Archives, March, 2009

Monday, March 30th, 2009

Henry Sene Yee discusses the considerations that went into producing the cover for Dave Cullen’s Columbine, which is likely to be on many lists of the year’s best covers. The post includes some early drafts that didn’t make it because they were “too pretty” for the subject, but they’re still worth seeing.

(Via The Book Design Review)

Monday, March 30th, 2009

A brief update about The Second Pass’ tentacles: You can join the site’s Facebook group here. Also, at the bottom of the screen, in the small print, there’s a link to the site’s RSS feed. As someone who runs a web site, I should know more about RSS feeds than I do. If you have trouble with it, drop me a line and I’ll get in touch with my far more knowledgeable troubleshooters.

Lastly, if you’ve been enjoying your time around here, please sign up for the newsletter if you haven’t already, by entering your e-mail address in the space provided under the Backlist section. Thanks.

Monday, March 30th, 2009

This is the first in a regular series that will highlight books recently acquired for future publication. Each post will feature a book we’re looking forward to, and a book we’re . . . not.

The Cherry:

The final volume in historian Rick Perlstein’s “Backlash” trilogy, covering the 1970s and the rise of Ronald Reagan (following Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America , and Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus

, and Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus ).

).

The Pit:

Tim LaHaye and Craig Parshall’s Endgame, in which the use of a sophisticated military defense technology capable of returning nuclear missiles to their place of origin causes a series of events to unfold which eventually leads to the prophesied Rapture of the Church and the Last Days of mankind.

Friday, March 27th, 2009

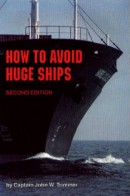

This year’s Bookseller/Diagram Prize, for the year’s oddest book title, has been awarded to:

This year’s Bookseller/Diagram Prize, for the year’s oddest book title, has been awarded to:

The 2009-2014 World Outlook for 60-milligram Containers of Fromage Frais

The prize was founded in 1978, and it’s voted on by the public in the UK. Personally, I would have cast my vote this year for the runner-up, Baboon Metaphysics. Another of this year’s finalists — Curbside Consultation of the Colon — suggests that we may have reached the stage where authors are keeping the prize in mind when naming their work.

Past winners include Weeds In a Changing World, How to Avoid Huge Ships, and perhaps the all-time champ, Bombproof Your Horse.

Thursday, March 26th, 2009

This post is written by a guest, Levi Stahl, who blogs at I’ve Been Reading Lately:

This post is written by a guest, Levi Stahl, who blogs at I’ve Been Reading Lately:

The many, many readers who hate Moby-Dick commonly cite its pages and pages about whales as evidence of its failure as a novel. What on earth is all that relatively undigested encyclopedia-style information doing in the middle of a book that, at least in its early chapters, promises to tell us a story?

Those of us who’ve fallen under Melville’s spell, while we understand that complaint, would argue that it misses the point: the information about whales is there because Ishmael (and Melville) wants to wrestle this unruly world to the ground, encompass and understand it — but all while acknowledging its disorganized glory. Ishmael can’t ever quite codify his knowledge of whales, and in fact, like many other initiatives in the novel, his attempt breaks off abruptly, overtaken like so much else in life by other, more urgent demands. But those of us who find ourselves reading Moby-Dick over and over again understand the impulse that drives him — and thus, in a way, the impulse that drives Ahab.

Dan Beachy-Quick, in his introduction to his A Whaler’s Dictionary , explains that the book “does not finish Ishmael’s failed cetological endeavor — it simply repeats the failure in a different guise.” From there, Beachy-Quick follows his thoughts through a literary and philosophical lexicon that runs from “Accuracy” to “You/Thou,” with cross-references leading us ever deeper into its byways. Under “Fear,” he investigates Starbuck’s rule that no man may serve in his boat “who is not afraid of a whale.” The entry for “Mincer,” the word for the man whose job is to cut blubber, leads unexpectedly to a parable about writing.

, explains that the book “does not finish Ishmael’s failed cetological endeavor — it simply repeats the failure in a different guise.” From there, Beachy-Quick follows his thoughts through a literary and philosophical lexicon that runs from “Accuracy” to “You/Thou,” with cross-references leading us ever deeper into its byways. Under “Fear,” he investigates Starbuck’s rule that no man may serve in his boat “who is not afraid of a whale.” The entry for “Mincer,” the word for the man whose job is to cut blubber, leads unexpectedly to a parable about writing.

A Whaler’s Dictionary is, as Beachy-Quick himself advises, not a book to be read straight through. It’s a book to be kept at the bedside, flipped through when the pretense of order has taken too firm a grasp of one’s life. As the entry for “Line” notes, “The line connects one to what one wants. The whaler wants the whale. . . . By the line we know when we’re attached to what we desire, and by the line we know when what we desire has escaped.”

Like Moby-Dick, this book is ever-elusive; like Moby-Dick, it rewards our continued pursuit.

Thursday, March 26th, 2009

Wednesday, March 25th, 2009

Just a friendly reminder that The Shelf is a feature open to any and all of you who read The Second Pass. I’d love to hear about what you’re enjoying these days, whether it’s just been published or it had been gathering dust in an attic for decades. Send 75-125 words about any pick to john@thesecondpass.com.

Wednesday, March 25th, 2009

From The Journals of John Cheever :

:

Easter Eve: dyeing eggs and stuffing the turkey, all pleasant. Easter morning sunny and cool. To church with Susie and Ben. The church for once is full. I am delighted to hear that Christ is risen. I think that it is not against God’s will to have my generative powers refreshed by the face of a pretty woman in a forward pew or to wonder about the hairy and somehow limpid young man on my left. It is the combination of hairiness and wistful grace that seems to mark him. When I hear that Mary found at the tomb a man in white raiment I am incredulous. It is hard for me to believe that God expressed His will, His intent in such a specific image. But when I go to the altar I am deeply moved. The chancel is full of lilies and their fragrance seems as fresh as it is heavy; a sign of good cheer. And that this message should have been revealed to us and that we should cherish it seems to be our finest triumph. Here in the chancel we glimpse some vision of transcendent love, some willing triumph over death and all its lewd guises. And if it is no more than willingness, how wonderful that is in itself. Walk with my youngest son in the sun. How my whole love of life seems to gather around his form; how he fills me with the finest ambitions. Birds sing. There is a little shimmer of heat. The moment of darkness is gone. He throws sticks into the water, which is a perfectly clear, shallow, and rippled scarf of light. He shuffles through the old leaves.

Later we go to the B.s’ for the Easter-egg hunt; but I am smitten suddenly with shyness, my smile is strained, my sensibilities are inflamed, I am round-shouldered and bent-necked and dreary and nothing but a pint of bourbon will straighten me out. I count on painkillers until ten, when I retire and, half asleep — courage, lustiness, cleanliness, love, charity, strength, industry, intelligence, vision — I recount to myself a dozen times those virtues I admire.

Tuesday, March 24th, 2009

If science fiction, which has gotten some play around here today, often requires thinking big — about the unknowable future, about human nature, about the broad consequences of catastrophe — then what’s the opposite of that? I submit that it may be writing about flies. Not giant, humanity-enslaving flies that have hatched from someone’s sinister lab (that must be the plot of some book, right?) but just, you know, flies. Here are two passages, from two great books — Hunger by Knut Hamsun and Zeno’s Conscience by Italo Svevo. Both excerpts involve writers who are distracted by the pests and end up closely (and beautifully and humorously) observing them. Hamsun first:

If science fiction, which has gotten some play around here today, often requires thinking big — about the unknowable future, about human nature, about the broad consequences of catastrophe — then what’s the opposite of that? I submit that it may be writing about flies. Not giant, humanity-enslaving flies that have hatched from someone’s sinister lab (that must be the plot of some book, right?) but just, you know, flies. Here are two passages, from two great books — Hunger by Knut Hamsun and Zeno’s Conscience by Italo Svevo. Both excerpts involve writers who are distracted by the pests and end up closely (and beautifully and humorously) observing them. Hamsun first:

However, I was unable to write. After a couple of lines, nothing more wanted to come; my thoughts were elsewhere and I couldn’t pull myself up to the effort. Everything around bothered me and distracted me; everything I saw obsessed me. Some flies and gnats were sitting on my paper and this disturbed me; I breathed on them to make them go, then blew harder and harder, but it did no good. The tiny beasts lowered their behinds, made themselves heavy, and struggled against the wind until their thin legs were bent. They were absolutely not going to leave the place. They would always find something to get hold of, bracing their heels against a comma or an unevenness in the paper, and they intended to stay exactly where they were until they themselves decided it was the right time to go.

And now Svevo:

Late one night I had come home and, rather than go to bed, I had entered my little study and turned on the gas. In the light a fly began to torment me. I managed to give it a tap — a light one, however, to avoid soiling my hand. I forgot about it, but then I saw it in the center of the table as it was coming to. It was motionless, erect, and it seemed taller than before, because one of its little legs was paralyzed and couldn’t bend. With its two hind legs it assiduously smoothed its wings. It tried to move, but turned over on its back. It righted itself and stubbornly resumed its assiduous task.

I then wrote those verses, amazed at having discovered that the little organism, filled with such pain, was inspired in its immense effort by two errors: first of all, by the stubborn smoothing of its wings, which were unharmed, the insect revealed that it didn’t know which organ was the source of its pain, and in the determination of that effort it revealed that its minuscule mind contained a fundamental belief that good health is the birthright of all and must surely return when it abandons us. These were errors that can easily be excused in an insect, which lives only a single season and hasn’t time to accumulate experience.

Tuesday, March 24th, 2009

If Jon Fasman’s review of Riddley Walker (posted in the Backlist section today — follow the fiery photo of nuclear destruction) puts you in a sci-fi mood, I recommend the Guardian’s list of the best books in the genre. (In a note he sent me this morning, Jon wrote, “my point was that even if [Riddley Walker] is science fiction, it still is literature. I’m not arguing for its removal from the former category; I’m arguing that the category boundary is altogether undesirable.”) Hoban’s novel is included on the Guardian’s list, which comes in three parts — first here, then here, and finally here. It’s actually a subset of the paper’s longer list of 1,000 novels. Good for browsing…

Monday, March 23rd, 2009

After 48 games in four days, three straight days without basketball might be a harrowing prospect for some. To pass the time until Thursday night, maybe Seth Davis’ new book, When March Went Mad, will do the trick. In it, Davis chronicles the 1979 college basketball championship between Magic Johnson’s Michigan State and Larry Bird’s Indiana State. The Wall Street Journal offers an assessment here:

After 48 games in four days, three straight days without basketball might be a harrowing prospect for some. To pass the time until Thursday night, maybe Seth Davis’ new book, When March Went Mad, will do the trick. In it, Davis chronicles the 1979 college basketball championship between Magic Johnson’s Michigan State and Larry Bird’s Indiana State. The Wall Street Journal offers an assessment here:

In Mr. Davis’s well-reported account, we see glimpses of the future routing the past. In an NBC network production meeting the Sunday between the semifinals and final, one producer wanted to lead the prime-time championship game broadcast with a feature on ISU’s ailing Bob King, only to be overruled by the executive producer of NBC Sports, Don Ohlmeyer, who saw clearly that the only story that mattered was the study in contrasts of Magic versus Bird — big school versus small school, urban versus rural, ebullient versus taciturn, black versus white — two otherworldly athletes who’d raised their respective schools to the pinnacle of the college game.

Posted by

admin at 11:24 AM

Friday, March 20th, 2009

Last night, I was browsing in a neighborhood bookstore with a friend. I looked at the two or three shelves that the store has reserved for the New York Review of Books imprint (which brings back, in handsome volumes, lost classics and curiosities), and we had the following conversation:

Last night, I was browsing in a neighborhood bookstore with a friend. I looked at the two or three shelves that the store has reserved for the New York Review of Books imprint (which brings back, in handsome volumes, lost classics and curiosities), and we had the following conversation:

Me: I’d like to have a feature on the site where someone reviews all of the books in the NYRB series one at a time, kind of like that one guy does with the Criterion Collection.

Friend: Yeah, that’s not gonna happen.

Me: Why? Because there are too many of them?

Friend: Yes, there are too many.

Me: Well, maybe it could be more than one person reviewing them.

Friend: Now that’s an idea.

An idea for another day, surely. For now, I’m interested in L.J. Davis’ A Meaningful Life, which NYRB published last week with an introduction by Jonathan Lethem. Lethem grew up down the block from Davis in Brooklyn, and was friends with his son, Jeremy. The entire introduction can be read here. A taste:

L.J., by refusing to blur the paradoxes of racial and class misunderstanding in idealist sentiment, was “un-PC” before there was such a thing. By being so, he turned some of his neighbors against him, exemplifying a loneliness he, from evidence of his books, already felt as a innate life condition. That he also chose with his wife to adopt two black daughters to raise in his brownstone alongside their two white sons is a fact that still stirs me in its strangeness and beauty. I remember thinking even as a teenager that L.J. had made his home a kind of allegory of the neighborhood as a whole, perhaps partly in order that he might refuse to stand above or apart from it. Then again, with characteristic dryness (unforgivable in the eyes of some local parents), L.J. once awarded a friend of mine and Jeremy’s the Dickensian nickname “Muggable Tim,” and recommended we avoid walking the streets with him. When after thirty-odd years of personal shame at such stuff I finally managed to open my mouth in The Fortress of Solitude, I had L.J. to thank.

Friday, March 20th, 2009

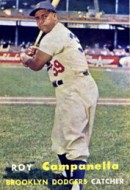

Next week, I’ll be posting a full review of Forever Blue, Michael D’Antonio’s new book about the Brooklyn Dodgers and their widely reviled owner Walter O’Malley. For now, the New York Times baseball blog Bats has a lengthy interview with the author:

Next week, I’ll be posting a full review of Forever Blue, Michael D’Antonio’s new book about the Brooklyn Dodgers and their widely reviled owner Walter O’Malley. For now, the New York Times baseball blog Bats has a lengthy interview with the author:

Q: Forever Blue describes the cultural and demographic shifts in Brooklyn at mid-century. Did Walter O’Malley, by decamping with the Dodgers, crush Brooklyn’s spirit?

A: Some people are still so upset about the departure of the Dodgers, and so unwilling to consider that O’Malley wasn’t solely responsible, that I’m looking for a tomato-proof suit to wear when I talk about the book in front of Brooklyn audiences.

Thursday, March 19th, 2009

Elizabeth Bishop, in a 1963 letter to Robert Lowell, about the movie criticism in Partisan Review, which was written by Pauline Kael:

. . . WHO wrote those idiotic movie reviews? I think she must be somebody’s mistress?

Thursday, March 19th, 2009

Richard Ford says that Frank Bascombe was not intended to be Everyman. . . . Wyatt Mason reacts to the reaction to an alleged portrait of Shakespeare, and the New Republic offers a slide show of images of The Bard. . . . The second round of the Tournament of Books begins with Maud Newton having her say about 2666. And those judging the judges continue their gleeful undermining of the official results: “After 900 pages the revelation at the end is barely worth the calories required to shrug.” . . . I recommend you visit the site Odd Books for gems like this. And this one, which has to be in the running for Best Book Title of All Time.

Thursday, March 19th, 2009

I just discovered a piece by Jim Knipfel that ran in the New Haven Review late last year, called “To Be Perfectly Honest: Why fiction can be more truthful than memoirs.” It’s inspired by the James Frey controversy, about which I’ve heard more than enough, but Knipfel makes it fresh by recounting his own experience writing about (and trying to accurately remember) real life. (I read and enjoyed his memoir Slackjaw a few years back.)

The whole essay is worth a read, but the conclusion is brief: “Point being, in this day and age, all memoirs are novels, thanks to illiterate, paranoid lawyers.”

Wednesday, March 18th, 2009

Having had a fleeting experience with the book’s production, I can highly recommend Mr. America, Mark Adams’ just-released biography of Bernarr Macfadden, an American who lived from 1868 to 1955 and had enough idiosyncrasies to fill an encyclopedia. (Adams’ book is a more manageable 304 pages.)

Having had a fleeting experience with the book’s production, I can highly recommend Mr. America, Mark Adams’ just-released biography of Bernarr Macfadden, an American who lived from 1868 to 1955 and had enough idiosyncrasies to fill an encyclopedia. (Adams’ book is a more manageable 304 pages.)

Macfadden was a fitness nut (emphasis on the nut) who did more than anyone else to shape the exercise- and diet-obsessed branch of our culture. The book’s handsome web site features an interview with Adams, including this:

Q: You tried out some of Macfadden’s regimens on yourself. Did they work?

A: Some of them worked fantastically well. His raw-food diet essentially changed my body’s chemistry. My skin cleared up, my hair became silkier and I even smelled better. You sort of get used to your own scent over the years, so when it changes suddenly it’s a little disconcerting. Even my dog was confused.

The Washington Post has already called the book “hilarious” and “delightful,” but the review wasn’t limited to adjectives. I liked this part:

[Macfadden is] a figure so intensely American that the title of Mark Adams’s hilarious biography seems almost like underkill. If Macfadden hadn’t existed, we would have had to invent him, yes . . . but who could have? A guy who ate sand by the handfuls, plugged his fedora with holes to let his brain breathe and insisted on naming his third daughter “Brawnda” (emphasis on the “brawn”)? A guy who created a “Peniscope” to “reinvigorate the hidden vitality centers of tired executives,” who believed so profoundly in colonic irrigations that he called himself “B.M.,” who filed papers to start his own religion and celebrated his 84th birthday by parachuting into the Seine? Theodore Dreiser throws up his hands. Sinclair Lewis runs screaming from the scene.

Tuesday, March 17th, 2009

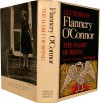

Carlene Bauer writes about Flannery O’Connor’s letters in her review of Flannery (above). One of the moments in the collection that most potently combines O’Connor’s humor and crustiness comes in a letter to her longtime correspondent Betty Hester. In it, the author bristles at a review of her story collection A Good Man is Hard to Find:

The notice in the New Yorker was not only moronic, it was unsigned. It was a case in which it is easy to see that the moral sense has been bred out of certain sections of the population, like the wings have been bred off certain chickens to produce more white meat on them. This is a generation of wingless chickens, which I suppose is what Nietzsche meant when he said God was dead.

I am mighty tired of reading reviews that call A Good Man brutal and sarcastic. The stories are hard but they are hard because there is nothing harder or less sentimental than Christian realism. I believe that there are many rough beasts now slouching toward Bethlehem to be born and that I have reported the progress of a few of them, and when I see these stories described as horror stories I am always amused because the reviewer always has hold of the wrong horror.

Another two sentences, also to Hester, that I wanted to share:

You have to be able to dominate the existence that you characterize. That is why I write about people who are more or less primitive.

Tuesday, March 17th, 2009

In 1964, Katherine Anne Porter wrote a brief appreciation of Flannery O’Connor, who had recently died. The two authors had met, Porter writes, “only three times over a period, I think, of three years or more.” An excerpt from Porter’s essay:

She managed to mix, somehow, two very different kinds of chickens and produced a bird hitherto unseen in this world. I asked her if she were going to send it to the County Fair. “I might, but first I must find a name for it. You name it!” she said. I thought of it many times but no fitting name for that creature ever occurred to me. And no fitting word now occurs to me to describe her stories, her particular style, her view of life, but I know its greatness and I see it — and see that it was one of the great gifts of our times.

Tuesday, March 17th, 2009

I’m a fan of author’s letters, with some of my favorites including those by Raymond Chandler (not always easy to find, but well worth the search), Philip Larkin, William James, and Flannery O’Connor. (A review of Brad Gooch’s new O’Connor biography will go up in Circulating a little later today.) But because so many epistolary collections are out of print — and because few stores have a discrete section for those that are in print — it can be hard to know what’s out there. In a smart review of the first volume of Samuel Beckett’s correspondence, Gabriel Josipovici offers the beginning of a list of must-haves:

I’m a fan of author’s letters, with some of my favorites including those by Raymond Chandler (not always easy to find, but well worth the search), Philip Larkin, William James, and Flannery O’Connor. (A review of Brad Gooch’s new O’Connor biography will go up in Circulating a little later today.) But because so many epistolary collections are out of print — and because few stores have a discrete section for those that are in print — it can be hard to know what’s out there. In a smart review of the first volume of Samuel Beckett’s correspondence, Gabriel Josipovici offers the beginning of a list of must-haves:

The letters of some of the greatest artists of their day, of Wordsworth and Cézanne, Proust and Eliot, for example, though occasionally moving and of interest because of who they were, would never figure in anyone’s list of the ten or twenty greatest books of their time. The letters of Keats and van Gogh, Kafka and Wallace Stevens certainly would. And so, on the evidence of this volume, would those of Samuel Beckett.

Monday, March 16th, 2009

From The Risk Pool by Richard Russo:

Among my entrepreneurial activities that summer, I salvaged golf balls from the narrow pond that served as a hazard on the thirteenth and fourteenth holes of the Mohawk Country Club. To judge from its location, you wouldn’t have thought it would come into play on either hole, since each offered a wide fairway and every opportunity to go around the water, but I doubted it could have attracted more balls had it been twice as large and right in front of the green. The more people faced away from the water, stared off into the friendly fairway, the more surely their ball would be destined for the pond. One afternoon before it had occurred to me that I might retrieve the balls that were down there, I sat on my bike for three hours and charted in my mind where the tee shots dropped, growing more and more amazed at the dense concentration of shots that ended up in the small strip of water. It was enough to make you reconsider the wisdom of deciding, on the outset of any human endeavor, that there was this one thing you didn’t want to do.

Friday, March 13th, 2009

The Chicago-based magazine Stop Smiling, to which I’ve contributed in the past, recently published its annual “20 Interviews” issue, and it’s packed with literary figures, including Paul Auster, Jonathan Lethem, Jane Mayer, Frederick Seidel, and Junot Díaz. In addition to sounding excited about a new novel in progress (great news, considering the famously long gestation of his Pulitzer-winning The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao), Díaz talks about film adaptations (Oscar Wao is big-screen-bound) and hip-hop. A taste of his thoughts on each subject:

SS: And as far as the Oscar movie goes, you’re detached enough that even if they cast Wilmer Valderrama as Oscar, it’s not going to break your heart?

JD: Well, you would want things to work out for the best. Not that I’m bloodless about the thing, but at the same time there’s only so much that you can control. If there’s an adaptation made, I want it to be the best adaptation possible, but I’m not going to fuckin’ throw myself off a bridge if it’s not, because it’s not in my control. You’ve got to be realistic about it. You’re not talking about human beings, you’re talking about corporations. Corporations don’t have feelings, they don’t have sentiments. So you’ve got to be careful about how you apply your own affect toward entities that have no affect. In Santo Domingo they always call it the fight between the rock and the egg. Who’s gonna win?

And:

SS: You came up in the years before rap became a billion-dollar industry. In the Eighties, rap was still a highly marginalized music that catered to a marginalized population of New York youth. Did you identify with it immediately for those reasons?

JD: I think part of what is interesting about this novel is that it just takes the idiom of hip-hop as a given. . . . For me, as someone who grew up in this world just listening to it, we had this understanding that it was just normal. . . . I thought that that was what was really important in Oscar Wao. I wanted to make the hip-hopness of the book normative, and not something that was sensational. Which I think is very important, because one of the things that happens with this economic shift in hip-hop from a local market to an international brand is that they were really trying to push people into becoming this sensational lifestyle, this almost pseudo-religious practice. And when we were coming up in the Eighties, it wasn’t like that, man. You loved hip-hop, that was that. But you didn’t think of hip-hop as this salvation. Now there’s a lot of corporate money in getting young people to embrace hip-hop in ways that would seem very strange to a lot of people from my era. If you took kids from 1986, 1987 and time-traveled them to right now, I think they would find some of the ways that people are like “hip-hop is religion” or “hip-hop explains the universe” really weird. It was meant to be an organic part of people’s lives, it wasn’t meant to replace people’s lives.

Thursday, March 12th, 2009

Frederick the Great, on the philosopher La Mettrie:

He was merry, a good devil, a good doctor, and a very bad author. By not reading his books, one can be very content.

(This anti-blurb was found in Simon Critchley’s The Book of Dead Philosophers, which will receive a full review on this site soon.)

Thursday, March 12th, 2009

Caleb Crain thoughtfully reviews a new book about kindness: “Kindness stumbled in the Christian era, Phillips and Taylor write, when thinkers like Augustine attached to it the idea of self-sacrifice, and it descended from a refined pleasure to a mere duty.” . . . The Believer awards its Fifth Annual Book Award to Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins, “the sort of book that the phrase ‘spoiler alert’ was invented for.” . . . Lorrie Moore reviews a new biography of Donald Barthelme. . . . Joseph Sullivan admires the simple beauty of the design for George Steiner’s two most recent books. . . . Speaking of book covers, this thought had occurred to me, too.

Wednesday, March 11th, 2009

A letter from Henry James to his brother William, dated November 23, 1905:

A letter from Henry James to his brother William, dated November 23, 1905:

Dearest William,

. . . I mean (in response to what you write me of your having read the Golden B[owl]) to try to produce some uncanny form of thing, in fiction, that will gratify you, as Brother — but let me say, dear William, that I shall greatly be humiliated if you do like it, and thereby lump it, in your affection, with things, of the current age, that I have heard you express admiration for and that I would sooner descend to a dishonoured grave than have written. Still I will write you your book, on that two-and-two-make-four system on which all the awful truck that surrounds us is produced, and then descend to my dishonoured grave — taking up the art of the slate pencil instead of, longer, the art of the brush (vide my lecture on Balzac). But it is, seriously, too late at night, and I am too tired, for me to express myself on this question — beyond saying that I’m always sorry when I hear of your reading anything of mine, and always hope you won’t — you seem to me so constitutionally unable to “enjoy” it, and so condemned to look at it from a point of view remotely alien to mine in writing it, and to the conditions out of which, as mine, it has inevitably sprung — so that all the intentions that have been its main reason for being (with me) appear never to have reached you at all — and you appear even to assume that the life, the elements forming its subject-matter, deviate from felicity in not having an impossible analogy with the life in Cambridge. I see nowhere about me done or dreamed of the things that alone for me constitute the interest of the doing of the novel — and yet it is in a sacrifice of them on their very own ground that the thing you suggest to me evidently consists. It shows how far apart and to what different ends we have had to work out (very naturally and properly!) our respective intellectual lives. And yet I can read you with rapture — having three weeks ago spent three or four days with Manton Marble at Brighton and found in his hands ever so many of your recent papers and discourses, which, having margin of mornings in my room, through both breakfasting and lunching there (by the habit of the house,) I found time to read several of — with the effect of asking you, earnestly, to address me some of those that I so often, in Irving St., saw you address to others who were not your brother. I had no time to read them there. Philosophically, in short, I am “with” you, almost completely, and you ought to take account of this and get me over altogether….

But oh, fondly, good-night!

Ever your

Henry

Wednesday, March 11th, 2009

If, like me, you’re itchy for the NCAA tournament to get started, you can scratch at The Morning News, which has kicked off its Fifth Annual Tournament of Books. The competition dispenses with the crowded early rounds and skips straight to the Sweet 16. Two widely acclaimed books – Netherland by Joseph O’Neill and The White Tiger by Aravind Adiga – have already been knocked out.

Balancing those upsets is a predictable win by Roberto Bolaño’s massive 2666. After each round, Kevin Guilfoile and John Warner judge the judging, which is often where the real action happens. Guilfoile swims against the critical tide:

It’s possible that 2666 is a work of art, and it might even be an important one about the persistence of violence and death, cruelty and corruption. What I’m pretty sure it isn’t is a good novel.

He goes on to say that it’s “sexist, homophobic, boring, repetitive, misogynistic, tedious, repetitive, infuriating, monotonous, repetitive, maddening. It also repeats itself.”

I haven’t read 2666, and one of the reasons is that I couldn’t get through Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives, which also received tremendous levels of praise. For the first 75 pages or so, I understood why. Then, the book suddenly turned into an exercise in how many characters he could introduce per page without doing much more, and when that exercise showed no signs of abating, I lost interest. A good friend, and one of the smartest readers I know, said she also struggled with that section, but that a payoff at the end of the novel makes everything worth it.

Tuesday, March 10th, 2009

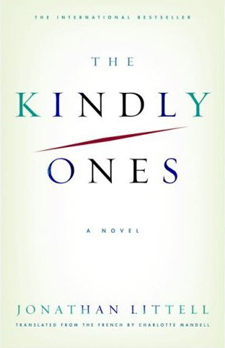

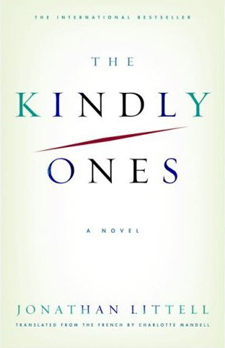

Just a brief round-up for anyone who’s missed the predictably and forcefully split critical reaction to Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones, a nearly 1,000-page novel told from the decidedly unsentimental perspective of Max Aue, an SS officer during the Holocaust. Originally published in French, the book was a commercial and critical success. It’s too soon to judge its commercial success in America (it was published here last week), but it has people talking, which seems to be, for better or worse, its raison d’être.

Just a brief round-up for anyone who’s missed the predictably and forcefully split critical reaction to Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones, a nearly 1,000-page novel told from the decidedly unsentimental perspective of Max Aue, an SS officer during the Holocaust. Originally published in French, the book was a commercial and critical success. It’s too soon to judge its commercial success in America (it was published here last week), but it has people talking, which seems to be, for better or worse, its raison d’être.

Michiko Kakutani, first out of the gate in the New York Times, snidely judged that the book’s champions “seem to have mistaken perversity for daring, pretension for ambition, an odious stunt for contrarian cleverness.”

Soon after, Michael Korda reviewed the book, and addressed its greatness as if answering a rhetorical question: “Yes, it’s a masterpiece,” he wrote, a work of “astonishing brutality, originality, and force.”

Somewhere between this dismissal and rave is Daniel Mendelsohn’s typically astute take in the New York Review of Books. Mendelsohn, renowned for his Classics background, brings a contextual knowledge to the novel that not many of its readers will. He argues that the book succeeds in “weaving together the dreadful and the mundane in an unsettlingly persuasive way.”

It’s that “mundane” that gives me (and Mendelsohn) pause. The Kindly Ones is not the first artistic endeavor to address the way that otherwise normal people can commit terrible acts. But from the reviews (including Korda’s rhapsody), it would seem that Aue is anything but normal, which could undermine the project. As Kakutani wrote:

Although Aue contends that he is “a man like other men,” “a man like you” and depicts himself as a cultivated intellectual who reads Flaubert and Kant, his story is hardly a case study in the banality of evil. Whereas the heroes of the play “Good” and the movie “Mephisto” were ordinary enough men who out of ambition or opportunism or weakness turned to the dark side and embraced the Nazi cause, Aue is clearly a deranged creature . . . Unable to understand Aue, much less sympathize with him, the reader is not goaded, as in the case of “Good” and “Mephisto,” to question his or her own capacity for moral compromise. Instead Mr. Littell simply gives us a monster talking at monstrous length about his monstrous deeds . . .

Or as Mendelsohn writes about Aue’s sadomasochistic, incestuous predilections:

. . . the problem, in the end, is that they make it harder and harder—and, finally, impossible—to see him as anything but, well, “inhuman,” a “monster,” precisely the kind of cliché of depravity that so many of this novel’s strongest passages successfully resist.

Tuesday, March 10th, 2009

In this promotional video, Zoë Heller talks about her new novel. Explaining her move from first person to third, she says, “With each new book I write, I have some slightly Protestant work ethic thing about acquiring new skills and trying something different.”

Tuesday, March 10th, 2009

Laura Miller, inspired by Elaine Showalter’s A Jury of Her Peers, recently took up the “horribly fraught” question of whether women writers get their fair share of respect. Miller’s piece makes for an interesting companion to Jennifer Szalai’s review of Zoë Heller’s The Believers (above). On the one hand, Miller argues that women writers — with one or two notable exceptions — don’t feel as comfortable (or as entitled) as men do to attempt Great American Novels, the kind of all-you-can-eat buffets that Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon, Jonathan Franzen, and the late David Foster Wallace have produced. Szalai argues, in part, that some writers are simply more adept at smaller canvases, but that critics often overlook quality for quantity. It can be difficult to explain, without being dry, why a modestly plotted 250-page novel is affecting. It’s much easier to scream: It’s about war! And painkillers! And subdivisions! It’s 3,000 pages long!

I was struck by the American-British divide. Miller writes that British women are “perfectly at home with the capacious novel of ideas,” citing Iris Murdoch and Doris Lessing, and notes that “George Eliot practically invented the thing.” From Eliot to Zadie Smith, there’s a rich tradition of women writing “big” fiction in the UK. This is not to say America lacks strong women writers. But take a sample of them: Flannery O’Connor, Katherine Anne Porter, Marilynne Robinson, and Lorrie Moore. Three of those writers primarily produce (or produced) short stories. The fourth, Robinson, writes meticulous novels that are the opposite of bloated. It does feel like there’s an imbalance of scale. Miller makes a good case for why women wouldn’t have written much literature during America’s frontier days, so perhaps it’s just our relative youth skewing the overall picture.

This year’s Bookseller/Diagram Prize, for the year’s oddest book title,

This year’s Bookseller/Diagram Prize, for the year’s oddest book title,  This post is written by a guest, Levi Stahl, who blogs at

This post is written by a guest, Levi Stahl, who blogs at  If science fiction, which has gotten some play around here today, often requires thinking big — about the unknowable future, about human nature, about the broad consequences of catastrophe — then what’s the opposite of that? I submit that it may be writing about flies. Not giant, humanity-enslaving flies that have hatched from someone’s sinister lab (that must be the plot of some book, right?) but just, you know, flies. Here are two passages, from two great books —

If science fiction, which has gotten some play around here today, often requires thinking big — about the unknowable future, about human nature, about the broad consequences of catastrophe — then what’s the opposite of that? I submit that it may be writing about flies. Not giant, humanity-enslaving flies that have hatched from someone’s sinister lab (that must be the plot of some book, right?) but just, you know, flies. Here are two passages, from two great books —  After 48 games in four days, three straight days without basketball might be a harrowing prospect for some. To pass the time until Thursday night, maybe Seth Davis’ new book,

After 48 games in four days, three straight days without basketball might be a harrowing prospect for some. To pass the time until Thursday night, maybe Seth Davis’ new book,  Last night, I was browsing in

Last night, I was browsing in  Next week, I’ll be posting a full review of

Next week, I’ll be posting a full review of  Having had a fleeting experience with the book’s production, I can highly recommend Mr. America, Mark Adams’

Having had a fleeting experience with the book’s production, I can highly recommend Mr. America, Mark Adams’  I’m a fan of author’s letters, with some of my favorites including those by

I’m a fan of author’s letters, with some of my favorites including those by  A letter from Henry James to his brother William, dated November 23, 1905:

A letter from Henry James to his brother William, dated November 23, 1905: Just a brief round-up for anyone who’s missed the predictably and forcefully split critical reaction to Jonathan Littell’s

Just a brief round-up for anyone who’s missed the predictably and forcefully split critical reaction to Jonathan Littell’s