Bridge and a chronicle of its history.”

Laura Miller praises Faithful Place, the new novel by Tana French: “Detective fiction’s legions of brooding sleuths have paid lip service to Nietzsche’s observation that if you look long enough into the abyss, the abyss starts looking back. In French’s novels, the person looking becomes the abyss.” Miller says the settings of French’s novels “[make] Philip Marlowe’s L.A. look like a church picnic.” . . . The Economist reviews a new history of catching waves. (“Surfing is more akin to fly-fishing or bird-watching than to parachute jumping or alligator wrestling.”) . . . Meghan O’Rourke reviews Anne Carson’s highly designed, multimedia tribute to her dead brother. “Despite the inclusion of personal details, Nox (Latin for “night”) is as much an attempt to make sense of the human impulse to mourn as it is a story about a lost sibling.” . . . In yesterday’s New York Times Book Review, Lauren Winner reviewed Eric Lax’s new memoir, “a steady, quiet love letter to a faith he has lost,” and Christopher Hitchens considered Philip Pullman’s reimagined life of Jesus: “It is not merely a reweaving of the synoptic Gospels with the supernatural dimension left out. It is an attempt by an experienced storyteller to show how even the best-plotted stories can get too far out of hand.” . . . Herbert Gold reviews California scholar Kevin Starr’s latest, “an ecstatic meditation on the complicated drama of the Golden Gate Bridge and a chronicle of its history.”

Friday, July 9th, 2010

Fall Preview: Nonfiction, Part Two

Drawing Power

Drawing Power by Rick Marschall and Warren Bernard (November 24)

In what promises to be one of the season’s more aesthetically pleasing books, Drawing Power collects mass market print advertisements from the 1890s to the recent past, including ads starring Mickey Mouse and Little Orphan Annie and ads drawn by Dr. Seuss and Rube Goldberg.

There’s a Road to Everywhere Except Where You Came From by Bryan Charles (October 5)

A memoir by the author of Grab On to Me Tightly as if I Knew the Way, and a friend of The Second Pass, about coming to New York City from the Midwest, living in a rapidly changing Brooklyn, developing as a writer, and finding a fateful day job in the World Trade Center.

Bob Dylan In America by Sean Wilentz (September 7)

A notable historian considers the musical icon’s influences, craft, and impact in “a unique blend of fact, interpretation, and affinity.”

On Balance by Adam Phillips (August 31)

A new collection of essays about human psychology (these focusing on “the paradoxes inherent in our appetites and fears”) by the writer and analyst who John Banville called, “One of the finest prose stylists at work in the language, an Emerson of our time.”

Cultures of War by John Dower (September 7)

Historian Dower follows up Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, which won both the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize, with a look at the culture of war reflected in four events: Pearl Harbor, Hiroshima, 9/11, and the invasion of Iraq.

Travels in Siberia by Ian Frazier (October 12)

Two excerpts from Frazier’s travelogue appeared in The New Yorker a few months ago. From the publisher: “The book brims with Mongols, half-crazed Orthodox archpriests, fur seekers, ambassadors of the czar bound for Peking, tea caravans, German scientists, American prospectors, intrepid English nurses, and prisoners and exiles of every kind.”

Mourning Diary by Roland Barthes (October 12)

Beginning the night after his mother died, Barthes wrote a series of 330 brief note cards detailing his own grief and the idea of grief more generally. This volume collects them.

The Emperor of All Maladies by Siddhartha Mukherjee (November 16)

A renowned oncologist’s sprawling history of cancer, from its centuries-long history to the current-day search for a cure. My guess is that this is in the vein of Andrew Solomon’s book about depression, The Noonday Demon.

Titanic Thompson: The Man Who Bet on Everything by Kevin Cook (November 22)

A biography of the road gambler who was Damon Runyon’s model for Sky Masterson in Guys and Dolls. A terrific golfer, Thompson was also a five-time murderer, five-time groom, and someone who ran across Houdini, Al Capone, and Minnesota Fats, among others.

Between Religion and Rationality by Joseph Frank (July 26)

A collection of essays by the esteemed Dostoevsky biographer. Here, he writes more about Dostoevsky, and about the tension in Russian literature (and wider culture) between reason and faith. The publisher claims the book “[offers] insights for general readers and experts alike,” though it arrives with the expert cover price of $60.

How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming by Mike Brown (December 7)

The astronomer who discovered the celestial body that knocked Pluto off the planet list tells his story.

Running the Books by Avi Steinberg (October 19)

A memoir about Steinberg’s time running a library in a tough Boston prison.

A Week at the Airport by Alain de Botton (September 21)

De Botton spent a week at Heathrow Airport as writer-in-residence. This illustrated book recounts his experience of “a place that most of us never slow down enough to see clearly.”

Exiles in Eden by Paul Reyes (August 31)

Journalist Reyes details the foreclosure crisis from a personal perspective, working with his father’s company, which empties out foreclosed homes in Florida.

How to Become a Scandal by Laura Kipnis (August 31)

In her heavily blurbed new book (15 of them on Amazon at the moment), Kipnis (Against Love) writes about four particular scandals to examine why Americans love to watch — and act out — psychodramas.

A Life Like Other People’s by Alan Bennett (September 14)

The prize-winning playwright’s latest work of memoir details his parents’ marriage and the lives of two of his aunts.

Thursday, July 8th, 2010

Fall Preview: Nonfiction, Part One

This is the first of a two-part preview of some notable nonfiction titles being published this fall. Part two will appear tomorrow.

Kingdom Under Glass

Kingdom Under Glass by Jay Kirk (October 26)

Journalist Kirk’s first book is a biography of Carl Akeley, the famed American taxidermist whose early-20th-century African safaris (with Theodore Roosevelt, among others) are the stuff of legend. Publishers Weekly called the book “a beguiling, novelistic portrait of a man and an era straining to hear the call of the wild.”

Love’s Work by Gillian Rose (October 12)

NYRB Classics reissues Rose’s philosophical memoir, written while she was dying of cancer. Arthur Danto said the book “[m]akes whatever else has been written on the deepest issues of human life by the philosophers of our time seem intolerably abstract and even frivolous.”

They Live by Jonathan Lethem (November 1)

Death Wish by Chris Sorrentino (November 1)

These are the first two entries in Soft Skull Press’ new Deep Focus series, which features short books written by notable authors about “the most vital and popular corners of cinema history: midnight movies, the New Hollywood of the sixties and seventies, film noir, screwball comedies, international cult classics, and more.”

Nothing Left to Burn by Jay Varner (September 21)

Varner’s memoir looks back at his childhood in small-town Pennsylvania, with a fire-chief father and arsonist grandfather, and at the present day, when Varner is reporting on fires and accidents for his hometown paper.

FreeDarko presents The Undisputed Guide to Pro Basketball History (November 9)

In time for the new NBA season, the eggheads at the eggheadiest basketball blog around release their second, no doubt beautifully designed, book of hoops analysis.

The Killer of Little Shepherds by Douglas Starr (October 5)

A true-crime account of Joseph Vacher, a serial killer in late 19th-century France, and the groundbreaking forensic science used to catch him.

The Moral Landscape by Sam Harris (October 5)

In his latest polemic, Harris argues that science, without the aid of religion, can tell us all we need to know about morals.

Apathy for the Devil by Nick Kent (August 31)

A British rock journalist recounts his experience of the 1970s, carousing with the Rolling Stones, David Bowie, and the Sex Pistols, among others, and getting hooked on heroin. Published earlier this year in the UK, one review from overseas sums up the conflicted critical reaction: “Kent’s initial attempts to reach back across the opiated canyons of his memory and re-establish contact with the precocious innocence of his formative years feel so clumsily generic that they might as well be ghost- written. . . . [But the book] ends up as a surprisingly clear-eyed and courageous dismantling of the very Dionysian rock mythology which was at once Kent’s meal-ticket and his downfall.”

Life by Keith Richards (October 26)

Speaking of drug-hazy memories, Richards’ autobiography covers everything from his earliest days listening to music to his founding of the Rolling Stones with Mick Jagger to the countless adventures that followed.

My Year of Flops by Nathan Rabin (October 19)

Based on his column for The Onion (where he’s a staffer), Rabin takes a closer look at some of the most notoriously bad performers in cinematic history, including The Last Action Hero and Waterworld.

Wednesday, July 7th, 2010

Skull-Crushing Boredom in the Jungle

At Powell’s, Tom Bissell has a smart piece about the influence of video games on children, and on him as a child:

At Powell’s, Tom Bissell has a smart piece about the influence of video games on children, and on him as a child:

I played a ton of games when I was a kid, certainly, but those games were of an entirely more limited magnitude of invention. Despite the enthusiasm of a youthful Jack Black, one can only run Pitfall Harry through the jungle so many times before skull-crushing boredom sets in. I often wonder how I would have turned out if the video games I play today were around when I was, say, seven. Would I have turned into the reader I am? I’d like to say yes, but I’m not sure I can. Given the contours of my obsessive personality, it’s just as likely that I would have wound up like one of the characters in Infinite Jest or some South Korean Starcraft player, expiring from dehydration after a 50-hour bivouac on the couch.

Wednesday, July 7th, 2010

An Inner Richness

Mark Athitakis links to an interview with Richard Russo in the small-town Wilton Bulletin of Connecticut:

To Mr. Russo, Facebook resembles an attempt to create the sense of community found in small towns. “What is Facebook but an attempt to replicate something lost, a real community? People in small towns can’t avoid each other,” he said. “They have to take each other into account, which may be both the best and worst thing about them.”

What about writers like Sinclair Lewis who have disparaged small towns? “Sinclair Lewis saw such places as breeding grounds for parochial stupidity,” Mr. Russo said. “He’d probably feel the same about Facebook, where like-minded morons gather and draw solace from the fact that there are so many others out there with identical misconceptions. Sherwood Anderson, with whom I feel a closer kinship, saw in isolated small town lives an inner richness.”

Wednesday, July 7th, 2010

Culture Diary, Part One

The Paris Review blog very kindly asked me to participate in its Culture Diaries series, in which one person a week details their reading, watching, and listening for seven days. The first installment of mine just went up. It includes David Shields, Richard Russo, William James, Joan Rivers, and Curious George.

Tuesday, July 6th, 2010

Fall Preview: Supplement

The Millions does us all a favor by rounding up some of the most anticipated books scheduled for late summer and fall. As always, the season is crowded with big names: Franzen, Roth, Ozick, Cunningham, Krauss, Rushdie. Heck, Mark Twain has a new book coming out. The Millions covers all of these and more. And yet there’s always room for more in the fall — so here are 13 additional novels that I’m keeping an eye on in the coming months. (Release dates are the most recently posted on Amazon.) A nonfiction preview of the fall may follow at some point in the near future.

How to Read the Air

How to Read the Air by Dinaw Mengestu (October 14)

Mengestu’s first novel, The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears, was one of the best debuts of recent years. This sophomore effort concerns Ethiopian immigrants to the U.S. and their son, who recreates a road trip his parents took before he was born.

To the End of the Land by David Grossman (September 21)

Grossman’s highly anticipated novel is based, in part, on his own experience of losing a 20-year-old son to battle in Lebanon. In the novel, an Israeli mother wanders away from home with a former lover in order to avoid hearing news of her soldier son’s fate.

How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe by Charles Yu (September 7)

The theme of parents and children continues. Sarah Weinman has already raved about Yu’s first novel, saying: “Yu’s literary pyrotechnics come in a marvelously entertaining and accessible package, featuring a reluctant, time machine-operating hero on a continual quest to discover what really happened to his missing father, a mysterious book possibly answering all, and a computer with the most idiosyncratic personality since HAL or Deep Thought.”

The Art of Losing by Rebecca Connell (September 28)

In Connell’s debut, part thriller and part romance, a 23-year-old woman secretly involves herself in the life of a man she holds responsible for her mother’s death.

The Wrong Blood by Manuel de Lope (September 28)

De Lope is the author of more than a dozen books, and this is the first translated to English. Moving back and forth through time, it tells the story of two women whose lives are upended by the Spanish Civil War.

The Instructions by Adam Levin (November 1)

Levin’s debut novel runs to more than 900 pages, and chronicles four days in the life of Gurion Maccabee, a 10-year-old with a messiah complex. The publisher (McSweeney’s) says the novel combines “the crackling voice of Philip Roth with the encyclopedic mind of David Foster Wallace.” So, no pressure or anything.

Skippy Dies by Paul Murray (August 31)

Published as a box set of three books in the UK, Murray’s latest comes to the U.S. as one big volume (nearly 700 pages). Speaking of high expectations, the promotional copy compares the fictional boarding school at the center of this adolescent murder mystery to Harry Potter’s Hogwarts School and Enfield Tennis Academy in Infinite Jest.

You Were Wrong by Matthew Sharpe (August 31)

Sharpe’s last novel was the underrated satirical joyride Jamestown. This new, slender novel is about Karl Floor, a friendless man who is drawn into the mysterious social world of a woman he finds robbing his house.

Our Tragic Universe by Scarlett Thomas (September 1)

In Thomas’ second novel, Meg Carpenter, broke and nearing the end of her rope, agrees to review a pseudo-scientific book that sends her reeling into the world of the supernatural.

The World as I Found It by Bruce Duffy (September 21)

The New York Review of Books reissues Duffy’s debut novel from 1987, a sprawling fictionalized account of the life of philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. In 1997, A. O. Scott called the book “one of the more astonishing literary debuts in recent memory.”

The Report by Jessica Francis Kane (August 31)

Kane’s first novel (after a collection of short stories) focuses on a night in 1943 when 173 Londoners died on the steps of a train station, attempting to seek shelter during an air raid. Laurence Dunne is the magistrate charged with investigating the incident and writing a report about it, and the novel chronicles his experience then and several decades later.

Exley by Brock Clarke (October 5)

Clarke’s follow-up to the hit An Arsonist’s Guide to Writers’ Homes in New England stars Miller, a nine-year-old boy who wants to find his father, who has disappeared. He plans to enlist his father’s favorite author in the effort, which is complicated by the fact that the author — Frederick Exley — is dead.

The Life and Opinions of Maf the Dog, and of His Friend Marilyn Monroe by Andrew O’Hagan (December 6)

O’Hagan’s latest is what the title promises, which might seem like an impossibly precious gimmick. But reviews from the UK, where the book was published earlier this year, were generally positive, praising the book as an inventive look at Monroe and her era.