Wednesday, September 21st, 2011

Tom Bissell writes a lovely profile of Jim Harrison for Outside. Worth reading in full. Until you get the chance, here’s a brief excerpt that occurs after Harrison mentions the death of David Foster Wallace, who was a friend of Bissell’s:

Tom Bissell writes a lovely profile of Jim Harrison for Outside. Worth reading in full. Until you get the chance, here’s a brief excerpt that occurs after Harrison mentions the death of David Foster Wallace, who was a friend of Bissell’s:

Harrison brought up Jonathan Franzen’s much discussed New Yorker piece about Wallace, in which Franzen revealed that he could never get Wallace interested in his passion of bird watching. “This is interesting,” Harrison said. “Of the 12 or 13 suicides I’ve known, none of them had any interest in nature. In other words, they had no interest in what Rimbaud called ‘the other.’ The otherness, say, of nature.” They could not make, Harrison said, “that jump out of themselves.”

We were silent for a while. “You know,” Harrison said finally, “he loved his dogs for that last year, but he should’ve been having dogs for 30 years. Every day of the year, the first thing I do after breakfast is take the dogs for a walk. They absolutely depend on it. But it’s also what’s best for me.”

Friday, September 16th, 2011

At the New York Observer, I write about Paul La Farge’s new novel, Luminous Airplanes, which will be gradually expanded with additional text online to about three times the book’s length. I also spoke to La Farge about the project:

At the New York Observer, I write about Paul La Farge’s new novel, Luminous Airplanes, which will be gradually expanded with additional text online to about three times the book’s length. I also spoke to La Farge about the project:

He avoids calling his own work hypertext, preferring the term “immersive text.” The word “hypertext” has already fallen largely out of circulation (La Farge first conceived of this project in 1999), and the use of the form for literary purposes has been spotty at best. “With the exception of Geoff Ryman’s excellent 253, [hypertext fiction is] mostly pretty tough going,” La Farge said. “I think the early enthusiasm for the technology might have given writers a feeling of needing to do less writing work, because the form would carry the work. Whereas my sense is that the opposite is true: you have to pay as much attention to the writing of a hypertext as you would to the writing of a novel, or more attention, really, because novels produce a kind of natural engrossment, whereas online you’re always struggling to hold the reader’s attention.”

Thursday, September 15th, 2011

Nearly a decade ago, James Gavin published Deep in a Dream

Nearly a decade ago, James Gavin published Deep in a Dream , his biography of Chet Baker. Greil Marcus recently celebrated the fact that the book has finally arrived in paperback. Marcus says Gavin “seems to hold all of Baker’s music, piece by piece, song by song, phrase by phrase, every show, every recording, in his head, all at once,” and writes the musician’s life as “a long, long story of infinite shadings.” It’s also a sad, sad story:

, his biography of Chet Baker. Greil Marcus recently celebrated the fact that the book has finally arrived in paperback. Marcus says Gavin “seems to hold all of Baker’s music, piece by piece, song by song, phrase by phrase, every show, every recording, in his head, all at once,” and writes the musician’s life as “a long, long story of infinite shadings.” It’s also a sad, sad story:

Well before the end of his life, after he had lost most of his teeth in a drug-related beating in San Francisco, after he had turned into as charming, self-pitying, manipulative, professional a junkie as any in America or Europe, where for decades he made his living less as a musician than a legend, Baker wore the face of a lizard. In some photographs he barely looks human. But at the start he was, as so indelibly captured in William Claxton’s famous photographs, not merely beautiful, not merely a California golden boy — in the words of the television impresario and songwriter Steve Allen, someone who “started out as James Dean and ended up as Charles Manson.” He was gorgeous, he seemed touched by an odd light, and he did not, even then, look altogether human — but in a manner that was not repulsive but irresistibly alluring.

This also gives me a good excuse to share one of my favorite songs, which is Baker’s rendition of “I Get Along Without You Very Well.” Enjoy.

Thursday, September 15th, 2011

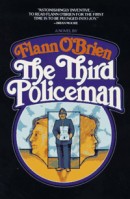

Oct. 5 marks the centenary of the birth of Irish novelist Flann O’Brien — the most famous pen name of those used by Brian O’Nolan — who died of cancer at age 54. Keith Hopper recently wrote an appreciation of O’Brien and his work for the New Statesman:

Oct. 5 marks the centenary of the birth of Irish novelist Flann O’Brien — the most famous pen name of those used by Brian O’Nolan — who died of cancer at age 54. Keith Hopper recently wrote an appreciation of O’Brien and his work for the New Statesman:

O’Nolan completed his second novel, The Third Policeman, in 1940. In its opening pages, a nameless narrator confesses that he has murdered an old man to get the money to publish a book about an eccentric philosopher. As a consequence of his actions, the narrator is transported to a hellish parallel universe, populated by killers and madmen and patrolled by three sinister policemen. The book is at once an existential whodunnit, an absurdist work of science fiction, a post-colonial allegory, and a dark, Menippean satire. In its philosophical scope and comic vision, it is funnier than Joyce and bleaker than Beckett, and is now considered one of the first — and finest — examples of postmodernist literature. [Publishing house] Longman, however, rejected it: “We realize the author’s ability but think that he should become less fantastic and in this novel he is more so.” Disheartened and embarrassed, O’Nolan pretended to have lost the manuscript, and The Third Policeman remained unpublished until 1967, a year after his death.

Tom Bissell writes a lovely profile of Jim Harrison for Outside. Worth reading in full. Until you get the chance, here’s a brief excerpt that occurs after Harrison mentions the death of David Foster Wallace, who was a friend of Bissell’s:

Tom Bissell writes a lovely profile of Jim Harrison for Outside. Worth reading in full. Until you get the chance, here’s a brief excerpt that occurs after Harrison mentions the death of David Foster Wallace, who was a friend of Bissell’s:

At the New York Observer,

At the New York Observer,  Nearly a decade ago, James Gavin published

Nearly a decade ago, James Gavin published  Oct. 5 marks the centenary of the birth of Irish novelist Flann O’Brien — the most famous pen name of those used by Brian O’Nolan — who died of cancer at age 54. Keith Hopper recently wrote an appreciation of O’Brien and his work

Oct. 5 marks the centenary of the birth of Irish novelist Flann O’Brien — the most famous pen name of those used by Brian O’Nolan — who died of cancer at age 54. Keith Hopper recently wrote an appreciation of O’Brien and his work