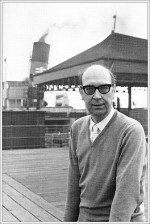

Philip Larkin wrote the following letter to his friend Norman Iles, who he had met when they were students together at Oxford, on Feb. 26, 1967:

Philip Larkin wrote the following letter to his friend Norman Iles, who he had met when they were students together at Oxford, on Feb. 26, 1967:

Dear Norman,

Thank you for your two letters: I received them with pleasure & read them with delight, & put them neatly together on one side — answering the buggers is another matter, though. My busy lazy life seems to have no time for letter writing. I liked the first letter a lot. You seem to have got your life taped, & not red-taped either. Don’t know how you do it.

As regards the second one, & your request for help in getting published, well, nothing I can say will make any publisher accept work he doesn’t think worth it. A year or so ago a woman whose six novels I much admire had her seventh rejected by her publisher: I charged in like a mixture of Sir Bedivere & Lloyd George to try to persuade Faber’s to take the seventh — played on the old-boy network like a harp. Nothing happened. So there you are. I’d be happy to read the poems, & give what advice I can, but in the end you’ve got to please the publisher, unless you’ve got money in the firm or are screwing his wife or something.

In a way you are lucky — you like your poems, & write a lot of them: perhaps you should produce them yourself, like Blake. I’m sure if Blake had sent me The Book of Ahania I’d have told him very much what I told you. Anyway, shoot them along. Don’t tell anybody else to do so, though. I get an increasing amount of such correspondence & haven’t really time to deal with much of it. [. . .]

I hope to get some new hifi stuff soon. Bachelors are always very keen on hifi — care more about the reproduction of their records than the reproduction of their species, haw haw. Not that I’ve many classical records — I keep putting it off until the evening of my days. Was that the 6 o’clock pips I heard just now?

Kind regards

Philip

Jonathan Franzen recently suggested that David Foster Wallace made things up in some of his most famous nonfiction pieces, including

Jonathan Franzen recently suggested that David Foster Wallace made things up in some of his most famous nonfiction pieces, including  The letter below was written by Stendhal to his sister Pauline on Oct. 29, 1808:

The letter below was written by Stendhal to his sister Pauline on Oct. 29, 1808: This week, the blog is featuring writers’ correspondence. The letter below was written by Eudora Welty to William Maxwell and his wife Emily in May 1963. It’s featured in

This week, the blog is featuring writers’ correspondence. The letter below was written by Eudora Welty to William Maxwell and his wife Emily in May 1963. It’s featured in  Each day this week, the blog will feature two letters. The one below was written by Harold Ross, the founder and editor of The New Yorker, to Orson Welles on Jan. 31, 1945. A selection of Ross’ correspondence was published as

Each day this week, the blog will feature two letters. The one below was written by Harold Ross, the founder and editor of The New Yorker, to Orson Welles on Jan. 31, 1945. A selection of Ross’ correspondence was published as  Each day this week, the blog will feature two letters. The one below was written by Anton Chekhov to publishing magnate Alexei Suvorin, his close friend, on Sept. 8, 1891:

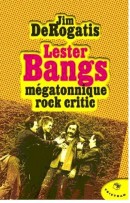

Each day this week, the blog will feature two letters. The one below was written by Anton Chekhov to publishing magnate Alexei Suvorin, his close friend, on Sept. 8, 1891: Cultural critic and Second Pass contributor Lisa Levy has launched the site

Cultural critic and Second Pass contributor Lisa Levy has launched the site  Emma Brockes’

Emma Brockes’